Japheth Biegon

LLB (Moi) LLM LLD (Pretoria)

Africa Regional Advocacy Coordinator, Amnesty International; Extraordinary Lecturer, Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4905-6470

The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal and do not in any way reflect or represent the positions of Amnesty International.

Edition: AHRLJ Volume 24 No 2 2024

Pages: 854 - 889

Citation: J Biegon ‘The impact of country-specific resolutions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1994-2024’ (2024) 24 African Human Rights Law Journal 854-889

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2024/v24n2a18

Download article in PDF

Summary

This article analyses the impact of the country-specific resolutions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights using a theoretical framework constructed around the concept of ‘naming and shaming’. The Commission’s country-specific resolutions focus on the human rights situation in named countries. While the Commission has consistency adopted these resolutions since 1994, very little is known about their impact. The article attempts to fill this gap in the literature by presenting evidence of the extent to which country-specific resolutions issued by the Commission have been complied with. It analyses nine resolutions, selected because they contain specific recommendations that would allow for the possibility of analysing impact with some level of accuracy. An analysis of these resolutions, adopted in seven countries (Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Kenya, Nigeria and Zimbabwe) reveals that immediate full compliance is rare. At best, the Commission’s country-specific resolutions have triggered discursive engagements that have resulted in tentative changes in human rights practices or situational compliance as a result of changes in government or political circumstances.

Key words: African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights; country-specific resolutions; impact; naming and shaming; implementation; compliance

1 Introduction

A typical function of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Commission) is to monitor the situation of human rights on the continent. When it detects a reason for serious concern or a dire situation is brought to its attention, the Commission often responds through a variety of means. First, it may send an urgent appeal or a letter of concern to the concerned government. Urgent appeals mostly deal with time-sensitive cases including those that present the danger of irreparable harm.1 Second, the African Commission may publish a press statement on its website.2 Third, the Commission may adopt a country-specific resolution outlining its concern(s) and recommending specific action(s) to be undertaken by the targeted country.

The above three options serve more or less the same purpose. The choice of one option over the other appears to be an issue of timing. On the one hand, urgent appeals, letters of concern and press statements are mainly issued during the Commission’s inter-session periods.3 They are initiated and signed off by individual commissioners in their capacity as country rapporteurs or special mechanism mandate holders. A vote or consensus among the commissioners is not a prerequisite for their issuance, although the Commission’s bureau ordinarily gives its approval prior to publication. On the other hand, country-specific resolutions are exclusively considered during and issued at the end of the formal sessions of the Commission. They reflect the position taken by the majority of the commissioners either by way of a vote or consensus.

This article is concerned with the impact of the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions. The aim of such resolutions is to put public pressure on the target countries to align their conduct with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter) and/or its applicable protocols. The resolutions shine a spotlight on and call international attention to human rights violations and abuses. The mobilisation of this kind of public pressure, commonly known as ‘naming and shaming’, is an entrenched methodology for advancing human rights. Popularised by international human rights organisations,4 naming and shaming is so rooted a strategy that it has become ‘the principal weapon of choice among many international organisations and governments’.5 The strategy has gained significant traction given the rapid diffusion of news and information in the present world.

To the extent that they are intended to mobilise public pressure through naming and shaming, the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions operate in ways similar to those of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council (HRC).6 The resolutions are also comparable to those that were routinely adopted by the UN Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) before it was disbanded and replaced by the HRC.7 Likewise, the Commission’s country-specific resolutions serve a purpose similar to that of country reports of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (Inter-American Commission).8 These reports gained prominence during the 1970s and 1980s, a period during which many countries in Latin America were under authoritarian rule. Through publication of country reports, the Inter-American Commission established itself as a fierce critic of human rights violators in the region.9

Scholars have examined the impact of the resolutions of both the HRC and its predecessor. Through extensive research, we now know that despite the fact that the targeting of states by the UNCHR through resolutions was encumbered by political bias,10 an increasing number of repressive states were forced to engage with the body if only to defend themselves.11 We also know that countries that were often the subject of UNCHR resolutions experienced reductions in foreign aid from multilateral financial institutions such as the World Bank.12 Beyond the resolutions of the UNCHR/HRC, a considerable amount of ink has also been spilt examining the naming and shaming effect of the rulings of the UN Human Rights Committee,13 as well as the nature of state responses to country-specific activities of UN special procedures.14 Scholars have also scrutinised the impact of the Inter-American Commission’s country reports,15 with some reaching the conclusion that the pressure accompanying the reports has contributed to a reduction of human rights violations in specific countries.16

On the contrary, very little is known about the impact of the country-specific resolutions of the African Commission.17 Do states care if they are criticised or condemned by the Commission? Do they respond to the Commission’s country-specific resolutions? If they do not respond, what explains their silence or indifference? If they respond, what is the nature of the response? Have the resolutions impelled any form of change in state conduct? If naming and shaming serves as a megaphone for building pressure,18 are the Commission’s country-specific resolutions loud enough or loud at all? Building upon previous research on naming and shaming, the analysis in this article is an attempt to respond to these questions with a view to filling the gap in the literature.

In terms of structure, this article is divided into five parts. This part introduces the subject of discussion. Part 2 provides a description of the nature and role of the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions. This includes a statistical analysis showing trends and patterns in the Commission’s practice of adopting country-specific resolutions. Part 3 presents the conceptual framework that underpins the analysis of the impact of the country-specific resolutions. It categorises impact into two broad categories: direct impact (changes in states’ human rights practices) and indirect impact (states’ discursive responses to the Commission’s resolutions). This part also discusses the methodology used to gather data for the study. Part 4 presents evidence of the impact of the Commission’s country-specific resolutions. In addition to broad overviews of cases of compliance and non-compliance in Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Kenya and Zimbabwe, the part provides in-depth impact analyses in The Gambia and Nigeria. Part 5 draws the article to a conclusion.

2 Nature and role of country-specific resolutions

Country-specific resolutions focus on the human rights situation in specific countries. Described as an expression of ‘audacity on the part of [Commission] members’,19 country-specific resolutions shine a spotlight on and seek to mobilise public pressure against repressive practices and gross human rights violations and abuses. In this context, the Commission utilises country-specific resolutions as a naming and shaming tool, although on at least one occasion it has adopted a resolution applauding positive developments in the targeted country.20

Country-specific resolutions follow a common pattern in their structure. After citing relevant provisions of the African Charter or any other relevant instrument, and after recalling pertinent previous developments, the African Commission expresses its ‘concern’ or ‘deep concern’, or it indicates that it is ‘disturbed’ or ‘alarmed’ by the human rights situation in the target country. It then ‘condemns’, ‘deplores’ or ‘regrets’ this situation and ‘calls upon’ the target country to address or remedy the situation. The condemnatory language used by the Commission in country-specific resolutions has been described by one commentator as ‘very robust’.21

The African Commission has also used country-specific resolutions to alert countries to the potential of certain developments to increase the likelihood of human rights violations.22 In this way, country-specific resolutions play the role of an early warning or preventive tool. Country-specific resolutions may also serve as a follow-up tool, that is, when they are used to push a state to implement a previous decision of the African Commission taken, for instance, under its complaint or communications procedure.23 They may also be used to highlight the plight of a particular group of people in a country such as human rights defenders,24 journalists and media practitioners,25 and women.26

Although country-specific resolutions are adopted as part of the African Commission’s promotional mandate, they may also serve a quasi-protective role.27 They provide the Commission with the opportunity to consider and comment on the human rights situation in countries against which no complaint has been lodged. The Commission has not had the opportunity to adjudicate a complaint involving several countries targeted by country-specific resolutions, including Comoros, Guinea Bissau and Somalia. Country-specific resolutions are also relevant in respect of countries that have never complied with their reporting obligation (Comoros, Guinea Bissau, Somalia and South Sudan) or which complied at some point but subsequently lapsed into non-compliance (for example, Burundi, Central African Republic (CAR), Guinea and Sudan).28

Despite its consistency in adopting country-specific resolutions, the Commission has not developed any guidelines outlining the circumstances that warrant their issuance. In April 2016 the Commission established the Resolutions Committee, an internal subsidiary mechanism mandated with the task of ‘collect[ing] data and information on situations of human rights violations on the continent that may be addressed in resolutions and make proposals to the Commission’.29

As of mid-November 2024, the African Commission had adopted a total of 141 country-specific resolutions targeting 39 state parties to the African Charter. The Commission also adopted four omnibus resolutions focusing on the human rights situation on the entire continent during the same period. The Commission should ordinarily be concerned with the human rights situation in state parties to the African Charter. However, it has adopted two resolutions on the situation in Palestine, a non-state party to the African Charter.30

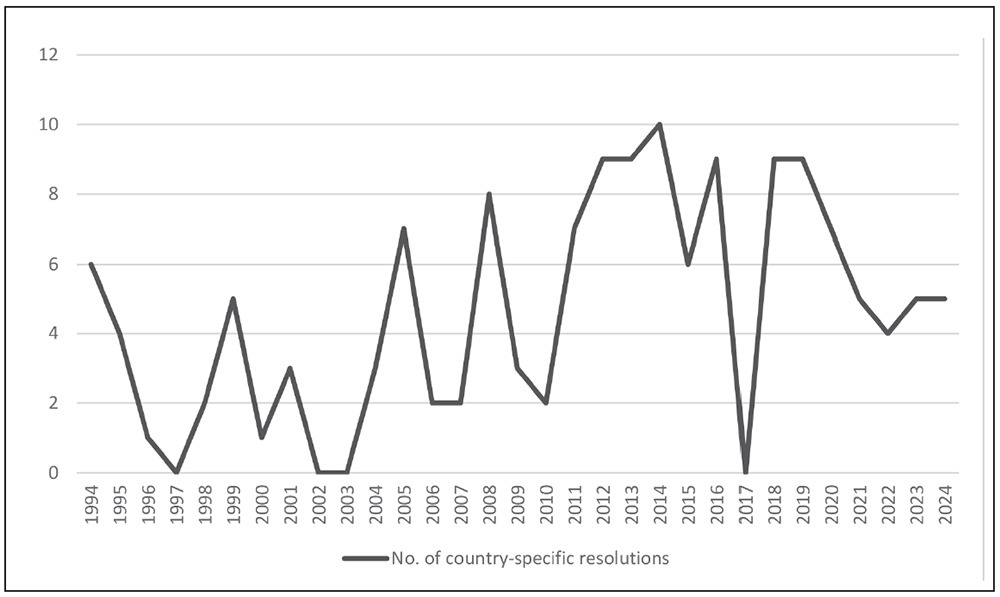

Graph 1 below shows the number of country-specific resolutions adopted each year from 1994 to 2024. It reveals that the number of resolutions adopted on an annual basis by the African Commission has progressively increased over the last 30 years. From 1994 to 2003, the Commission adopted a total of 22 country-specific resolutions, which translated to an average of 2,2 resolutions per year. The rate of adoption more than doubled in the second decade (2004-2013) to a total of 50 resolutions and an annual average of five resolutions. From 2014 to 2024, the annual average increased to 6,8 resolutions.

Graph 1: Annual adoption of country-specific resolutions, 1994-2024

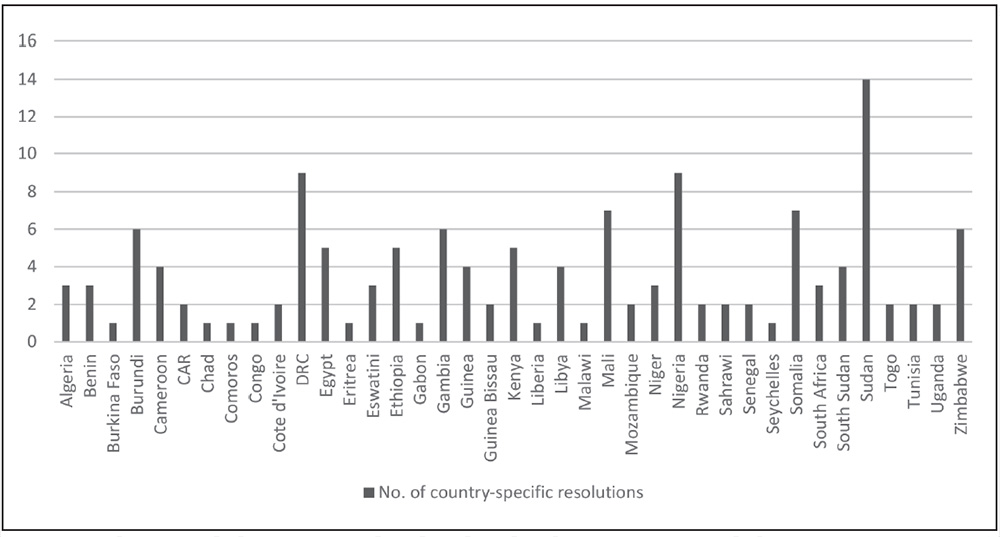

Graph 2: Target countries of country-specific resolutions, 1994-2024

Graph 2 above shows the number of resolutions adopted in respect of each of the 39 state parties. With 14 resolutions, Sudan has attracted the most country-specific resolutions (10 per cent). The timing of these resolutions largely corresponds to the periods in the country’s history when it has been engulfed in conflict. In descending order, Sudan is followed by the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (nine); Nigeria (nine); Mali (seven) and Somalia (seven), all of which have also grappled with protracted conflicts. Other countries that have attracted a relatively large number of resolutions are Burundi, Egypt, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Kenya and Zimbabwe. With 33 resolutions in total, these countries cumulatively account for 24 per cent of all country-specific resolutions. They have experienced episodes of human rights crisis and repression at particular points in their history.

The human rights violations and abuses that motivate the African Commission to adopt country-specific resolutions are myriad. A textual analysis of the resolutions revealed six broad categories: conflict and violence; elections or unconstitutional changes of governments or coups d’état; socio-economic rights; non-compliance with Commission decisions or state reporting obligations; repression; and the rights of marginalised groups, especially women. Table 1 below shows the results of the classification of the resolutions into the six broad categories.31

Table 1: Subject-matter of country-specific resolutions, 1994-2024

|

Subject |

Number of resolutions |

% |

|

Conflict/violence |

61 |

45 |

|

Election/coup |

17 |

13 |

|

ESCR |

6 |

4 |

|

Non-compliance |

2 |

2 |

|

Repression |

43 |

32 |

|

Marginalised groups |

6 |

4 |

Nearly half (45 per cent) of all the country-specific resolutions address human rights violations committed in the context of conflict or widespread violence. Long before the African Commission created the Focal Point on Human Rights in Conflict Situations in February 2016,32 country-specific resolutions were already playing the crucial role of highlighting human rights violations committed in conflict.33 The resolutions still play this crucial role and often reflect the convergence of international human rights law and international humanitarian law in the work of the Commission.34

Repressive practices account for the second most important motivation for the Commission’s country-specific resolutions. Out of the 141 country-specific resolutions adopted by the Commission in the last three decades, 43 (or 32 per cent) relate to situations in which the Commission is concerned about systemic or an upsurge of violations of civic freedoms in a context of repression of dissent and critical voices. In this regard, repressive practices covered in country-specific resolutions include the following: arrest and detention of government critics and human rights activists; torture, killings and enforced disappearances; and clampdown on freedoms of expression, association and assembly.

Closely related to the scourge of conflict in Africa is the phenomenon of electoral violence and coups d’état or unconstitutional changes of governments. The African Commission has adopted 17 resolutions on this subject. Its position on invalidity of coups d’état, as expressed in these resolutions, predates both the African Union (AU) Declaration on Unconstitutional Changes of Government and the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (African Democracy Charter). Table 1 above reveals that socio-economic rights and the rights of marginalised groups have not featured prominently in country-specific resolutions. This may suggest a preference to address concerns relating to the two subjects through thematic resolutions.

3 Conceptualising and measuring impact

This article analyses the impact of the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions using a theoretical framework constructed around the concept of naming and shaming. This is the ‘act of framing and publicising human rights information in order to pressure states to comply with human rights standards’.35 In this context, naming and shaming falls under the broader category of ‘human rights pressures’, which Hawkins defines as ‘non-violent activities carried out by transnational networks and states with the primary purpose of improving individual rights by creating economic and political costs for a repressive government’.36

Naming and shaming countries, as the African Commission does in country-specific resolutions, may trigger two possible forms of impact. It may have a direct impact by contributing to changes in the state’s conduct. Executions may be stayed, detainees released, investigations opened, or forced evictions suspended. Alternatively, or additionally, naming and shaming may have an indirect impact by jolting the concerned state into a discursive engagement with the African Commission. Naming and shaming may also influence policy decisions of third parties regarding the target country, or it may empower and support the human rights activism of domestic constituencies.

3.1 Direct impact

The underlying logic of direct impact is that ‘action’ is impact. Naming and shaming achieve what Franklin describes as the ‘highest level of influence’ when the target state changes its conduct or behaviour to conform to human rights norms and principles.37 In this context, direct impact may be defined as ‘an immediate and acknowledged shift in state repressive practices’.38 Direct impact essentially connotes compliance with the Commission’s country-specific resolutions. The term ‘compliance’ refers to ‘a state of conformity or identity between an actor’s behaviour and a specified rule’.39 In this study, compliance thus means the alignment of the factual situation in a target country with the Commission’s recommendations in a country-specific resolution.

Human rights change is naturally a process rather than an event. As such, compliance often occurs slowly as small and gradual steps build up to a point where the state’s behaviour conforms to or attains the expected standard. This brings into focus the related concept of implementation which is the process of putting in place measures to give effect to international commitments or decisions or recommendations of human rights treaty bodies.40 As is done in this article, the terms ‘compliance’ and ‘implementation’ are often used interchangeably, although the former is an outcome while the latter is the process that produces that outcome. As an outcome, a state’s level of compliance is best understood as a status that could potentially shift from non-compliance to either partial or full compliance.

It is also worth noting that compliance may be achieved independently of implementation. This may happen due to sheer coincidence or a change in circumstances that brings a state’s conduct into conformity with the expected behaviour, but without the state having taken the necessary deliberate steps to comply. This form of compliance is referred to as ‘situational’ or sui generis compliance.41

3.2 Indirect impact

The underlying logic of indirect impact is that ‘reaction’ or ‘response’ is impact.42 The African Commission adopts country-specific resolutions with the hope that they will elicit some form of response from a variety of actors, including the target country, a third party such as a donor or a multilateral institution, or from the local population in the target country. Such response may in the long run trigger the expected human rights change by prompting discourse, making information available to relevant actors, and creating or invigorating impetus for more pressure to be piled on the target country.

Although state responses to naming and shaming are context-specific, it is possible to identify a common pattern. Cohen classifies state responses to human rights criticism into three mutually-inclusive categories, namely, denial, counteroffensive and acknowledgment.43 Most probably, a target country will first deny the allegation levelled against it. The country will argue that what it is criticised for never happened (literal denial) or that whatever happened is different from what it is accused of (interpretive denial). Alternatively, it will argue that what happened was justified for one reason or the other (implicatory denial).

Denial is usually accompanied by the second form of response: counter-offensive. When it responds in this manner, a target country will attempt to counter the criticism by making arguments that challenge the content of the criticism as well as the authority, credibility or the motive of the source. Lastly, a target country may acknowledge the wrongs for which it is criticised. Acknowledgment often is a ‘disarming type of response’ and may range from partial to full acknowledgment.44 That a target country acknowledges that it is in the wrong does not necessarily mean that it will remedy the wrong. In many cases, target countries initiate cosmetic changes to pacify criticism.

By responding to criticism, target countries inadvertently initiate a discourse that may push them into a corner where they are gradually socialised into proper human rights behaviour. In the literature, this process is referred to as ‘rhetorical entrapment’.45 The entrapment often begins when the target state denies the allegations levelled against it. The mere act of denial sets in motion a socialisation process.46 It sends a message to relevant actors that the target country cares about its human rights record even if it does so for instrumental reasons. With this knowledge, more pressure may be applied to the target country leading it to a stage where it acknowledges the wrong and makes tactical concessions. These concessions become the basis for even more demands. In effect, rhetorical entrapment converts words that were initially empty gestures into concrete action in favour of human rights.

Numerous case studies demonstrate that rhetorical entrapment has resulted in human rights changes in many parts of the world,47 including in Africa where there are compelling analyses of how the mechanism has operated in Kenya,48 Morocco,49 South Africa,50 Tunisia51 and Uganda.52 New research, however, reveals that states can engage in ‘reverse-rhetorical entrapment’.53 This means that state responses to human rights criticism may also entrap the source of the criticism and shape its strategy.

3.3 Methodological approach and caveat

This article uses the process-tracing methodology to establish causal links between the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions and state behaviour. It relies on information collected through an extensive desk research, involving a review of documents produced by the states, the African Commission, other regional or international bodies and civil society organisations. The bulk of the research was conducted as part of the author’s doctoral research at the Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria.54

It is important to note that searching for evidence of the impact of the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions is fraught with methodological challenges. One intractable problem relates to the fact that when they violate human rights, countries usually are subjected to criticism by multiple actors, including international or regional human rights bodies. Moreover, human rights criticism is frequently accompanied by other forms of human rights pressures, such as the threat of economic sanctions or the withdrawal of donor funding. Thus, it is difficult to tell which pressure is specifically responsible for particular state action. As Kamminga observes, few governments will openly admit that they have taken an action in response to international pressure.55

It follows that it is difficult to establish causal links between the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions and state behaviour. This problem is further exacerbated by the dearth of information on state responses to the Commission’s country resolutions. The Commission has not established a robust mechanism for gathering information about the impact of its work.

Another challenge relates to the low levels of precision and clarity in a good number of the Commission’s country-specific resolutions. As Viljoen observes, ‘[s]ome country-specific resolutions are so imprecise that they are almost meaningless’.56 Researchers seeking to determine the impact of country-specific resolutions of other international human rights bodies have experienced a similar problem.57 The analysis in this article focuses on resolutions that have a clear and specific demand on the target country.

4 Impact of the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions

On the occasion of its twentieth anniversary, a member of the African Commission claimed that the Commission’s country-specific resolutions had influenced state policies as well as public opinion on human rights practices in African countries.58 The task in this part is to find and analyse evidence of this influence or impact. The part begins with an explanation of the process undertaken to identify resolutions with clear and specific demands on the target country. It then provides a broad overview of the impact of the identified resolutions on the human rights practices of the target countries. This is followed by detailed case studies of the impact of the Commission’s country-specific resolutions in The Gambia and Nigeria.

4.1 Selection of resolutions

For purposes of analysing the impact of the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions, several resolutions were discounted or excluded from the scope of the study. A two-stage process was used to determine which resolutions to exclude. In the first stage, 17 resolutions were discounted because of the following six reasons:

(a) The resolution has the entire continent as its focus: Four omnibus resolutions on the situation of human rights in the entire continent were left out because they are concerned about the human rights situation on the entire continent.59

(b) The resolution is concerned about human rights issues beyond the continent: Two resolutions were discounted because they address the situation in Palestine, a non-African country.

(c) The resolution is not condemnatory: Five resolutions were eliminated because they are not framed in a naming and shaming language. Either they praise, show support for, or welcome a particular development. In other words, they are not condemnatory, and it thus is futile to apply the naming and shaming framework to determine the impact of these resolutions. For instance, Resolution 28 on Nigeria (1998) praised the country for reinstating democratic governance after several years of military rule.60 Similarly, Resolution 49 on Burundi (2000) expressed support for a peace agreement signed to end conflict in the country.61

(d) The resolution has no specific recommendation: Resolution 32 of 1998 on the Peace Process in Guinea Bissau was omitted because it makes no specific recommendation.62

(e) The resolution does not address a human rights situation: Resolution 39 on Seychelles was omitted because it is concerned with the country’s refusal to present its periodic state party report.63

(f) The main recommendations are not addressed to the target country: Four resolutions were omitted because they address their main recommendations to the Organisation of African Unity (OAU)/AU and other international bodies. These are Resolution 56 on Tunisia, Resolution 340 on Sahrawi Republic,64 Resolution 478 on Niger65 and Resolution 610 on Zimbabwe.66

In the second stage, the remaining 124 resolutions were examined to determine whether they contained specific recommendations that would allow for the possibility of analysing impact with some level of accuracy. Only nine resolutions were found to contain specific recommendations that suit the aims of this study. The recommendations in the other resolutions were deemed to be overly broad or imprecise. For example, they require the target country to restore peace or end continuing conflict or violence,67 respect or protect human rights in general,68 or they send mixed signals to the target country.69

The nine resolutions with specific recommendations relate to seven countries: Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Kenya, Nigeria and Zimbabwe. The resolutions fall into three broad overlapping categories, as shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Country-specific resolutions with specific recommendations

|

Recommendation |

Resolution |

|

|

1 |

Release specific detainees/conduct targeted investigations |

|

|

2 |

Implement specific decision |

|

|

3 |

Repeal or reform specific law |

|

Resolutions in the first category call for the release of specific detainees or for investigations into the death of detainees in custody. Resolution 16 on Nigeria called for the release of political prisoners, including 25 Ogoni community activists, detained in May 1994 after a riot. Resolution 134 on The Gambia called for the immediate and unconditional release of Chief Ebrima Manneh and Kanyie Kanyiba detained in the aftermath of an attempted coup d’état in March 2006.70 Resolution 360 on The Gambia called for investigations into the May 2016 death in custody of political activist Ebrima Solo Sandeng. Resolution 91 on Eritrea recommended the release of 11 former government officials detained in the country from 2001 without trial.71 Resolution 554 on Eswatini called for the release two members of parliament (MPs), Mduduzi Bacede Mabuza and Mthandeni Dube, who were arrested during pro-democracy protests in June 2021.72 The Resolution also recommended that the Eswatini government should establish an independent panel of inquiry to investigate the January 2023 killing of human rights lawyer, Thulani Maseko.

Resolutions in the second category call for implementation of specific decisions adopted in the complaints procedure of the African Commission. There are three resolutions in this category. Resolution 91 on Eritrea called on the government to comply with the Commission’s decision in the case of Zegveld & Another v Eritrea.73 This decision declared the detention without trial of 11 former government officials to be a violation of the African Charter and recommended their immediate release. Resolution 216 on Swaziland called for the implementation of the Commission’s decision in the case of Lawyers for Human Rights v Swaziland.74 In this case the Commission found that the 1973 Proclamation repealing the country’s 1968 Constitution and Bill of Rights violated a range of provisions in the African Charter insofar as it vested all executive, judicial and legislative powers in the King. The Commission recommended that the Proclamation be ‘brought in conformity with the provisions of the African Charter’ and that ‘the state engages with other stakeholders, including members of civil society in the conception and drafting of the new Constitution’.

Resolution 257 on Kenya called on the government to implement the African Commisn’s sio2009 decision in the case of Centre for Minority Rights Development (Kenya) and Minority Rights Group International on behalf of Endorois Welfare Council v Kenya (Endorois).75 In this decision the Commission found that the forceful removal of the Endorois indigenous community from their traditional land violated the African Charter. The Commission made six substantive recommendations, including that the traditional land be returned to the Endorois; the community be allowed unrestricted access to the land; royalties and adequate compensation be paid to the community; and that the community’s welfare organisation be registered.

Resolutions in the third category call for the repeal or reform of specific domestic laws. Resolution 218 on Ethiopia called on the government to ‘[a]mend the Charities and Civil Societies Proclamation in accordance with the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders’.76 Following its enactment in February 2009, the Proclamation was widely criticised for its excessive restrictions on human rights organisations.77 Resolution 89 on Zimbabwe called on the government to repeal or amend the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA), Broadcasting Services Act, and the Public Order and Security Act (POSA).78 In its 2002 report of the fact-finding mission to Zimbabwe, the Commission found that the use of these laws to require the registration of journalists or to prosecute them for publishing false information had a combined chilling effect on freedom of expression and had introduced ‘a cloud of fear in media circles’.79

4.2 Broad impact overviews

This part broadly examines the impact of the resolutions listed in Table 2 above in five countries: Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Kenya and Zimbabwe. As discussed below, the available evidence suggests that the concerned resolutions have been fully or partially complied with in Ethiopia, Kenya and Zimbabwe, but no similar impact has been recorded in Eritrea, Eswatini and Zimbabwe.

4.2.1 Cases of compliance

Ethiopia has implemented the recommendation in Resolution 218 to amend the 2009 Charities and Civil Societies Proclamation. Immediately after the adoption of Resolution 218, Ethiopia reacted negatively. At the Commission’s fifty-second ordinary session held in October 2012, the Ethiopian delegation expressed disapproval for the resolution and insinuated that it was prompted by ill motive and based on a draft resolution submitted to the Commission by the NGO Forum.80

However, following a change of government in 2018 that briefly ushered in a new era for human rights in the country, Ethiopia commenced the process of revising the 2009 Proclamation. This culminated in the enactment of a new CSO law in March 2019, the Organisation of Civil Societies Proclamation. The new law has created a generally-conducive legal and administrative environment for civil society operations, although some concerns remain.81 In its latest state party report to the Commission, dated January 2024, Ethiopia described the enactment of the new law as a ‘bold measure’ aimed at addressing the shortcomings of the 2009 Proclamation.82

On the face it, the repeal of the 2009 Proclamation presents evidence of the direct impact of Resolution 218 in Ethiopia. However, it is more accurate to conclude that the action of the Ethiopian government amounts to situational compliance. It was prompted by the change of government and internal circumstances in the country rather than a deliberate decision to implement the Commission’s resolution.

Resolution 257 on the implementation of the Endorois decision by Kenya has been partially complied with and it has thus registered some limited impact. A 2015 study found that out of the six substantive recommendations that the Commission made in the Endorois decision, only the one requiring registration of the Endorois Welfare Council had been fully implemented.83 The implementation of the other five recommendations was either ‘unclear’ or ‘pending’.84

A subsequent study found that a mechanism for the involvement of the Endorois in the management of the Lake Bogoria National Reserve had been established and that the community had been granted access to the reserve, albeit on an ad hoc basis.85 In September 2014, about 10 months after the Commission adopted Resolution 257, the Kenyan government established a task force for the implementation of the Endorois decision.86 This was initially viewed as a step in the right direction, but an analysis of the mandate and operations of the task force has led to the conclusion that it was but a smokescreen.87 More importantly, the task force has not published a report of its recommendations ten years after it was established.

Despite its initial negative reaction, Zimbabwe has also taken steps to comply with Resolution 89 of 2005 requiring it to amend or repeal three specific draconian pieces of legislation. In a January 2006 reply to the resolution, Zimbabwe demanded that the Commission revokes the resolution in its entirety because it was an ‘improper reproduction’ of a draft resolution submitted to it by non-governmental organisations (NGOs), particularly Amnesty International.88 Later in its periodic report submitted to the Commission in October 2006, Zimbabwe gave its strongest indication yet that it would not revise the impugned laws. It argued that the laws were progressive and ‘drew extensively from, and are similar, to laws from other countries particularly, the security and “gag” laws in other democracies like Britain, the USA, Australia and Canada’.89 In particular relation to the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act, Zimbabwe argued that it was enacted to bring accountability because private media operators had previously misinformed the public and used the media to advocate for regime change.90

In 2017 Zimbabwe underwent a political transition when Robert Mugabe resigned as President. Through a military-assisted transition, Emmerson Mnangagwa took over. In 2018 he was formally elected President in a general election. Building on the country’s 2013 Constitution, the Mnangagwa administration promised a new vision for Zimbabwe. Some of the reforms it has undertaken so far include the repeal of two of the impugned laws. In August 2019 Zimbabwe enacted the Maintenance of Peace and Order Act (MOPA) to replace the POSA. Another new law, the Freedom of Information Act, came into effect in July 2020. It repeals the AIPPA. The Zimbabwean government has also commenced the process of revising the third law. In September 2024 the Cabinet adopted the Broadcasting Services Amendment Bill which will introduce changes to the Broadcasting Services Act.91

The steps taken by Zimbabwe to repeal or revise the impugned laws present another case of situational compliance. These steps, taken 15 years after the adoption of Resolution 89, were largely catalysed by the change of government and by more recent local and international pressure. For example, one of the possible recent local factors that contributed to the repeal of AIPPA was a recommendation by a government-sponsored Information and Media Panel of Inquiry.92 For the repeal of POSA, one of the immediate triggers was a 2018 domestic court judgment that declared a key provision of the Act unconstitutional.93 In Zimbabwe’s own admission to the Commission in its 2019 combined eleventh to fifteenth periodic report, another trigger was a recommendation from the Universal Periodic Review (UPR).94 It is important to note that despite the enactment of the new laws, repressive practices remain entrenched in Zimbabwe. According to Amnesty International, Mnangagwa’s administration has failed to break from the past and continues to use law as an instrument of oppression.95

4.2.2 Cases of non-compliance

Eritrea has not taken any concrete steps to implement Resolution 91 of 2005. The country’s immediate reaction to the resolution was to object to its publication as an integral part of the Commission’s nineteenth activity report. As a result, the AU Executive Council expunged the resolution from the report, as it did in the case of the resolutions concerning Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda and Zimbabwe after these had also raised objections.96 The Executive Council also gave Eritrea and the four other states a period of three months to file replies to those resolutions. All the concerned states, except for Eritrea, filed their replies.

With Eritrea failing to take the opportunity to respond to Resolution 91 as directed by the Executive Council, the African Commission did not receive a formal reply until 13 years later when the country submitted its initial state party report in 2018. In the report, Eritrea categorically denied that the 11 former government officials were political prisoners.97 It asserted that the claim that the 11 officials were detained because of exercising their freedom of expression is ‘factually unfounded and far from the truth’, and that their arrest was not arbitrary because it was duly sanctioned by the national assembly.98

Basically, the 11 former government officials remain incarcerated more than two decades after their arrest and detention without trial.99 Perhaps due to the long lapse of time, the African Commission did not reiterate the call for the release of the detainees in its 2018 Concluding Observations on Eritrea’s initial state party report. Instead, the Commission recommended that Eritrea should take measures to urgently address the denial of basic rights to all detained persons, including the former government officials.100

Eswatini has not complied with Resolution 216 of 2012 requiring it to implement the Commission’s decision in the case of Lawyers for Human Rights v Swaziland by amending or repealing the 1973 Proclamation. In 2005 Swaziland adopted a new Constitution, but it left the 1973 Proclamation intact. With the Proclamation continuing to exist side by side with the Constitution, the country’s executive, judicial and legislative powers still vest in the King. In terms of the Proclamation, political parties remain banned in Eswatini. Under the UPR, Eswatini has previously accepted recommendations to repeal the Proclamation but has yet to take actual steps in that regard.101

Eswatini has also not complied with Resolution 554 of 2023 calling for the release of MPs Mduduzi Bacede Mabuza and Mthandeni Dube. Barely two weeks after the adoption of the Resolution, the two MPs were convicted under the country’s terrorism and sedition laws for allegedly inciting unrest during the pro-democracy protests of June 2021. They were later sentenced to prison terms of 25 years and 18 years respectively. Human rights groups have condemned their convictions and sentences, with Amnesty International describing them as ‘unjust and baseless’.102 Eswatini has also taken no effective steps to investigate the killing of Thulani Maseko. In August 2023 the police stated that an investigation was progressing, but there has been no tangible proof of such an investigation.103

4.3 In-depth impact studies

In this part, the impact of the resolutions adopted in respect of The Gambia and Nigeria is examined in detail. These two countries allow for some level of comparison of state responses to similar kinds of criticism or pressure from the African Commission. The in-depth analysis of these two countries also allows for a closer scrutiny of the political, social and economic contexts in which compliance with the Commission’s country-specific resolutions takes place.

4.3.1 Nigeria

The 1990s was a period of severe repression in Nigeria. On 12 June 1993 Nigeria held presidential elections in order to transition the country from military to civilian rule. Despite the fact that the elections were free and fair according to observers, the military ruler at the time, General Ibrahim Babangida, nullified the results. He was later forced by domestic and international pressure to hand over power to a transitional government, but the new administration did not last long. Sani Abacha, the defence minister, took control in November 1993. Among his immediate actions upon seizing power was the abolition of habeas corpus procedures for political detainees and the suspension of the jurisdiction of courts in human rights matters.104 He installed an authoritarian regime that lasted until his death in office in June 1998.

Throughout the 1990s, the African Commission followed the events in Nigeria with keen interest. It published its first resolution on the country in November 1994 (Resolution 11),105 about a year into Abacha’s rule. Resolution 11 established the foundation of the Commission’s future engagement with the military regime. It was short, running to slightly more than half a page, but it carried a strong message. The resolution regretted the nullification of the 12 June 1993 elections and condemned the suspension of the application of the African Charter, the exclusion of military decrees from the jurisdiction of courts, disregard for court judgments, and unprocedural enactment of penal laws with retroactive effect. The resolution also condemned the closure of newspaper houses and the detention of pro-democracy activists and journalists.

Among those who had been detained by the Abacha regime was Ken Saro-Wiwa, an internationally-renowned Ogoni activist. He was detained in May 1994 together with other Ogoni community activists after a riot during which some Ogoni community leaders were killed. The resolution boldly called upon the military regime to ‘hand over the government to duly elected representatives of the people without unnecessary delay’. It also took a decision to send a delegation to the country in order to verbally express to the government its concerns about gross human rights violations and the need for urgent transfer of power to a civilian authority.

In March 1995, amidst strong opposition from Nigeria,106 the African Commission adopted another resolution on the situation of human rights in Nigeria (Resolution 16).107 Resolution 16 reiterated the concerns contained in Resolution 11 but went further and called upon the military government to ‘release all prisoners, reopen all closed media and respect freedom of the press, lift arbitrarily imposed travel restrictions, allow unfettered exercise of jurisdiction by the courts and remove all military tribunals from the judicial system’.

In early October 1995, Resolutions 11 and 16 had begun to bear some fruit when the military government sent a delegation to the Commission’s eighteenth ordinary session held in Praia, Cape Verde. At the session, the Nigerian delegation mounted a protest against the adoption of condemnatory resolutions against the country.108 The delegation argued that article 59 of the African Charter did not permit the African Commission to publish its resolutions before they are considered and adopted by the OAU Assembly of Heads of State and Government. In other words, the Commission had breached ‘article 59 confidentiality’ by publishing the resolutions as it did.

The African Commission rejected Nigeria’s argument, rightly observing that the adoption of resolutions does not fall under the purview of article 59.109 It clarified that article 59 falls under chapter III of the African Charter which deals with communications. Therefore, the Commission concluded that ‘[t]he resolution on Nigeria does not refer to communications in any way’ and that ‘[t]here is no bar on resolutions of the Commission being disseminated however the Commission sees fit’.110

Despite the fact that it objected to the adoption of Resolutions 11 and 16, the African Commission managed to obtain a concession from the Nigerian delegation. Specifically, the delegation extended an official invitation to the Commission to conduct a country visit to Nigeria in February 1996.111 However, the situation in Nigeria rapidly deteriorated after the conclusion of the Commission’s eighteenth ordinary session. On 31 October 1995, Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni activists were sentenced to death for incitement to murder following a trial that had been roundly condemned. In spite of a request from the African Commission to stay the executions,112 the nine were secretly hanged to death in November 1995. At the time the nine were executed, 19 other Ogoni activists (Ogoni 19) were standing trial on charges of murder.

In December 1995 the African Commission convened an extraordinary session in Kampala, Uganda, to specifically deliberate about the worsening situation in Nigeria. This served to pile more pressure on the military regime. As Murray observes, the session was crucial because of the publicity that it gave to the situation in Nigeria.113 Further concessions were obtained at the session. While lamenting that the country had been the subject of ‘slanderous campaigns’, Nigeria’s High Commissioner to Uganda emphasised ‘the will of the Nigerian government to cooperate with the Commission’.114 Once again, an official invitation was extended to the Commission to visit the country.115 The Commission also used the session to further push for the release of the Ogoni 19.116

The country visit did not take place in February 1996 as expected. It materialised a year later, in March 1997. The visit came as a pleasant surprise. The Commission’s delegation met various groups during the visit, including government officials, the national human rights institution, and a few of the Ogoni 19. However, it did not spend much time with representatives of NGOs, an oversight for which it was heavily criticised.117

Despite the delay in undertaking the mission, it is evident that Resolutions 11 and 16 contributed to the decision of the military government to allow the visit.118 According to Okafor,

the acceptance of this mission by the executive in Nigeria at a time when it was controlled by the army, is significant evidence of the proposition that the executive was clearly concerned to act in ways that pleased the Commission, in ways that might soften the Commission’s censure (however non-binding that was).119

In Okafor’s words lie the true motive of the military government. It allowed the country visit so as to soften international pressure; it had no immediate interest in changing its repressive practices. The military government used the visit to depict itself as an internationally-cooperative regime. It also used the visit to counter pressure for it to allow country visits by UN thematic rapporteurs.120

The Ogoni 19 were not released from detention until September 1998 when General Abdulsalami Abubakar took over the reins of power following the death of Abacha. In October 1998 the African Commission adopted a resolution on Nigeria that welcomed ‘the positive evolution in the field of human rights, the promises and democratic advances made by the Nigerian government since the end of June 1998’.121 The resolution also praised the release of the Ogoni 19.

There are those who partly attribute their release to the pressure exerted on the Nigerian government by the African Commission through its resolutions (and other mechanisms).122 While there is little doubt that the military regime cared about the Commission’s criticism of its human rights record, an accurate assessment is that the release of the Ogoni 19 amounted to situational compliance with Resolutions 11 and 16.

It is also important to bear in mind that Resolutions 11 and 16 did not work in isolation. The resolutions were part of a large global campaign involving both coercive sanctions and naming and shaming. The major actors included the United States of America (USA), the United Kingdom (UK), the UN, the European Union (EU), the Commonwealth, and international non-governmental organisations (INGOs).123 Pressure was also mounted from within Nigeria such that the government was targeted from above and below. Indeed, the Commission adopted Resolutions 11 and 16 after intense lobbying by Nigerian NGOs.124 These NGOs also filed numerous cases against Nigeria before the African Commission, piling pressure on the government to change its practices.125

After 1998, African Commission resolutions on Nigeria have been few and far between. In response to ethnic and religious violence in the northern part of Nigeria in 2004, the Commission adopted Resolution 70 condemning attacks against civilians and urging the government to ‘bring the perpetrators of any human rights violations to justice, and to compensate victims and their families’. With an active conflict in North-Eastern Nigeria since 2009, the Commission’s resolutions on Nigeria in the last 15 years have largely focused on violations and abuses committed in that conflict, primarily by the armed group Boko Haram. These resolutions have not received much publicity and evidence of their impact is relatively difficult to assess.

4.4 The Gambia

The Gambia has a special and sentimental connection with the African Commission. The bulk of negotiations leading to the adoption of the African Charter took place in Banjul, The Gambia’s capital city, with the country’s President at the time, Dawada Jawara, playing a central role in facilitating the process. Banjul is also the Commission’s seat or headquarters. It started operating out of Banjul in June 1989, and for about five years it enjoyed a cordial relationship with the host country. The Commission routinely praised The Gambia for its impressive human rights record and treated it with noticeable deference.126 However, the Commission’s relationship with the host country dramatically changed in July 1994 when Jawara’s government was toppled in a military coup. The coup’s ringleader, Yahya Jammeh, took over control of the government and subsequently announced that elections would be held after a transitional period of four years.

Meeting in Banjul in October 1994, the African Commission adopted Resolution 13 on the situation in The Gambia.127 It contained scathing criticism of the coup, describing it as ‘a clear setback to the cause of democracy’ and a ‘flagrant and grave violation of the right of the Gambian people to freely choose their government’. It called upon the military government to transfer power to the ‘freely-elected representatives of the people’. It also requested the government to ensure that (a) the Bill of Rights contained in the Gambian Constitution remains supreme; (b) the independence of the judiciary is respected; (c) the rule of law, as well as the recognised international standards of fair trial and treatment of persons in custody are observed; and (d) all individuals detained during or in the aftermath of the coup are either charged with an offence or released.

Although the military government subsequently reduced the transitional period from four to two years, the human rights situation in The Gambia did not improve following the adoption of Resolution 13. Instead, it worsened. In March 1995 the African Commission adopted another resolution on the situation in The Gambia (Resolution 17).128 The content of the resolution suggests that somehow the Commission had by this time surrendered to the fact that the military government would be there to stay. Although it expressed ‘great concern’ about reports of serious allegations of human rights and called on the government to set up an independent commission of inquiry to investigate the allegations, the Commission recommended that the economic sanctions imposed on the country be lifted.129 It premised this recommendation on the fact that the government had announced a reduction of the transitional period.

In Resolution 17 the African Commission reduced rather than increased the pressure on the Gambian government. The global spotlight on the country also subsided with time, giving Jammeh the time to entrench authoritarian rule. A state of fear permeated the country in his more than two decades of autocratic leadership.130 Intimidation and crackdown on critics and opposition leaders, extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances and torture became routine in the country. These violations intensified after an attempted coup d’état in March 2006, in the aftermath of which at least 63 suspected coup plotters and perceived government opponents were arrested.131 Later that year a prominent journalist, Chief Ebrima Manneh, and an opposition supporter, Kanyiba Kanyie, were arrested by state security forces. The two went missing after they were arrested. The government denied that they were in state custody. In June 2008 the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Court of Justice dismissed the claim that Chief Ebrimah was not in state custody and ordered his release.132

In November 2008 the African Commission adopted a resolution on The Gambia (Resolution 134) expressing deep concern for and condemning the ‘severe deterioration’ of the human rights situation in the country.133 The resolution accused The Gambia’s state security forces for unlawful arrests and detentions, torture, extra-judicial killings and enforced disappearances. The resolution made a specific call for the immediate release of Chief Ebrima and Kanyie Kanyiba in compliance with the judgment of the ECOWAS Court of Justice. Rather than improving, the human rights situation in the country deteriorated. On 21 September 2009 President Jammeh threatened to kill human rights defenders whom he claimed were sabotaging and destabilising his government.134

The African Commission swiftly adopted a strongly-worded resolution (Resolution 145) in which it observed that President Jammeh’s utterances had implications for the safety of the members and staff of the Commission as well as for the participants of the Commission’s forty-sixth ordinary session, which was scheduled to take place in Banjul in November that year.135 The demands in Resolution 145 arguably are the boldest that the Commission has ever made in a country-specific resolution. They are worth repeating here in full:

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Calls on the African Union to intervene with immediate effect to ensure that HE President Sheikh Professor Alhaji Dr Yahya AJJ Jammeh withdraws the threats made in his statement;

- Further calls on the African Union to ensure that the Republic of The Gambia guarantees the safety and security of the members and staff of the African Commission, human rights defenders, including journalists in The Gambia, and all participants in the activities of the African Commission taking place in The Gambia;

- Requests the African Union to authorise and provide extra-budgetary resources to the African Commission to ensure that the 46th ordinary session is convened and held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, or any other member state of the African Union, in the event that His Excellency the President of the Republic of The Gambia does not withdraw his threats and the government cannot guarantee the safety and security of the members and staff of the African Commission and the participants of the 46th ordinary session;

- Requests the African Union to consider relocating the Secretariat of the African Commission in the event that the human rights situation in the Republic of The Gambia does not improve;

- Urges the government of the Republic of The Gambia to implement the recommendations of its previous Resolutions, in particular, Resolution No ACHPR/Res. 134(XXXXIV)2008, adopted during the 44th ordinary session held in Abuja, Nigeria, from 10 to 24 November 2008, and to investigate the disappearance and/or killing of prominent journalists Deyda Hydara and Ebrima Chief Manneh.

In addition to adopting the resolution, the Commission sent a letter to the Gambian government and published a press release that contained the text of the resolution.136 Immediately after the adoption of Resolution 145, the Gambian government responded with mixed sentiments. On the one hand, it emphasised that it was committed to human rights and to host the forty-sixth ordinary session of the Commission.137 On the other hand, it launched an attack on the Commission and the African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights Studies (ACDHRS), a Banjul-based NGO, which it believed had lobbied for the adoption of Resolution 145.138

It threatened to review its relationship with the ACDHRS and described Resolution 145 as ‘obnoxious and based on ulterior motives’, and questioned the reasons for its adoption ‘in a meeting held outside The Gambia’.139

Resolution 145 definitely raised the costs for The Gambia. The pressure eventually yielded positive results when a high-level Gambian delegation, comprising the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Justice and Interior, held a meeting with the then Acting Chairperson of the African Commission together with Jean Ping, who at the time was the Chairperson of the AU Commission.140 In the meeting, the Gambian delegation assured the Commission that participants of the forty-sixth ordinary session would be safe and entitled to freely express themselves during the session.141 The session eventually took place in Banjul without any incident.

That The Gambia softened its extreme stand was also a function of human rights pressures emanating from other sources. A number of NGOs issued press releases in support of Resolution 145 and declared that they would not attend the Commission’s forty-sixth ordinary session unless President Jammeh withdrew his threat.142 Two UN Special Rapporteurs sent a joint letter of appeal to the Gambian government demanding that it guarantees the safety of human rights defenders.143 Resolution 145 shows how the Commission’s country-specific resolutions may impact on state behaviour if the Commission simultaneously deploys a number of mechanisms available to it. Resolution 145 was followed by an urgent appeal, a press release, and diplomacy.

In pledging to ensure the safety of human rights defenders, The Gambia made a tactical concession that cooled down the pressure. When it ceased to be in the spotlight, it resumed its repressive practices. In the years following the adoption of Resolution 145, the human rights situation in The Gambia worsened, prompting the African Commission to adopt further resolutions on the country,144 and other regional and international actors to renew their human rights pressures on The Gambia. The landscape of human rights in the country eventually changed when President Jammeh lost the December 2016 election to Adama Barrow.

5 Conclusion

This article sought to analyse the impact of these African Commission’s country-specific resolutions using a theoretical framework premised on the concept and practice of naming and shaming or human rights criticism. On face value, it is possible to dismiss naming and shaming as cheap talk. However, studies reflecting on the utility of naming and shaming have shown that it does affect state behaviour. Naming and shaming may directly influence human rights conduct by raising the stakes for the target country. Alternatively, naming and shaming may elicit a discursive response from the target country setting in motion a socialisation process that may ultimately lead to changes in the conduct of the state.

If it were possible to look at the impact of the African Commission’s country-specific resolutions from an aerial or bird’s eye view, what picture would one see? As expected, the size of the impact will depend on one’s distance from the ground. From thousands of feet up in the sky, the impact will appear minute and inconsequential. Closer to the ground, the impact will look big and enormous. In actual terms, this means that at a macro-level, it may appear that the Commission has shone a spotlight on many countries to no apparent effect. Consider the two case studies of direct impact analysed in this article.

The African Commission named and shamed Abacha’s regime in Nigeria, but human rights violations continued unabated until the end of his reign. For The Gambia, the Commission raised the stakes by recommending the relocation of its headquarters from the country, but human rights violations persisted and intensified over the next few years. From a micro-level, the Commission’s country-specific resolutions have inspired tentative actions which are no small achievements considering the environment in which those actions came about. The decision of the Abacha government to allow the Commission to visit Nigeria and The Gambia’s guarantee of safety to participants of the Commission’s forty-sixth ordinary session are examples of successes worth cherishing. In other instances, such as in Ethiopia, Kenya and Zimbabwe, this article presents evidence of situational compliance with the Commission’s country-specific resolutions. The challenge for the Commission is to move the impact of its country-specific resolutions from tentative actions or cases of situational compliance to macro-level changes in state practices.

-

1 Urgent appeals play a similar role to ‘provisional measures’ that the Commission issues in the context of its communications procedure. See Rules of Procedure of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights 2020, Rule 100.

-

2 For recent press releases by the African Commission, see News | African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (accessed 12 November 2024).

-

3 The Commission normally holds four ordinary sessions in a year, two of which are open for public participation. The sessions often take place in February/March, April/May, July/August and October/November. The inter-session periods are the months in between the ordinary sessions.

-

4 Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are specifically and globally known for their naming and shaming campaigns. See S Hopgood Keepers of the flame: Understanding Amnesty International (2006); K Roth ‘Defending economic, social and cultural rights: Practical issues faced by an international human rights organisation’ (2004) 26 Human Rights Quarterly 63.

-

5 J Meernik and others ‘The impact of human rights organisations on naming and shaming campaigns’ (2012) 56 Journal of Conflict Resolution 233. See also J Franklin ‘Shame on you: The impact of human rights criticism on political repression in Latin America (2008) 52 International Studies Quarterly 187 (describing naming and shaming as ‘the most commonly used weapon in the arsenal of human rights proponents’); Roth (n 4) 63 (describing naming and shaming as ‘the core methodology’ of Human Rights Watch).

-

6 See T Piccone & N McMillen ‘Country-specific scrutiny at the United Nations Human Rights Council: More than meets the eye’ (accessed 13 November 2024).

-

7 For an analytical overview of the CHR’s country-specific resolutions, see M Lempinen The United Nations Commission on Human Rights and the different treatment of governments: An inseparable part of promoting and encouraging respect for human rights (2005) 193-221.

-

8 On the role and value of these reports, see T Farer ‘The future of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights: Promotion vs exposure’ in J Mendez & F Cox (eds) The future of the inter-American human rights system (1998) 515.

-

9 See T Farer ‘The rise of the Inter-American human rights regime: No longer a unicorn, not yet an ox’ (1997) 19 Human Rights Quarterly 510, 512.

-

10 See generally Report of the Secretary-General ‘In larger freedom: Towards development and human rights for all’ UN Doc A/49/2005, 21 March 2005.

-

11 J Lebovic & E Voeten ‘The politics of shame: The condemnation of country human rights practices in the UNCHR’ (2006) 50 International Studies Quarterly 861.

-

12 J Lebovic & E Voeten ‘The cost of shame: International organisations and foreign aid in the punishing of human rights violators’ (2009) 46 Journal of Peace Research 79.

-

13 W Cole ‘Institutionalising shame: The effect of Human Rights Committee rulings on abuse, 1987-2007’ (2012) 41 Social Science Research 539.

-

14 T Piccone ‘The contribution of the UN’s special procedures to national level implementation of human rights norms’ (2011) 15 International Journal of Human Rights 206.

-

15 R Goldman ‘History and action: The Inter-American human rights system and the role of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ (2009) 31 Human Rights Quarterly 856; Farer (n 9).

-

16 Goldman (n 15) 873.

-

17 For a very brief analysis of the indirect impact of a select number of the Commission’s country-specific resolutions, see F Viljoen International human rights law in Africa (2012) 380-382; for a more comprehensive view, see J Biegon ‘The impact of the resolutions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ unpublished LLD thesis, University of Pretoria, 2016 (on file with author).

-

18 K Kinzelbach & J Lehmann Can shaming promote human rights? Publicity in human rights foreign policy: A review and discussion paper (2015) 5.

-

19 F Ouguergouz The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights: A comprehensive agenda for human dignity and sustainable democracy in Africa (2003) 549.

-

20 Resolution on Nigeria’s Return to a Democratic System, ACHPR/Res.28(XXIV)98 adopted at the 24th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 22-30 October 1998.

-

21 Ouguergouz (n 19) 544.

-

22 See Resolution on the Prevention of Women and Child Trafficking in South Africa during the 2010 World Cup Tournament, ACHPR/Res.165(XLVII)10 adopted at the 47th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 12-26 May 2010.

-

23 See Resolution on the Human Rights Situation in Eritrea, ACHPR/Res.91(XXXVIII)05 adopted at the 38th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 21 November-

5 December 2005; Resolution Calling on the Republic of Kenya to Implement the Endorois Decision, ACHPR/Res.257(2013) adopted at the 54th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 22 October-5 November 2013; Resolution on the Human Rights Situation in the Kingdom of Swaziland, ACHPR/Res.216(LI)2012 adopted at the 51st ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 18 April-2 May 2012. -

24 Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in Tunisia, ACHPR/Res.56(XXIX)01 adopted at the 29th ordinary session, Tripoli, Libya, 23 April-

7 May 2001. -

25 Resolution on the Attacks against Journalists and Media Practitioners in Somalia, ACHPR/Res.221(LI)2012 adopted at the 51st ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 18 April-2 May 2012.

-

26 Resolution on the Crimes Committed against Women in the Democratic Republic of Congo, ACHPR/Res.173(XLVIII)10 adopted at the 48th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 10-24 November 2010.

-

27 Viljoen (n 17) 380.

-

28 For the list of non-compliant states, see ‘Paper on the status of submission of periodic reports by states parties to the Charter’ African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 81st ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 17 October to

6 November 2024 (on file with author). -

29 Resolution on the Establishment of a Resolutions Committee, ACHPR/Res.338 (LVIII) 2016 adopted at the 58th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia,

6-20 April 2016. -

30 See Resolution on the Situation in Palestine and the Occupied Territories, ACHPR/Res.48(XXVIII)00 adopted at the 28th ordinary session, Cotonou, Benin, 26 October-6 November 2000; Resolution on the Situation in Palestine and the Occupied Territories adopted at the 81st ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 17 October-6 November 2024.

-

31 Omnibus resolutions and the resolutions on Palestine were not included in the count used to generate the table.

-

32 Resolution on Human Rights in Conflict Situations, ACHPR/Res.332 (EXT.OS/XIX) 2016 adopted at the 19th extraordinary session, The Gambia,

16-25 February 2016. -

33 See R Murray ‘Serious or massive violations under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights: A comparison with the Inter-American and European mechanisms’ (1999) 17 Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 109, 126-127.

-

34 See F Viljoen ‘The relationship between international human rights and humanitarian law in the African human rights system: An institutional approach’ in E de Wet & J Kleffner (eds) Convergence and conflicts of human rights and international humanitarian law in military operations (2014) 303.

-

35 A Clark ‘The normative context of human rights criticism: Treaty ratification and UN mechanisms’ in T Risse and others (eds) The persistent power of human rights: From commitment to compliance (2013) 125, 126.

-

36 D Hawkins International human rights and authoritarian rule in Chile (2002) 20.

-

37 Franklin (n 5) 189.

-

38 A Brysk ‘From above and below: Social movements, the international system, and human rights in Argentina’ (1993) 26 Comparative Political Studies 259, 273.

-

39 K Raustiala & A Slaughter ‘International law, international relations and compliance’ in W Carlsnaes, T Risse & B Simmons (eds) Handbook of international relations (2002) 538, 539.

-

40 As above.

-

41 F Viljoen & L Louw ‘State compliance with the recommendations of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1994-2004’ (2007) 101 American Journal of International Law 5.

-

42 For examples of studies that use this logic to analyse impact, see European Inter-University Centre for Human Rights and Democratisation Beyond activism: The impact of the resolutions and other activities of the European Parliament in the field of human rights outside the European Union (2006); M O’Flaherty & J Fisher ‘Sexual orientation, gender identity and international human rights law: Contextualising the Yogyakarta principles’ (2008) 8 Human Rights Law Review 207.

-

43 S Cohen ‘Government responses to human rights reports: Claims, denials and counterclaims’ (1996) 18 Human Rights Quarterly 517.

-

44 As above.

-

45 For detailed elaboration of the concept of rhetorical entrapment, see F Shimmelfennig ‘The community trap: Liberal norms, rhetorical action, and the Eastern Enlargement of the European Union’ (2001) 55 International Organisation 47.

-

46 T Risse & K Sikkink ‘The socialisation of international human rights norms into domestic practices: Introduction’ in T Risse and others (eds) The persistent power of human rights: From commitment to compliance (2013) 23.

-

47 See generally Risse and others (n 46).

-

48 H Schmitz ‘Transnational activism and political change in Kenya and Uganda’ in Risse and others (n 46) 39.

-

49 S Granzer ‘Changing discourse: Transnational advocacy networks in Tunisia and Morocco’ in Risse and others (n 46) 109; V Hullen ‘The “Arab Spring” and the spiral model: Tunisia and Morocco’ in Risse and others (n 46) 182.

-

50 D Black ‘The long and winding road: International norms and domestic political change in South Africa’ in Risse and others (n 46) 78.

-

51 Granzer (n 49); Hullen (n 49).

-

52 Schmitz (n 48).

-

53 S Katzenstein ‘Reverse-rhetorical entrapment: Shaming and naming as a two-way street’ (2013) 46 Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 1079.

-

54 Biegon (n 17).

-

55 T Kamminga ‘The thematic procedures of the UN Commission on Human Rights’ (1987) 34 Netherlands International Law Review 299, 317.

-

56 F Viljoen ‘State compliance with the recommendations of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ in M Baderin (ed) International human rights law: Six decades after the UDHR and beyond (2020) 411, 426.

-

57 See, eg, Lempinen (n 7) 193-196.

-

58 A Abbas ‘Refugees and displaced people in Africa: An interview with commissioner Bahame Tom Mukirya Nyanduga, Special Rapporteur on Refugees and Displaced Persons in Africa’ in H Abbas (ed) Africa’s long road to rights: Reflections on the 20th anniversary of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (2007) 37, 48.

-

59 Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights in Africa, ACHPR/Res.14(XVI)94 adopted at the 16th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 25 October-

3 November 1994; Resolution on the Human Rights Situation in Africa, ACHPR/Res.40(XXVI)99 adopted at the 26th ordinary session, Kigali, Rwanda,

1-15 November 1999; Resolution on the General Human Rights in Africa, ACHPR/Res.157(XLVI)09 adopted at the 46th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia,

11-25 November 2009; Resolution on the General Human Rights Situation in Africa, ACHPR/Res.207(L)11 adopted at the 50th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 24 October-5 November 2011. -

60 Resolution on Nigeria’s Return to a Democratic System, ACHPR/Res.28(XXIV)98 adopted at the 24th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 22-30 October 1998.

-

61 Resolution on Compliance and Immediate Implementation of the Arusha Peace Agreement for Burundi, ACHPR/Res.49(XXVIII)00 adopted at the 28th ordinary session, Cotonou, Benin, 23 October-6 November 2000.

-

62 Resolution on the Peace Process in Guinea Bissau, ACHPR/Res.32(XXIV)98 adopted at the 24th ordinary session, 22-31 October 1998.

-

63 Resolution Concerning the Republic of Seychelles’ Refusal to Present its Initial Report, ACHPR/Res.39(XXV)99 adopted at the 25th ordinary session, 26 April-

5 May 1999. -

64 Resolution on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in Tunisia, ACHPR/Res.56(XXIX)01 adopted at the 29th ordinary session, Tripoli, Libya, 23 April-

7 May 2001; Resolution on the Human Rights Situation in the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, ACHPR/Res.340 (LVIII) 2016 adopted at the 58th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 6-20 April 2016. -

65 Resolution on the Human Rights Situation in Niger, ACHPR/Res.478 (LXVIII) 2021 adopted at the 68th ordinary session, virtual, 14 April-4 May 2021.

-

66 Resolution on the Impact of Sanctions on the Realisation of Human Rights in Zimbabwe, ACHPR/Res.610 (LXXXI) 2004 adopted at the 81st ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 17 October-6 November 2024.

-

67 See, eg, Resolution on the Human Rights Situation in Côte d’Ivoire, ACHPR/Res.182(EXT.OS/IX)11 adopted at the 9th extraordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 23 February-3 March 2011 (urging Côte d’Ivoire to ‘work towards the restoration of peace and security’).

-

68 See, eg, Resolution on Nigeria, ACHPR/Res.70(XXXV)04 adopted at the 35th ordinary session, Banjul, The Gambia, 21 May-4 June 2004 (asking the Nigerian government to ‘bring perpetrators of any human rights violations to justice’).

-