Goddy Uwa Osimen

BSc Political Science (Ambrose Alli, Ekpoma) MSc (Ibadan) MSc (IICSE University, USA) PhD (Ambrose Alli, Ekpoma)

Associate Professor, Department of Political Science and International Relations, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8294-6163

Mohadapwa Hunnoungu Wonosikou

BSc International Studies (Ahmadu Bello, Zaria) MSc (Covenant University, Ota)

MSc Student, Department of Political Science and International Relations, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-9254-9185

Theresa Nfam Odeigah

BA (Ilorin) MA (Ilorin) PhD (Kogi State)

Associate Professor, Department of History and International Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8786-4949

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the administration of Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation, and Discovery (CUCRID) for providing the framework for this article and publication assistance in the form of paper processing fees. The authors also acknowledge the reviewers for their insightful remarks.

Edition: AHRLJ Volume 25 No 2 2025

Pages: 627 - 658

Citation: GU Osimen, MH Wonosikou & TN Odeigah ‘National cybersecurity policy and citizens’ digital rights in Nigeria’ (2025) 25 African Human Rights Law Journal 627-658

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2025/v25n2a7

Download article in PDF

Summary

Nigeria’s cybersecurity framework, comprising policy instruments such as the National Cybersecurity Policy and Strategy 2021 and legislation, notably the Cybercrimes (Amendment) Act 2024, and the Nigeria Data Protection Act, 2023, aimed at strengthening national security, has prompted concerns that certain measures may undermine citizens’ digital rights. This article aims to examine the implications of the National Cybersecurity Policy and related legislation for citizens’ digital rights in Nigeria, including the rights to privacy, freedom of expression and internet access. Grounded in Buzan and Wæver’s securitisation theory, the article enquires as to whether calling something a security threat allows authorities to take extreme actions that limit citizens’ digital rights. Using mixed data collection methods, 15 respondents, made up of journalists, activists, lawyers and cybersecurity experts, were interviewed, and key policy texts were reviewed. Thematic analysis identified patterns linking policy framing to enforcement. Findings indicate increased state surveillance, frequent state-authorised takedowns of online content and chilling effects on public discourse. Implementation failures and infrastructural deficits, rather than explicit statutory bans, largely explain barriers to equitable internet access. The article contributes empirical evidence from a developing-country context to debates on the security-rights nexus and the operationalisation of securitisation. It recommends aligning national policy with international human-rights norms, establishing independent oversight, enhancing transparency, investing in infrastructure to reconcile security with rights, and informs pragmatic policy responses. By demonstrating how securitising moves translate into practice, the research emphasises the need for rights-respecting cybersecurity governance to protect democratic participation online.

Key words: citizens’ rights; cybercrime; cybersecurity; digital rights; National Cybersecurity Policy and Strategy; Nigeria; securitisation theory

1 Introduction

Historically, national security was narrowly conceived as military power, principally concerned with protecting lives and safeguarding public and private property.1 More recently, scholars have broadened this conception to cover a range of interconnected dimensions, including the economy, environment, information, food, health, politics and technology.2 This conceptualisation aligns with the Security Sector Reform Integrated Technical Guidance Notes of the United Nations (UN) which, while not offering a single, universally recognised definition of national security, emphasise the importance of comprehensive national security planning. Such planning addresses a spectrum of threats to the public good, covering defence, cyber threats, border security, organised crime, climate and health security and other emerging risks.3

As the world has changed, so too has the nature of security and the range of global threats. These dynamics have been shaped over time by political, social, technological and environmental forces.4 Security challenges have evolved, from medieval periods, when threats primarily arose from external aggression by neighbouring tribes or empires,5 to the post-Cold War era, which introduced novel risks such as terrorism, organised crime, sophisticated weaponry and cyber threats.6

In recent decades, cybersecurity has emerged as one of the most pressing concerns in international security: Cyberattacks increasingly target financial systems and critical infrastructure.7 The adoption of advanced technologies, including artificial intelligence and biotechnology, has further transformed the security landscape, raising complex issues of data protection, privacy and the technological dimensions of conflict.8 These global transformations in the security landscape have had significant implications for national contexts, particularly in countries experiencing rapid digital growth and technological adoption.9

In Nigeria, the rapid expansion of internet usage, with over 103 million users as of 2024, representing a penetration rate of 45,5 per cent,10 highlights the country’s significant digital growth. Awhefeada & Bernice observed that this expansion, however, has been accompanied by an increase in cyber threats, prompting government authorities to introduce targeted cybersecurity measures.11 Nigeria formally entered the digital security sphere in 2001 through the enactment and enforcement of mechanisms, such as the National Information Technology Policy (2001), aimed at safeguarding national cyberspace from criminal exploitation.12

Eze-Michael documents a pronounced rise in computer-related offences in Nigeria during the late 1990s and early 2000s. He reports that, over the period 2001 to 2022, Nigerian ‘419’ advance-fee scams accounted for 15,5 per cent of internet fraud complaints submitted to the United States (US) FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Centre, and that by 2003 Nigeria ranked third globally in fraudulent internet transactions, responsible for 4,81 per cent of such incidents.13 Oyedeji and others attribute this surge to the rapid diffusion of digital technologies, notably widespread Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) mobile uptake, increased availability of more capable personal computers, and a growing number of network providers, which together greatly expanded public access to the internet and created new opportunities for cyber-enabled crime.14

In December 2014, under President Goodluck Jonathan’s administration, the National Cybersecurity Policy was launched to consolidate national efforts against cybersecurity threats.15 The rapid growth of emerging technologies, accelerated by the 2019 coronavirus pandemic, soon revealed the need to update this policy to address the evolving nature of cyberspace.16 In February 2021, the National Cybersecurity Policy and Strategy (NCPS) was adopted, offering a comprehensive framework for managing the dynamic cybersecurity environment.17 Its implementation, however, has raised debates about potential impacts on citizens’ rights, particularly in relation to access to information, internet accessibility, freedom of expression and privacy.18

Building on concerns about policy implementation, between 2015 and 2023, Nigeria’s national cybersecurity measures were associated with multiple infringements of citizens’ rights. Notable examples include restrictions on freedom of expression during the #EndSARS protests through arrests and assaults on journalists, fines and regulatory pressure on broadcasters for airing protest footage and freezing of bank accounts used for fundraising.19 Instances of state-authorised digital surveillance that impinged on privacy, and measures such as the 2021 ban on Twitter, were actions that contributed to an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship.20 A 2018 survey found that 40 per cent of Nigerians felt unsafe expressing themselves online.21

While numerous studies have examined the technical and strategic aspects of cybersecurity in Nigeria,22 limited research has explored how the country’s cybersecurity strategy and policy affect citizens’ rights. This article addresses this gap by assessing the implications of national cybersecurity policies for rights such as freedom of expression, privacy, access to information and access to the internet between 2015 and 2024, to offer recommendations for a more rights-sensitive approach to cybersecurity governance.

The main objective of the article is to examine the implications of Nigeria’s National Cybersecurity Policy for citizens’ digital rights. It enquires into the way in which the NCPS has influenced citizens’ digital rights between 2015 and 2024. Grounded in Buzan and Wæver’s securitisation theory, the research adopts a case study design and a mixed-methods approach, drawing primarily on semi-structured interviews and documentary sources (scholarly literature, policy papers and official texts). Qualitative data were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic framework.23 Methodological triangulation was employed to enhance credibility by systematically comparing and integrating interview-derived themes with evidence from secondary sources.

2 Materials and methods

This article investigates the implications of Nigeria’s Cybersecurity Policy for citizens’ rights between 2015 and 2024, a period spanning the policy’s adoption, operationalisation and its 2021 revision. The timeframe also encompasses critical national events such as the #EndSARS movement in 2020 that tested the state’s commitment to protecting digital rights. Adopting a case study design enabled a contextual and process-oriented analysis of the NCPS within its real-life socio-political setting.

Primary and secondary data sources were integrated using a mixed-methods approach. Primary data were collected via in-depth interviews by way of a purposive sample of 15 participants. The interviewees were stakeholders central to cybersecurity governance and human rights advocacy in Nigeria, including activists, investigative journalists, lawyers and cybersecurity experts with direct experience of the impacts of NCPS on civil liberties. Secondary data comprised peer-reviewed literature, official policy documents (including NCPS iterations), legislative instruments, institutional reports and reputable media accounts. Secondary materials were used both to situate the empirical findings in the extant literature and to provide documentary corroboration of interview evidence.

Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis in accordance with Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework. The six-phase thematic analysis is a systematic, transparent approach to identifying, analysing and reporting patterns in qualitative data. The method advances through interlinked stages, beginning with close familiarisation with transcripts, generating initial codes, searching for and collating codes into candidate themes, iteratively reviewing and refining those themes, defining and naming the final themes, and culminating in the production of a coherent analytic report. This framework was selected because it supports an inductive, data-driven approach, emphasises the researcher’s reflexive role, and requires clear documentation of coding decisions, thereby enhancing the credibility and auditability of interview-based findings.24

Using Braun and Clarke’s framework, an inductive, manual coding strategy was employed: Transcripts were read repeatedly to achieve familiarity, initial codes were generated from the data, related codes were clustered into candidate themes, and themes were iteratively reviewed and refined until they demonstrated internal coherence and analytic distinction. All coding was conducted to maintain consistency and close engagement with the dataset. To enhance credibility and validity, methodological triangulation was applied by systematically comparing and integrating interview-derived themes with evidence from the secondary sources, and coding decisions were documented to ensure analytic transparency.

This research was reviewed and approved by the Covenant Health Research Ethics Committee (CHREC), Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria.25 Approval was granted on 30 May 2025 and is valid until 29 May 2026. All procedures performed in this article complied with institutional guidelines and the National Code for Health Research Ethics.

3 Review of literature

3.1 Cybersecurity strategies and policies

The concept of cybersecurity originated in the US, where it gained prominence during the twentieth century before gradually diffusing to other parts of the world. As a result, scholarly and professional discourse on cybersecurity has been heavily influenced by American perspectives.26 The rapid advancement of information and communication technologies (ICT) has since produced varied and multidimensional interpretations of the term, with definitions shaped by the priorities and contexts of different stakeholders.27 In this regard, Molwantwa’s observation that cybersecurity is best understood through the distinct lenses of diverse actors and sectors remains particularly relevant.28

Akpan conceptualises cybersecurity as the mechanisms employed to protect computing systems.29 Building on this, the widely cited definition of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) frames cybersecurity as a comprehensive framework of tools, protocols, practices, safeguards, strategies and technologies intended to protect cyberspace and the assets of users and organisations. These assets encompass interconnected devices, personnel, infrastructure, applications and services, telecommunications systems, and all information transmitted or stored within cyberspace.30

Alabi describes cybersecurity in terms of preserving the confidentiality, integrity and availability of information systems, data and networks in the face of malicious and accidental threats.31 Both definitions converge on the view that cybersecurity is a proactive, systems-level endeavour designed to prevent, detect and mitigate cybercrime. This perspective further implies that cybersecurity measures must protect the full ICT ecosystem of the state, including organisational resources, citizens and Critical National Information Infrastructure (CNII), rather than merely addressing isolated technological faults.

Haddad and Binder argue that cybersecurity rests on systematic, scientific processes and measures; the coordinated plans and structured approaches designed to secure cyberspace are commonly termed cybersecurity strategies.32 Over recent decades, states have embedded these strategies within broader national-security architectures, recognising their role in managing digital risks.33 The ITU’s 2024 Global Cybersecurity Index confirms this trend: By 2024, 132 countries had adopted a National Cybersecurity Strategy (NCS), up from 107 in 2020, underscoring the growing importance of NCSs as instruments for government coordination and response to cyber threats.34

The regulation of cyberspace through legal frameworks is well established, yet debates persist between cyberlibertarians, who advocate minimal state interference, and state-centric scholars, who argue that national and international laws are essential for cyber governance.35 This ideological divide underpins the evolution of international cyber law. In recent decades, cyberspace has shifted from minimal regulation to governance through comprehensive cybersecurity and cybercrime policies aimed at strengthening national security and mitigating risks.36 While most states shape responses according to domestic priorities, other countries, such as Russia, pursue opaque strategies, illustrating divergent governance models with varied implications for transparency and rights protection.37

Lanzendorfer notes that numerous multilateral agreements and cooperative mechanisms have emerged to address cybersecurity threats collectively, alongside several ongoing initiatives.38 Prominent among these is the UN Group of Governmental Experts (UNGGE) which, under the UN General Assembly, develops normative guidance for responsible state behaviour in cyberspace. Complementing the GGE, the UN’s Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security provides an inclusive forum for deliberation on norms, legal frameworks and capacity building. Established by UN Resolution A/RES/75/240 (November 2020), the OEWG commenced work in 2021 and was tasked with reporting its conclusions to the General Assembly in 2025.39

Nte and others note that national cybersecurity strategies are typically shaped by a country’s threat typology, its strategic vision, the measures adopted to address vulnerabilities, and the policies enacted to operationalise those measures.40 For instance, in response to ransomware-driven losses estimated at US $3 billion, Australia launched the Australian Cyber Security Strategy 2023-2030, a comprehensive programme under the Albanese government that seeks to position Australia as an international model in cybersecurity by 2030.41 Similarly, Finland’s Cyber Security Strategy 2024-2035 articulates a forward-looking vision centred on securing vital cyber functions and enhancing national preparedness; it is organised around four pillars: competence, technology and research; preparedness; cooperation; and response and countermeasures.42

South Africa has emerged as an African leader in national cybersecurity. Bote critically examined South Africa’s National Cybersecurity Policy Framework (NCPF 2015), observing that it is organised around political commitment, adapted organisational structures, proactive and reactive measures, reduction of criminal opportunities, and education and awareness.43 Bote argues that the NCPF operates largely as a strategic framework rather than a prescriptive policy, serving principally as a roadmap for agency-level policy development.44

A common feature of high-performing national strategies, exemplified by South Africa, Australia and Finland, is an explicit emphasis on cyber-incident management and proactive resilience building, reflecting the recognition that technological change is permanent and requires forward-looking responses. The ITU’s Global Cybersecurity Index (2024) corroborates these trends: 46 countries attained Tier-1 status in 2024, signalling a strong institutional commitment to cybersecurity.45

Although continental instruments exist, Greenleaf and Cottier argue that Africa lacks a distinct, regionally rooted approach to cybersecurity and data protection law that reflects communitarian values and African human rights discourse.46 By contrast, sub-regional mechanisms, most notably the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), have taken more concrete steps towards legal harmonisation. Orji shows that ECOWAS’s Cybercrime Directive (C/DIR.1/08/11), adopted in August 2011, embodies these efforts by obliging member states to achieve common objectives while permitting domestic flexibility in implementation.47 This approach is grounded in the ECOWAS Treaty, which requires coordination and alignment of national policies across communications, technology and legal domains.48 Thus, although pan-African frameworks remain embryonic, ECOWAS provides a practical model for regional cooperation that balances harmonisation with respect for national contexts.

3.2 Citizens’ digital rights

The accelerating interconnectivity of the modern world, and the transnational challenges it generates, have prompted scholars, practitioners and activists to reconceptualise citizenship so as to better address contemporary global problems.49 This reconceptualisation raises a central question for the digital age: Who qualifies as a citizen when political, social and economic participation increasingly occurs online?

Aristotle’s classical account remains a useful point of departure. In Politics, he defines a citizen in relation to governance: a citizen is someone who takes part in deliberation and public decision-making and retains the eligibility to rule or be ruled, irrespective of holding office.50 While Aristotle’s focus on civic participation and responsibility endures, it is now being reinterpreted for a world where membership, agency and political voice can transcend territorial boundaries.

Mravcová advances this reinterpretation by framing citizenship within the ‘global village’ created by technological advancement. She conceptualises citizenship as participation in a global civic sphere, with environmental citizenship serving as a paradigmatic example that transcends national borders, regional blocs and continents, promoting a shared sense of responsibility.51 This broadened view recognises that individuals retain strong national identities while also belonging to a wider community collectively accountable for addressing transnational challenges. Such a framework is equally relevant to the digital domain, where rights and responsibilities increasingly extend beyond territorial jurisdictions, reshaping the meaning and scope of citizenship in the twenty-first century.

Although the concepts of human rights and citizens’ rights are often used interchangeably, they are distinct in scope and application. Rutte observes that while human rights are universally recognised, certain rights remain contingent upon citizenship status.52 Similarly, Bartels and Schramade emphasise that the human rights framework is primarily directed at the state, imposing obligations on governments to respect, protect and fulfil the rights of their citizenry.53 This highlights the interdependence of the two concepts, as each informs and shapes the other. Whereas human rights apply universally to all individuals regardless of sex, race or nationality,54 citizens’ rights are conferred exclusively upon the legal members of a state and are safeguarded by its constitution.55

Duarte draws on Marshall’s seminal work Citizenship and social class which, despite its mid-twentieth century origins, continues to provide valuable insights into the evolution of citizens’ rights amid changing social, economic and political contexts.56 Marshall’s framework distinguishes three core components of citizenship in democratic societies: civil rights, encompassing individual freedoms such as liberty and justice; political rights, relating to participation in governance; and social rights, which guarantee access to welfare and socio-economic security.

Caldwell underscores the growing need to extend rights into the digital sphere, mirroring those recognised offline.57 While the UN has sought to uphold offline human rights in the online environment, such efforts largely take the form of soft law, non-binding agreements that lack the enforceability of hard law.58 Consequently, internet access is increasingly framed as a supplementary fundamental right.59 In this regard, the Human Rights Council has reaffirmed that the rights individuals enjoy offline must be equally protected online. As cyberspace becomes a primary arena for the exercise and infringement of rights, there is an increasing expectation that public institutions responsible for safeguarding fundamental freedoms must actively protect the rights of digital natives.60

The rights enjoyed by citizens in the online domain are commonly referred to as digital rights,61 although Pangrazio and Sefton-Green propose the term ‘rights in the digital age’ as more linguistically precise.62 Regardless of terminology, digital rights are now firmly embedded in the discourse on fundamental freedoms. According to Reventlow,63 these rights encompass the legal entitlements that enable individuals to access, create and share digital content, participate in virtual environments and engage with online communities through technology-driven platforms.

Kothari defines digital rights as an extension of offline fundamental rights, protected and advanced through international laws and conventions.64 Traditionally, human rights frameworks have centred on offline freedoms within territorial nation-state systems, a view echoed by Guberek and Silva,65 who note that institutions safeguarding these rights are geographically bound. Recent international initiatives, however, are reshaping these frameworks to address emerging technologies and evolving digital norms, highlighting the need to protect specific rights in the context of cybersecurity. Some of these existing rights that require protection in relation to cybersecurity include the following:

3.1.1 Citizens’ rights to access the internet

Bieliakov and others position internet access as a fundamental prerequisite for realising universal basic rights in the digital sphere. From a human rights perspective, this aligns with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and related instruments, which imply that access to communication channels is integral to freedoms of expression, association and participation. According to this view, restricting access impairs the effective exercise of these rights.66

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) recognises the internet as a vital source of knowledge, enabling civic engagement and freedom of expression while presenting distinct challenges for rights protection.67 Estrada further argues that internet access should be recognised as a social right, comparable to education and health care, which states have a duty to provide.68 This position has gained policy traction: In 2010 the UN urged universal internet access; in 2011 the Council of Europe recommended integrating it into national policies; and, as early as 2008, New Zealand’s Minister of Justice likened it to essential utilities such as water and electricity.69

3.2.2 Citizens’ rights to access information

The right to access information is widely recognised as a fundamental human right, grounded in international instruments such as article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Universal Declaration) and ICCPR. Historically, freedom of information laws have been instrumental in enabling citizens to hold governments accountable and to challenge authoritarian practices, with adoption now spanning jurisdictions from Albania to Zimbabwe.70 Resistance to such laws has often reflected entrenched governance cultures; for example, in the United Kingdom, critics long argued that freedom of information was incompatible with its political system.

In the digital era, as Singh notes, unprecedented technological capacity has expanded global access to knowledge, while simultaneously creating new challenges to information integrity and security.71 A comprehensive understanding of the right to information encompasses both the right to inform, publicly disseminating ideas without censorship, and the right to be informed, obtaining relevant, diverse and accurate information.72

International and regional frameworks have sought to safeguard this right. UNESCO’s Internet Universality Indicators 2018 promote open access policies and cross-border digital inclusion, while the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa, 2019 mandates African states to adopt robust legal safeguards, especially in the digital sphere.73 Nationally, Nigeria’s FOI Act (2011) facilitates public access to government records, enhancing transparency and accountability.74 Nonetheless, barriers persist. Singh identifies digital rights management (DRM) as a key impediment, limiting knowledge accessibility under the guise of protecting intellectual property.75

3.2.3 Citizens’ rights to freedom of expression

Article 19 of ICCPR guarantees the right to freedom of expression, encompassing the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers. General Comment 34 provides an authoritative interpretation, confirming that these protections apply equally to offline and online communication, including digital and internet-based platforms.76

Kettemann conceptualises freedom of expression as the right to access, share and exchange information and ideas across borders, with the internet serving as a central enabler.77 However, the scope of this right is under strain globally. The Global Expression Report 2024 by ARTICLE 19, which assesses 161 countries using 25 indicators, reveals a marked deterioration: The ratio of individuals inhabiting countries recognised as ‘in crisis’ for free expression rose from 34 per cent in 2022 to 53 per cent in 2023, meaning that approximately 4,2 billion people now reside in contexts where open expression is curtailed.

Freedom of expression in the digital domain also entails responsibilities. International law prohibits harmful forms of speech, such as incitement to violence, glorification of terrorism, promotion of genocide and sexual exploitation of children, and obliges states to criminalise such acts.78 Under article 19(3) of ICCPR, restrictions are permissible only if they meet a cumulative three-part test: They must be provided by law, pursue a legitimate aim (such as those set out in article 19(3) of ICCPR or article 10(2) of the European Convention on Human Rights) and be necessary and proportionate to that aim. This framework reflects the balance between safeguarding democratic discourse and preventing harm in digital spaces.

3.2.4 Citizens’ rights to privacy

Technological advancements and evolving socio-economic and political contexts have necessitated the recognition of new rights, with common law adapting to protect emerging societal interests. Among these, the right to privacy has gained prominence; as Pfisterer observes, ‘privacy is on the rise’.79 Warren and Brandeis famously defined privacy as the ‘right to be let alone’, emphasising non-interference, an idea shaped by technological innovations and shifting commercial practices.80

Over time, scholars have refined this concept. Bygrave distils privacy into key elements: non-interference; restricted access; control over personal information; and the safeguarding of sensitive personal attributes.81 Prosser identifies four core dimensions: intrusion into private affairs; public disclosure of personal information; misrepresentation or false portrayal; and unauthorised use of a person’s identity for another’s gain.82

Despite increasing recognition, global privacy and data protection rights remain limited in practice. Solove identifies three key challenges: the lack of enforceability for many privacy rights at the individual level; reliance on ‘privacy self-management’, which assumes individuals have the capacity to make informed data decisions, an assumption often unrealistic; and the interdependent nature of privacy, whereby individual choices can have wider societal implications.83

Taken together, the rights to internet access, access to information, freedom of expression and privacy form a core cluster of digital rights. However, as studies reveal, cybersecurity laws and policies can both enable and constrain these rights in online spaces, making their balance central to contemporary governance debates.

3.3 Nigeria’s digital landscape

Nigeria’s cyberspace has become central to economic and social life, with widespread integration of online platforms into business and public services driving concomitant increases in cybercrime.84 Consequently, cybersecurity has risen to the top of the national security agenda. The federal government has actively engaged in international cybersecurity fora and partnerships, securing membership of bodies such as the International Multilateral Partnership Against Cyber Threat (IMPACT), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and the International Criminal Police Organisation (Interpol), and pursuing participation in specialised networks, including the Forum of Incidents Response and Security Teams (FIRST) and the Global Prosecutors E-Crime Network (GPEN). Nigeria has also pursued multilateral and bilateral instruments aimed at strengthening cross-border cooperation on cybercrime.85

At the national level, the presidency, through the Office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA), has assumed a coordinating role. In 2014 ONSA issued the National Cyber Security Policy and Strategy, a six-year coordination plan that established the country’s first comprehensive framework for protecting digital infrastructure. The policy emphasises multi-stakeholder engagement, international cooperation and public-private partnerships as pillars of national cybersecurity.86 The rapid shift to online activity during the COVID-19 pandemic further expanded Nigeria’s digital footprint and, with it, the complexity and scale of cyber threats.

As the threat landscape evolved, policy makers moved to review the 2014 strategy. This produced NCPS 2021, which realigns Nigeria’s cybersecurity priorities to address emerging and persistent threats and to advance national security and defence objectives. The NCPS articulates a vision of a resilient, safe, trusted and vibrant digital environment that protects national assets and interests, promotes peaceful interaction and fosters proactive citizen engagement to support national prosperity.87

Both the 2014 and 2021 NCPS documents identify recurring threats that undermine development and national security: cybercrime; cyber espionage; cyber-conflict; cyber-terrorism; child online abuse and exploitation; election interference; pandemic-related cyber threats; and online gender-based exploitation.88 The strategy proposes a multi-pronged implementation approach organised around its core pillars, which the policy describes as fundamental to realising the NCPS objectives. These include strengthening cybersecurity governance and coordination; fostering protection of critical national information infrastructure; enhancing cybersecurity incident management; strengthening the legal and regulatory framework; enhancing cyber-defence capability; promoting a thriving digital economy; assurance, monitoring and evaluation; and enhancing international cooperation.89 These pillars form the architecture for multi-stakeholder engagement, public-private partnerships and international cooperation that the policy emphasises.

As Nigeria’s digital footprint has expanded, the country has experienced a string of high-impact cyber incidents that underscore both the scale of the threat and the urgency of robust incident management. The Sophos State of Ransomware 2022 reports a sharp rise in ransomware targeting Nigerian organisations: Incidents reported rose from 22 per cent in 2020 to 71 per cent in 2021, and 43 per cent of Nigerian businesses reported an attack in the previous year compared with a global average of 27 per cent.90 The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) publicly disclosed the compromise of its official Twitter account on 8 June 2022. Earlier, in 2020, media reports alleged a cyberattack on the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) attributed to the collective known as ‘Anonymous’. Moreover, Kaspersky recorded a 147 per cent increase in detections of password theft malware (Trojan-PSW) in Nigeria in 2022 versus 2021.91 Collectively, these incidents illustrate how threat actors exploit rapid digital adoption and highlight critical vulnerabilities in organisational defences and national incident response capacity.

Incidents and the quality of incident management together define Nigeria’s cybersecurity landscape and emphasise the need for a forward-looking strategy aligned with emerging technological trends. From a civic space perspective, Agwuegbo argues that some cybersecurity measures have contributed to a shrinking online public sphere in Nigeria, reducing institutional responsiveness to citizen demands and exacerbating tensions between security imperatives and digital rights.92

4 Securitisation theory: Conceptual foundations

This article is anchored in securitisation theory, as developed by Buzan and others, which offers a constructivist lens for understanding how issues are transformed into security problems through discourse and practice. Rather than treating security as an objective condition,93 the theory argues that political actors produce perceptions of existential threat by declaring a condition or phenomenon to jeopardise a valued referent object, and when such speech acts persuade a relevant audience, they legitimise extraordinary measures beyond ordinary politics.94

Central to this formulation are three interrelated dynamics: the performative power of speech acts that frame an issue as an existential danger; the consequent logic of exception that removes that issue from routine political contestation and justifies exceptional legal, administrative or technical responses; and the actor-audience relation in which the success of securitisation depends on the acceptance or validation of those claims by legitimising bodies such as parliament, the media or the public.95 The theory has invited normative critique. Scholars caution that it lacks clear criteria for when securitisation is justified and warn that analysts themselves may inadvertently reproduce securitising language, thus necessitating reflexivity in application.96

Applied to cybersecurity in Nigeria (2015 to 2023), securitisation theory helps explain how state actors frame phenomena such as cybercrime, misinformation and data breaches as existential threats, how particular audiences come to validate these framings, which exceptional measures are authorised in consequence and, crucially, how those measures impinge on citizens’ rights including privacy, expression, access to information and the internet.

5 Findings and discussion: Cybersecurity policy – Mechanisms and implications for citizens’ rights

5.1 Cybersecurity policies as a tool for silencing dissent

Nigeria’s 2021 NCPS establishes a strategic framework for the coordinated management of the country’s cyberspace, supported by a suite of complementary programmes and ICT reforms introduced in recent years. Key initiatives include the National Broadband Plan (2020-2025), the Economic Sustainability Plan (2020), administrative reforms such as the Treasury Single Account (TSA) and the Bank Verification Number (BVN), alongside data-protection and cybercrime instruments, including the National Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) and the Cybercrimes Act.97 Collectively, these measures seek to curb cybercrime and strengthen the digital environment, but critics argue they have also expanded state control over online expression.

Adegoke contends that authorities have criminalised digital speech by extending traditional offences to online conduct or enacting provisions that target internet-based communication, a trend that appears at odds with Nigeria’s international human rights commitments.98 Empirical work supports these concerns: Salisu and others report that cybersecurity policies significantly influence tertiary students’ online behaviour and safety practices in North-Eastern Nigeria.99 Observers such as Paradigm Initiative note a progressive contraction of civic space online, evidenced by the Cybercrimes Act, the stalled Digital Rights and Freedoms Bill, proposed hate speech and social media laws, and the draft Code of Practice for Internet Intermediaries,100 while Anyogu and Nwachukwu warn that labels of ‘hate speech’ are sometimes applied to legitimate political criticism, resulting in disproportionate curbs on freedom of expression.101

Obiora and others contend that the Cybercrimes Act 2015 has been misapplied to criminalise online discourse, resulting in the detention of journalists, critics and digital dissidents, thereby undermining citizens’ freedom of expression.102 Corroborating this, a key informant lawyer observed that cybersecurity policies have at times been selectively enforced, effectively privileging powerful actors and ensuring that measures such as enhanced cybersecurity responses are mobilised most vigorously when high status victims are involved, undermining the policy’s stated aim of universal protection.103

Adegoke documents the hostile environment faced by journalists and human rights defenders, intimidation, harassment and incarceration, and the government’s suspension of Twitter provides a striking instance of online speech being curtailed.104 A key informant reported concrete examples of this pattern: law suits, arrests and short-term detentions of journalists and bloggers for truthful reporting; the repeated imprisonment of the activist Very Dark Man; a youth corps member compelled to apologise after criticising the President; and serving military personnel court-martialled for public commentary.105 Taken together, these accounts suggest an inconsistent application of Nigeria’s cybersecurity framework, one that, despite formal commitments to international digital rights norms, has frequently had the effect of contracting civic space and chilling legitimate political expression.

Akintayo argues that cybersecurity legislation has been deployed instrumentally to intimidate and suppress journalists and activists, thereby curtailing freedom of expression and eroding civic space: The sweeping powers conferred by the Cybercrimes Act permit profiling, isolation and other measures that deter dissent and foster self-censorship.106 At the same time, Eze and Eze observe that the proliferation of smartphones and the rise of citizen journalism have expanded real-time reporting and diversified voices in the public sphere, even as state and non-state actors routinely subject journalists and media organisations to digital surveillance that endangers independent reporting.107

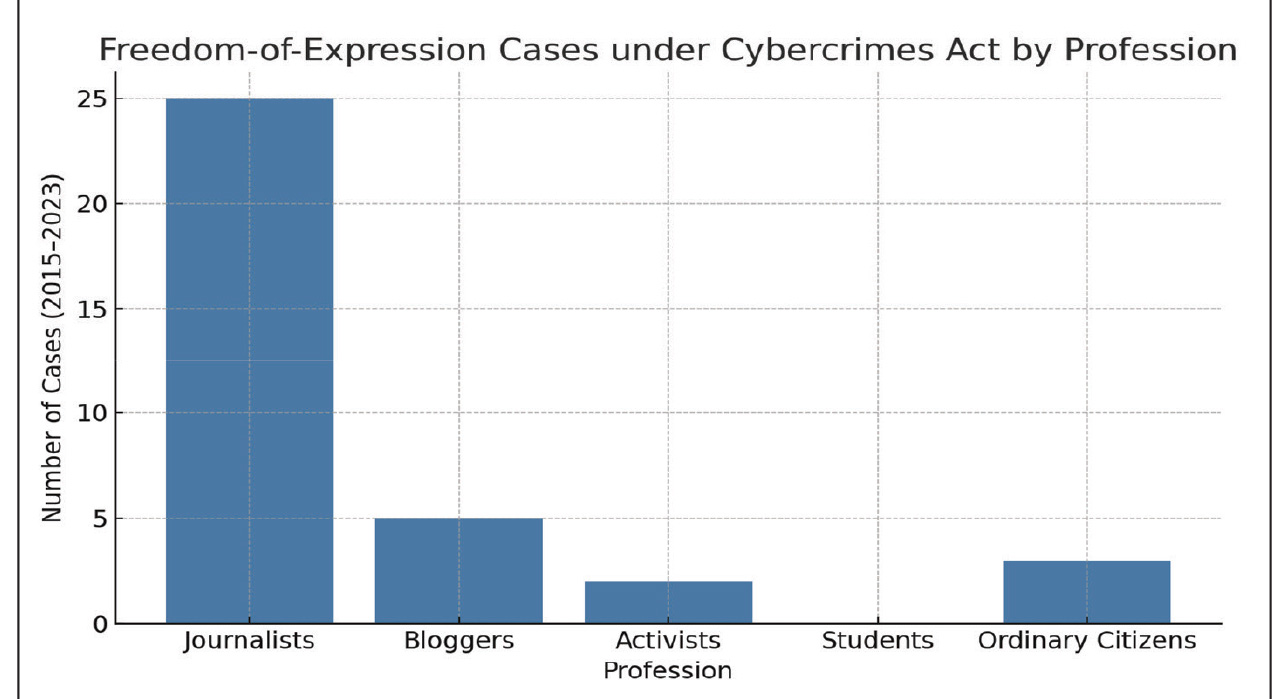

These dynamics are reflected in prosecution patterns: Figure 1 summarises prosecutions under the Cybercrimes Act (2015-2023) by professional profile and demonstrates that journalists constitute the largest group targeted (25 cases; 71 per cent); followed by bloggers (5 cases; 14 per cent); ordinary citizens (3 cases; 9 per cent); and activists (2 cases; 6 per cent); no students faced federal charges. This distribution demonstrates that NCPS-related enforcement disproportionately affects those engaged in reporting and commentary, emphasising the broader finding that cybercrime provisions are frequently deployed to discourage critical speech rather than to remediate genuine cybercrime alone.

Figure 1: A bar chart illustrating the distribution of freedom of expression cases prosecuted under the Cybercrimes Act (2015-2023) by profession

Source: Author’s Computation (2025) based on CPJ, EFCC, and Freedom House data

Source: Author’s Computation (2025) based on CPJ, EFCC, and Freedom House dataAbdulrasaq offers a judicial perspective on the effects of cybersecurity legislation on freedom of expression by analysing Solomon Okedara v Attorney-General of the Federation (Federal High Court, per Buba J), in which the Court rejected the appellant’s contention that section 24 of the Cybercrimes Act was so vague, overbroad and ambiguous that it imperilled the constitutional right to free expression under section 39 and fell outside the permissible limitations of section 45.108 Abdulrasaq further notes that many scholars and practitioners dispute the application of section 24 (as amended in 2024) to curtail press freedoms, arguing that neither the media nor individual journalists and bloggers should be unduly constrained from publishing lawful information.109

5.2 Expansion of state surveillance powers and erosion of privacy safeguards

Adegoke rightly identifies privacy as one of the most pressing human rights issues of our time, a boundary that protects individuals’ communications, personally identifiable information and private spaces from intrusive scrutiny. In Nigeria this protection is constitutionally recognised. Section 37 of the 1999 Constitution (as amended) affirms the privacy of the home, correspondence and telecommunications, yet contemporary policy and statutory instruments create wide avenues for state intrusion.110 Effoduh and Odeh assert that the NCPS and related instruments acknowledge the need for data protection laws such as the NDPR, but these frameworks operate alongside statutes that grant authorities broad interception and access powers, often with weak oversight and carve-outs that undermine protective intent.111

Although regional law expressly demands narrow, supervised processing of personal data, Nigeria’s pattern of intensive monitoring undermines those safeguards. The African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (Malabo Convention) requires that any processing of personal data be grounded in law, limited in purpose, scope and duration, and subject to independent oversight. Article 13, in particular, makes it clear that processing must rest on consent or another lawful basis and be confined to specified purposes.112 Nigeria’s National Cybersecurity Policy formally endorses the same balancing logic, affirming privacy as the default, citizens ‘shall be allowed to communicate without interception’, and stating that the right to privacy may be curtailed only on reasonable suspicion of crime or national security threats.113

In practice, however, these policy commitments have been unevenly translated into statutory safeguards. The Cybercrimes Act and its implementing practices provide for judicial warrants for interception in principle, and the NDPA establishes data protection rights and an independent regulator. Yet, statutory provisions and operational rules also permit broad data preservation obligations and routine disclosure demands on service providers that are not always subject to robust, independent review.114 The result is a persistent gap between the NCPS’s de jure emphasis on minimisation, transparency and oversight, and the de facto environment in which expansive retention and expedited disclosure powers can be exercised with limited procedural checks. This divergence weakens the protective architecture Malabo envisages and exposes citizens to risks of disproportionate intrusion and inadequate remedies.

A key informant observed that, while Nigeria has the requisite frameworks on paper, enforcement is inconsistent, legal provisions are frequently vague, and surveillance practices lack transparency, resulting in inadequate protection for citizens’ privacy.115 In practice, this tension means that measures introduced in the name of national cybersecurity can nullify safeguards by permitting intrusive collection, retention, or interception of personal data without independent oversight. Framed through securitisation theory, such expansions of surveillance can be understood as outcomes of threat framing: When cyber risks are presented as existential, exceptional powers become easier to justify, with significant implications for the balance between security and civil liberties.

Owuamanam argues that abuses of fundamental rights under Nigeria’s cybersecurity framework extend well beyond restrictions on expression to encompass incursions on privacy, noting that statutory authorisations for intercepting electronic communications lack adequate checks and balances, thereby exposing citizens to arbitrary surveillance.116 Indeed, Nigeria’s surveillance regime is principally governed by the Terrorism (Prevention) Act 2011 and the Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention, etc) (Amendment) Act 2024.117 Obiora, Chiamogu and Chiamogu report that traditional media actors, journalists, reporters and news organisations operate under intensive monitoring and regulation by state agencies that frequently treat press output as a potential national security risk.118

Compounding this dynamic, section 30(1) of the NDPA permits disclosure of personal data by controllers and processors where such disclosure is deemed necessary in the public interest. Read alongside section 45 of the 1999 Constitution, such provisions can be invoked to justify intrusions permitted under the Cybercrimes Act. However, key terms such as ‘reasonable grounds’, ‘public safety’ and ‘public interest’ are indeterminate and susceptible to expansive interpretation, which risks furnishing over-zealous authorities with legal pretexts to erode constitutionally guaranteed rights.119

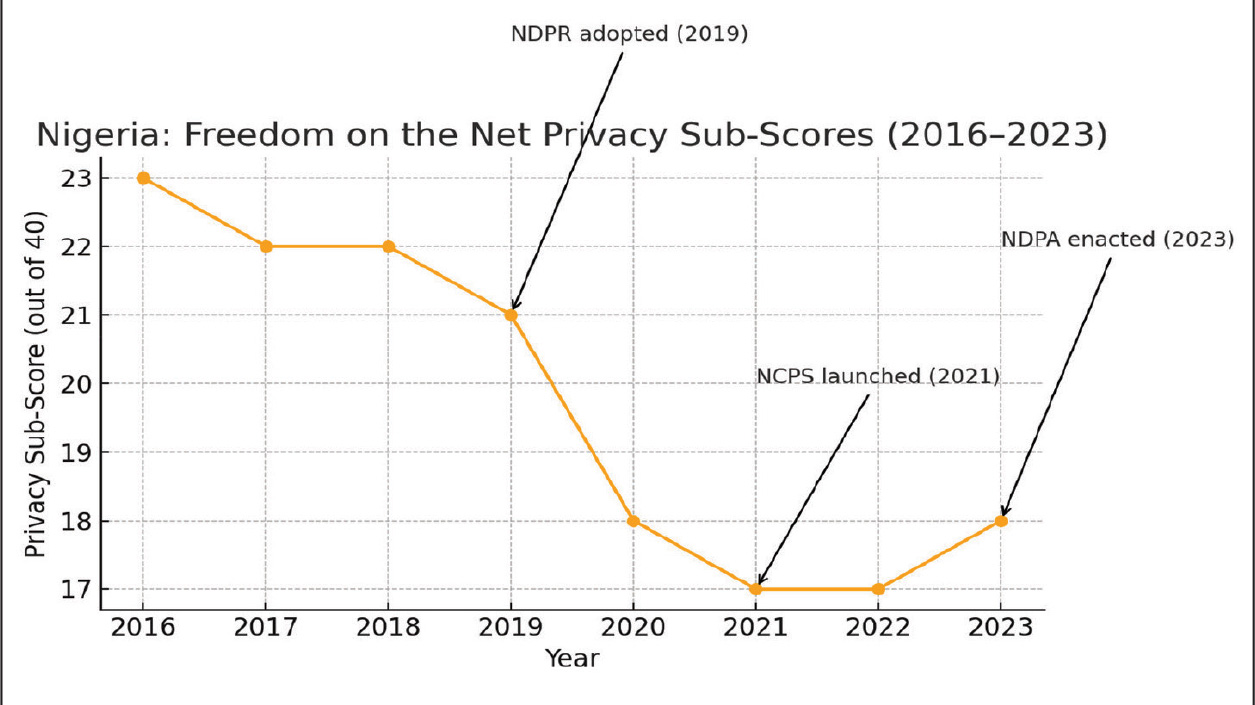

Nigeria’s privacy protections remain fragile in practice despite the proliferation of regulatory instruments. Nte and others note that the country still has considerable ground to cover before citizens can be regarded as adequately shielded from privacy infringements,120 a trend reflected in the Freedom on the Net privacy sub-scores (Figure 2). According to a key informant, although the NCPS and the NDPR set out robust data protection standards, enforcement is weak in practice: Law enforcement agencies reportedly conduct warrantless searches of mobile phones and banking applications, contravening policy intent and substantially undermining individuals’ privacy.

Figure 2: Nigeria: Freedom on the Net privacy sub-scores (2016-2023), annotated with key policy milestones

Source: Author’s computation (2025) based on Freedom House, Freedom on the Net Reports (2016-2023)

Nigeria’s privacy sub-scores, as reported in Freedom on the Net (Freedom House, 2016-2023) shown in Figure 2, reveal a downward trajectory between 2016 and 2021, indicating that early cybersecurity and data protection initiatives struggled to translate into effective legal safeguards. The post-NCPS period (2021-2022) reflects stagnation, with only a modest improvement following the enactment of the NDPA in 2023. This trajectory suggests that, despite the introduction of instruments such as the NDPR, NCPS and NDPA, their impact on strengthening citizens’ privacy rights has been limited and incremental. The pattern aligns with wider evidence of weak enforcement, ambiguous statutory exceptions and restricted institutional oversight, which collectively undermine the effectiveness of Nigeria’s privacy framework.

5.3 Instrumentalisation of cybersecurity policy for digital censorship

Andre argues that the freedom to access information constitutes a fundamental entitlement and underpins all other freedoms, often termed an enabling right because it is indispensable for fulfilling broader human rights, enabling individuals to make informed decisions and contribute constructively to societal progress.121 Although Nigeria’s FOIA was eventually enacted in 2011, the campaign for such legislation dates back to 1993, making Nigeria the ninth African nation to adopt such a law, which grants citizens the right to request and obtain information held by public authorities, agencies and institutions.

Abdulrasaq similarly contends that access to information is an inviolable human right, firmly established by section 39 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (CFRN), which guarantees every individual the right to receive information. However, the Cybercrimes Act 2015 (as amended in 2024) significantly curtails this entitlement, with section 6 expressly prohibiting any person from, without authorisation, intentionally or fraudulently accessing a computer system, whether in whole or in part, to obtain data considered vital to national security.122

Cybersecurity legislation now criminalises unauthorised access to information deemed sensitive or confidential on the grounds that its disclosure could provoke public disorder and, under the amended Cybercrimes Act, the President may issue directives for the preservation, protection and overarching management of information infrastructure in the interest of national security,123 a provision that underpinned the government’s suspension of Twitter in 2021. A key informant confirmed instances of online censorship and overapplication of the Cybercrimes Act, linking these measures to the need to preserve Nigeria’s cyberspace in alignment with the NCPS, thereby suggesting that the NCPS has contributed to online restrictions, including the censorship of digital content.124

Amnesty International Nigeria’s director, Osai Ojigho, condemned the suspension of Twitter, emphasising that the platform serves as a vital medium for Nigerians to exercise fundamental rights, most notably freedom of expression and access to information, and arguing that the measure contravened Nigeria’s international human rights obligations, urging authorities to rescind the suspension, halt media suppression, preserve civic space and uphold citizens’ rights.125 This stance found legal resonance in the case of SERAP v Federal Republic of Nigeria before the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice, where a coalition of civil society organisations challenged the Twitter suspension, arguing that it violated article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter) and article 19 of ICCPR.126

Article 9 of the African Charter guarantees individuals the right to receive information and to express and disseminate their opinions ‘within the law’. It therefore protects the ability of persons and the press to exchange information and viewpoints across public fora. Similarly, article 19 of ICCPR secures the right to hold opinions without interference and the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, subject only to restrictions that are provided by law and demonstrably necessary and proportionate to a legitimate aim.127 The Nigerian action failed this test in practice because it was a broad, platform-wide restriction that was not narrowly targeted, lacked transparent procedural safeguards, and imposed a disproportionate constraint on the public’s ability to communicate and obtain information.

In its 2022 judgment, the Court held that Nigeria’s suspension of Twitter from June 2021 to January 2022 infringed the applicants’ rights to access information and media freedom under both instruments, stressing that these frameworks protect not only free speech but also the derivative right to access information, an adjunct essential for the full enjoyment of expression rights. Furthermore, Anyim and Okereke note that Twitter can serve as an important evidentiary source, with user-generated content increasingly recognised as admissible in Nigerian courts,128 while Obiora and others observe that, although irregular, the Nigerian government’s repeated suspension of access to social media platforms reveals a troubling inclination to control digital spaces to stifle dissent and restrict the flow of information.129

5.4 Implementation and infrastructure barriers undermining internet access

Lawal and others argue that framing internet access as a human right derives from broader principles of freedom of expression and the right to information.130 In Nigeria, however, the absence of explicit constitutional or statutory recognition of internet access has significant implications for civil liberties, particularly when the state resorts to network shutdowns or imposes restrictive regulations. While section 39(1) of the 1999 Constitution guarantees freedom of expression, it does not explicitly provide for its exercise through digital or online platforms. This legal gap contributes to limited public awareness of any entitlement to internet connectivity.

A key informant noted that persistent challenges to internet access in Nigeria include unclear regulatory guidelines on permissible online activity, underdeveloped network infrastructure and weak enforcement mechanisms requiring telecommunications operators to ensure reliable service.131 The classification of internet access as a fundamental human right remains a subject of international debate. Although many countries have yet to accord it explicit legal recognition, there is growing consensus that universal connectivity is essential to full participation in contemporary society.132 The UN has called on all member states to recognise ‘universal access to the internet’ as a basic human right by 2030, emphasising that the internet not only enables the exercise of pre-existing human rights, but is increasingly regarded as a right in its own capacity.133

Despite the rapid expansion of internet usage in Nigeria, digital freedoms are under mounting pressure as governments implement policies that allow for partial or total disruption of access. These restrictions often manifest as the suspension of telecommunication networks, including internet services, thereby impeding the free exchange of information. In more authoritarian contexts, such measures are compounded by extensive surveillance, censorship and deliberate shutdowns, all of which curtail citizens’ rights to freedom of information and expression.134

Rather than encountering explicit policy restrictions, users in Nigeria face substantial implementation gaps. Beyond technical limitations, persistent infrastructure deficits continue to widen the nation’s digital divide. In many rural communities, reliable broadband and mobile coverage remain scarce, compelling residents to travel considerable distances simply to send an email or access current news. These findings corroborate Oyedeji and others’ observation that high operational costs and a shortage of local expertise constitute significant impediments within Nigeria’s cybersecurity landscape.135 Although federal agencies allocate considerable proportions of their annual information technology budgets to cybersecurity, signalling its perceived strategic importance, these investments do not consistently translate into effective security outcomes.

Exacerbating these infrastructural challenges, rising data tariffs serve as a significant de facto barrier. One informant reported that the cost of a modest data bundle can exceed their monthly subsistence budget, effectively excluding many Nigerians from meaningful online participation. This aligns with Okocha and Edafewotu’s conclusion that internet access in Nigeria is constrained by both the high cost of computing devices and prohibitively expensive connectivity, thereby deepening the digital divide.136

Moreover, the threat or reality of security-driven network disruptions, exemplified by the Twitter ban from June 2021 to January 2022 and shutdowns during the #EndSARS protests, reflects the expansive interpretation of ‘national security’ embedded in the NCPS. Such actions demonstrate how broadly worded cybersecurity provisions can be deployed to restrict communication rather than to protect connectivity. One respondent observed that internet shutdowns, typically justified by the government as countermeasures against terrorism and violent extremism, inadvertently deprive citizens of their right to access information online.

For instance, during counter-terrorism operations in the north-eastern region, the Nigerian government suspended network services for over a month. While intended to disrupt insurgent activities, this measure significantly infringed upon citizens’ rights to communicate and to access the internet. This finding reinforces Lawal and others’ argument that, in Nigeria, the absence of explicit legal recognition of internet access has profound implications for civil liberties, particularly when authorities resort to network shutdowns or impose restrictive regulations.137

6 Conclusion

Nigeria’s formal cybersecurity framework, embodied in the NCPS, the Cybercrimes Act (with its 2024 amendment) and the NDPA, contains many of the building blocks of modern cybersecurity and data protection regimes, but the empirical evidence assembled in this article reveals a persistent policy-practice gap with material consequences for citizens’ digital rights. In short, securitising language in policy documents has legitimised expansive authorising mechanisms. Those mechanisms have been operationalised in ways that increase surveillance capacity, accelerate content removal and platform restrictions, and aggravate practical barriers to internet access. Oversight and remedial structures that exist on paper are routinely weakened by broad statutory carve-outs, implementation shortcuts and limited resourcing.

Three clear conclusions emerge. First, the way cyber threats are described shapes policy: Portraying risks as existential makes extraordinary powers easier to justify and then turns them into routine practice. Second, the choice of legal instruments is crucial: Provisions that mandate extensive data retention or permit rapid content takedowns often lead to predictable harms – such as privacy violations, suppression of speech and restricted access – unless carefully and narrowly circumscribed. Third, oversight is weak: Judicial and regulatory safeguards exist on paper but often lack the independence, resources or procedural clarity to prevent abuse.

To address the policy-practice gap identified in this article, we recommend a focused package of mechanism-level reforms that together can restore balance between security and rights. Specifically, require prior independent authorisation (judicial or equivalent independent body) for intrusive surveillance and any bulk data retention; replace blanket retention rules with narrowly targeted, time-limited orders; and strengthen the Nigeria Data Protection Commission (NDPC) by guaranteeing its operational independence, investigative powers and adequate resourcing. Complementary reforms should narrow and precisely define lawful grounds for content removal, mandate public transparency reporting by agencies and platforms, institutionalise multi-stakeholder policy making and accessible user redress, and invest in resilient, affordable connectivity and public digital rights literacy.

Finally, implement an empirical monitoring programme, public logging of takedown and retention requests, periodic stratified surveys on self-censorship and access, and operational case studies with response agencies, so that the effects of reforms can be measured and iteratively improved. Together, these measures target the mechanisms that have turned securitising frames into routine rights-curtailing practices and, if implemented in concert, can better protect citizens’ digital rights while preserving legitimate cybersecurity goals.

-

1 AI Denysov and others ‘Protection of critical infrastructure facilities as a component of the national security’ (2021) 39 Cuestiones Políticas 789.

-

2 As above; C Sfintes ‘Personal security – National security component or not? (2023) 1 Analele Universitǎti̧i Constantin Brâncuşi Din Târgu Jiu. Serie Litere Și Ştiinţe Sociale 177-182.

-

3 United Nations National security planning module 3.4 5, https://www.un.org/ssr/sites/www.un.org.ssr/files/general/module_3.4_national_security_planning_2.pdf (accessed 14 January 2025).

-

4 D Gordilă ‘Historical aspects of the evolution of national security in the Republic of Moldova’ (2024) 18 Agora International Journal of Juridical Sciences 185.

-

5 M Olausson ‘Review of Fortified settlements in early medieval Europe: Defended communities of the 8th-10th centuries’ (2017) 20 European Journal of Archaeology 541-543.

-

6 A Rahman ‘The concept of national security in the period of Cold War and post-Cold War’ (2023) 11 Journal of Law and Sustainable Development e766.

-

7 J Kaur & K Ramkumar ‘The recent trends in cyber security: A review’ (2022) 34 Journal of King Saud University – Computer and Information Sciences 5766; GU Osimen and others ‘The weaponisation of artificial intelligence in modern warfare: Implications for global peace and security’ (2024) 5 Research Journal in Advanced Humanities 24.

-

8 H Ahmed Hassan & K Sahar-Wahab ‘Review vehicular ad hoc networks security challenges and future technology: Networks security challenges and future technology’ (2022) 1 Wasit Journal of Computer and Mathematics Science 1; BO Daudu and others ‘Sustainable smart cities in African digital space’ in W Pawan and others (eds) Book artificial intelligence and machine learning for sustainable development (2025) ch 8.

-

9 GU Osimen and others ‘Artificial intelligence and arms control in modern warfare’ (2024) 10 Cogent Social Sciences 2407514.

-

10 S Kemp Digital 2024: Nigeria (2024) DataReportal, https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-nigeria (accessed 26 September 2025).

-

11 UV Awhefeada & OO Bernice ‘Appraising the laws governing the control of cybercrime in Nigeria’ (2020) 8 Journal of Law and Criminal Justice 30-49.

-

12 Ministry of Communication Technology Nigeria national ICT policy (Final draft 2012) (2012) ICT Policy Africa, https://ictpolicyafrica.org/en/document/3fb9w5vigsn?page=13 (accessed 26 September 2025); Awhefeada & Bernice (n 11).

-

13 N Eze-Michael ‘Internet fraud and its effect on Nigeria’s image in international relations’ (2021) 11 Covenant Journal of Business and Social Sciences 1.

-

14 OC Oyedeji and others ‘Assessing the efficiency of contemporary cybersecurity protocols in Nigeria’ (2024) 13 International Journal of Latest Technology in Engineering, Management and Applied Science 52.

-

15 FRN National cybersecurity policy and strategy (FGN/NCPS/2014) Federal Ministry of Communication Technology, http://www.nitda.gov.ng/cybersecurity (accessed 10 January 2025).

-

16 BO Daudu, GU Osimen & AT Abubakar ‘Artificial intelligence, FinTech, and financial inclusion in African digital space’ in V Sharma and others (eds) FinTech and financial inclusion: Leveraging digital finance for economic empowerment and sustainable growth (2025) 268.

-

17 FRN National cybersecurity policy and strategy (FGN/NCPS/2021) Federal Ministry of Communication Technology, http://www.nitda.gov.ng/cybersecurity (accessed 10 January 2025).

-

18 DM Molwantwa ‘Aligning the constitutional rights of citizens with cybersecurity measures in South Africa’ Doctoral thesis, North-West University, 2019; A Adegoke Digital rights and privacy Nigeria (Paradigm Initiative 2020); A Adegoke ‘The Universal Periodic Review and digital rights protection in Nigeria and South Africa’ (2022) (Order 30701927) ProQuest One Academic (2901488645), https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/universal-periodic-review-digital-rights/docview/2901488645/se-2 (accessed 26 September 2025).

-

19 Human Rights Watch ‘Nigeria: A year on, no justice for #EndSARS crackdown’

19 October 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/10/19/nigeria-year-no-justice-endsars-crackdown (accessed 3 October 2025). -

20 Adegoke Digital rights and privacy in Nigeria (n 18).

-

21 Paradigm Initiative & OONI ‘Status of internet freedom in Nigeria, 2018’ (2018), https://ooni.torproject.org/documents/nigeria-report.pd (accessed 17 January 2025).

-

22 O Daniels ‘National cybersecurity policy and strategy of Nigeria: A case study’ Doctoral thesis, ProQuest One Academic, 2023, https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/national-cybersecurity-policy-strategy-nigeria/docview/2825021029/se-2 (accessed 26 September 2025); JI Egerson and others ‘Cybersecurity strategies for protecting big data in business intelligence systems: Implications for operational efficiency and profitability’ (2024) 23 World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 916; Oyedeji and others (n 14).

-

23 V Braun & V Clarke ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’ (2006) 3 Qualitative Research in Psychology 77.

-

24 Braun & Clarke (n 23) 86-94.

-

25 HREC Protocol Assigned Number: CHREC/1174/2025; NHREC Registration Number: NHREC/CU-HREC/1/01/2025; IORG ID: IORG0010037) (on file with the authors).

-

26 Molwantwa (n 18) 10-11.

-

27 As above; A Loishyn and others ‘Development of the concept of cybersecurity of the organisation’ (2021) 10 TEM Journal 1447-1453.

-

28 Molwantwa (n 18) 10-11.

-

29 EE Akpan ‘A strategic assessment of cyber security strategies and mitigation of cybercrime in Nigeria’ (2019) 5 GASPRO International Journal of Eminent Scholars 1-10.

-

30 As above.

-

31 M Alabi Literature review on cybersecurity in Nigeria (2024).

-

32 C Haddad & C Binder ‘Governing through cybersecurity: National policy strategies, globalized (in-)security and sociotechnical visions of the digital society’ (2019) 44 Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 115.

-

33 L Kovács ‘National Cybersecurity Strategy Framework’ (2019) 18 AARMS – Academic and Applied Research in Military and Public Management Science 65; O Ochoga and others ‘Assessing the security implications of the ECOWAS protocol on free movement in Nigeria’ (2025) 8 International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies.

-

34 ITU Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) 2024: Measuring commitment to cybersecurity (2024) Geneva, Switzerland: ITU, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Cybersecurity/Documents/GCIv5/2401416_1b_Global-Cybersecurity-Index-E.pdf (accessed 24 January 2025).

-

35 AA Adonis ‘International law on cybersecurity in the age of digital sovereignty’ (2020) E-International Relations, https://www.e-ir.info/2020/03/14/international-law-on-cyber-security-in-the-age-of-digital-sovereignty/ (accessed 26 September 2025); P Barlow ‘A declaration of the independence of cyberspace’ (1996) Electronic Frontier Foundation, http://homes.eff.org/~barlow/Declaration-Final.html (accessed 27 January 2025); JA Lewis ‘Sovereignty and the role of government in cyberspace’ (2010) 16 Brown Journal of World Affairs 55.

-

36 A Kharlamov & G Pogrebna ‘Using human values-based approach to understand cross-cultural commitment toward regulation and governance of cybersecurity’ (2021) 15 Regulation and Governance 709; M Tvaronavičienė and others ‘Cyber security management of critical energy infrastructure in national cybersecurity strategies: Cases of USA, UK, France, Estonia and Lithuania’ (2020) 2 Insights into Regional Development 802.

-

37 WG Urgessa ‘Multilateral cybersecurity governance: Divergent conceptualisations and its origin’ (2020) 36 Computer Law & Security Review 105368; ND Nte, BK Enoke & JA Omolara ‘An evaluation of the challenges of mainstreaming cybersecurity laws and privacy protection in Nigeria’ (2022) 3 Journal of Law and Legal Reform 243.

-

38 Q Lanzendorfer ‘Government and industry relations in cybersecurity:

A partnership for the fifth domain of warfare’ (2021) 3 International Journal of Cyber Research and Education 48. -

39 Open-ended Working Group on the Security of and in the Use of Information and Communications Technologies Open-ended Working Group on Security of and in the Use of Information and Communications Technologies (2021-2025) (United Nations, 2021).

-

40 ND Nte, BK Enoke & VA Teru ‘A comparative analysis of cyber security laws and policies in Nigeria and South Africa’ (2022) 8 Law Research Review Quarterly 233.

-

41 Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs 2023–2030 Australian Cyber Security Strategy (2023), https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/cyber-security-subsite/files/2023-cyber-security-strategy.pdf (accessed 12 February 2025).

-

42 Prime Minister’s Office of Finland Finland’s Cyber Security Strategy 2024–2035 (2024) (Publications of the Prime Minister’s Office 2024:13), https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/165893/VNK_2024_13.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 14 February 2025).

-

43 D Bote ‘The South African national cyber security policy framework: A critical analysis’ Doctoral thesis, North-West University, 2019.

-

44 As above.

-

45 ITU (n 34) 24-25.

-

46 G Greenleaf & B Cottier ‘International and regional commitments in African data privacy laws: A comparative analysis’ (2022) 44 The Computer Law and Security Report 105638.

-

47 U Orji ‘An inquiry into the legal status of the ECOWAS Cybercrime Directive and the implications of its obligations for member states’ (2019) 35 Computer Law and Security Review 105330.

-

48 ECOWAS Supplementary Protocol A/SP.1/06/06 on Democracy and Good Governance (2006) ECOWAS, aa-ecowas-official-journal-dated-2006-06-01-vol-49.pdf (accessed 16 February 2025); ECOWAS Revised treaty of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) (2010), https://ecowas.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Revised-treaty-1.pdf (accessed 18 February 2025).

-

49 A Mravcová ‘Toward environmental citizenship: The concept of citizenship and its conceptualisation in the context of global environmental challenges’ (2023) 59 Studia Philosophiae Christianae 69.

-

50 Aristotle The Politics (1990).

-

51 Mravcová (n 49) 69-90.

-

52 B Rutte ‘Realising the right to citizenship’ in B von Rütte (ed) The human right to citizenship: Situating the right to citizenship within international and regional human rights law (2022).

-

53 J Bartels & W Schramade ‘Investing in human rights: Overcoming the human rights data problem (2024) 14 Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment 199.

-

54 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed 31 January 2025).

-

55 F Duarte ‘TH Marshall is alive! A manifesto for a 21st-century public welfare state’ (2018) 6 Critical and Radical Social Work 51-65.

-

56 As above.

-

57 L Caldwell ‘Cybersecurity as a human right: A reformulation of the theoretical framework of securitisation theory’ Doctoral thesis, Northcentral University, 2022.

-

58 C Howell & D West ‘The internet as a human right’ Brookings Institution (2016).

-

59 R Shandler ‘The pandemic shows we depend on the internet. So is internet access a human right’ The Washington Post 2020.

-

60 D Dror-Shpoliansky & Y Shany ‘It’s the end of the (offline) world as we know it: From human rights to digital human rights – A proposed typology’ (2021) 32 European Journal of International Law 1249.

-

61 As above; L Pangrazio & J Sefton-Green ‘Digital rights, digital citizenship and digital literacy: What’s the difference?’ (2021) 10 Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 15.

-

62 Pangrazio & Sefton-Green (n 61).

-

63 As above.

-

64 M Kothari ‘The sameness of rights online and offline’ in M Susi (ed) Human rights, digital society and the law: A research companion (2019) 15-30.

-

65 As above.

-

66 I Bieliakov and others ‘Digital rights in the human rights system’ (2023) 10 InterEULawEast: Journal for the International and European Law, Economics and Market Integrations 183-207.

-

67 O Akeredolu ‘Digital right advocacy: Advocacy for life in the digital world’ (2021) 4 International Journal of Social Science and Human Research 2471.

-

68 M Estrada ‘Revisiting access to internet as a fundamental right in times of COVID-19’ (2020) 6 UNIO – EU Law Journal 15.

-

69 As above.

-

70 P Gibbons The freedom of information officer’s handbook (2019).

-

71 A Singh ‘Digital right management and access to knowledge’ (2024) 16 CPJ Law Journal 205-214.

-

72 Translated by Content Engine LLC Right to information vs right to privacy: Freedom of expression and protection of personal data (2022).

-

73 M Mute Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (2019), https://achpr.au.int/en/special-mechanisms-reports/declaration-principles-freedom-expression-2019 (accessed 9 February 2025).

-

74 Nigeria’s Freedom of Information Act (2011).

-

75 Singh (n 71) 205-207.

-

76 Freedom of Expression and ICTs (2013) Overview of international standards, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/legalcode (accessed 4 Feb-ruary 2025).

-

77 C Kettemann & W Benedek ‘Freedom of expression online’ in M Susi (ed) Human rights, digital society and the law: A research companion (2019) 1-399).

-

78 As above.

-

79 M Pfisterer ‘The right to privacy – A fundamental right in search of its identity: Uncovering the CJEU’s flawed concept of the right to privacy’ (2019) German Law Journal 722-733.

-

80 A Alibeigi and others Right to privacy, a complicated concept to review (2019).

-

81 As above.

-

82 P Schwarz ‘Street photography and the right to privacy: The tension between freedom of artistic expression and an individual’s right to privacy in the USA’ (2020) Cognitio (Luzern) 1-15.

-

83 DJ Solove ‘The limitations of privacy rights’ (2023) 98 The Notre Dame Law Review 975-1036.

-

84 Oyedeji and others (n 14) 53-54.

-

85 O Osho & D Onoja ‘National cyber security policy and strategy of Nigeria:

A qualitative analysis’ (2015) 9 International Journal of Cyber Criminology 120; Nte and others (n 40). -

86 FRN (n 15) para 4.

-

87 As above; FRN (n 17) 10-13.

-

88 As above.

-

89 As above.

-

90 B Ikusika ‘A critical analysis of cybersecurity in Nigeria and the incidents of cyber-attacks on businesses/companies’ (2022) Companies (15 July 2022).

-

91 As above.

-

92 C Agwuegbo ‘Reclaiming Nigeria’s shrinking online civic space’ (2021), byy0nB4ltwzup7CGEyg8iqdvwYUNwTtjxKHeT66S.pdf (accessed 20 February 2025).

-

93 B Buzan and others Security: A new framework for analysis (1998).

-

94 C Eroukhmanoff ‘Securitisation theory’ (2017) E-international Relations.

-

95 Buzan and others (n 93) 23-27.

-

96 R Taureck ‘Securitisation theory and securitisation studies’ (2006) 9 Journal of International Relations and Development 53-61.

-

97 FRN (n 17) i-iii.

-

98 Adegoke ‘The Universal Periodic Review’ (n 18).

-

99 A Salisu and others ‘Cybersecurity policy effectiveness in shaping safe online behaviour: A focus on Nigerian tertiary students in the northeast’ (2024) 6 Journal of Scientific Development Research 137-150.

-

100 Paradigm Initiative News statement on the state of freedom of expression in Nigeria and the NITDA code of practice (Targeted News Service 2002).

-

101 F Anyogu & I Nwachukwu ‘Hate speech and constitutional safeguards to freedom of expression in Nigeria: A review (2021) 2 LASJURE 125.

-