Chairman Okoloise

BL (Nigerian Law School) LLB (Ambrose Alli) LLM (Pretoria)

Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Jurisprudence, College of Law, University of South Africa

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1400-649X

Profound gratitude is given to mentors at the UNISA College of Law, Prof Anél Ferreira-Snyman and Prof Jan-Harm de Villiers, for their invaluable feedback and insightful suggestions on the initial draft, which have greatly enhanced the quality of this article. Also, due acknowledgment is given to Ms Aouatef Mahjoub, the legal officer supporting the Working Group on Implementation of Decisions (WGID) of the African Children’s Committee, for facilitating access to resources used in the further analysis on the WGID.

Edition: AHRLJ Volume 24 No 2 2024

Pages: 985 - 1016

Citation: C Okoloise ‘Systematising monitoring: The case for a special mechanism for following up on the implementation of decisions by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ (2024) 24 African Human Rights Law Journal 985-1016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2024/v24n2a23

Download article in PDF

Summary

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has, since its inauguration on 2 November 1987, struggled to follow up on the implementation of its decisions and recommendations. Despite having received roughly 133 state reports and approximately 900 communications, only about two-thirds of these are estimated to have been considered and determined. Due to several setbacks, including budgetary considerations, understaffing and a backlog of pending cases, the Commission’s mandate to ensure the protection of human and peoples’ rights and interpret the provisions of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights is often complicated by the continental scope and complexity of its equally-important mandate to promote human and peoples’ rights. As if these challenges were not enough, the Commission is continuously overwhelmed by the responsibility not only to convene its ordinary sessions four times a year during which it considers state reports and contentious cases submitted to it, but also to ensure that its decisions are implemented by the state parties concerned. To offset the imbalance foisted by these responsibilities against the multifaceted human rights challenges pertaining to individuals, marginalised and vulnerable groups and particular human rights themes, the Commission created special mechanisms. However, after more than four and a half decades, the Commission is yet unable to address – in a systematic way – the growing spate of non-compliance by state parties with its decisions and recommendations. This article, therefore, seeks to articulate that the growing volume of non-implemented decisions and recommendations has reached a critical point, necessitating the establishment of a special mechanism dedicated to the follow-up and implementation of its decisions and recommendations handed down in contentious and non-contentious cases. The article adopts an institutional approach in making the case that a dedicated special mechanism has become a necessity for enabling the Commission to routinely and systematically follow up, track and better monitor state party compliance with its decisions. The article finds that such a special mechanism will aid the Commission to better engage state parties on their obligations under the African Charter and consistently report on its implementation mandate.

Key words: special mechanism; implementation; decision; recommendations; African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

1 Introduction

The decisions and recommendations of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Commission) would be meaningless if domestic implementation is unmonitored. The decisions and recommendations of the African Commission are the inferences and propositions reached on state party reports, individual and inter-state communications, the reports on country or thematic human rights issues and missions, resolutions, and other instruments adopted by the African Commission. Under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter), the African Commission is the primary treaty body responsible for monitoring the implementation of the provisions of the African Charter.1 Its mandate is broad, comprising the following elements: the promotion of human and peoples’ rights; ensuring the protection of human and peoples’ rights in Africa; and interpretation of the provisions of the African Charter.

The African Commission’s mandate to promote human and peoples’ rights requires the performance of an extensive list of functions. This includes the responsibility to receive and analyse documents; undertake studies and research on human and peoples’ rights challenges in Africa; organise conferences, seminars and symposiums; disseminate information; inspire national human rights institutions (NHRIs) and local organisations; and give guidance to states on the domestic implementation of their obligations under the African Charter.2 As part of its function to promote human and peoples’ rights under article 45(1)(a) of the African Charter, the African Commission is empowered to formulate and prescribe principles and rules targeted at solving legal issues pertaining to human and peoples’ rights that should influence domestic legislation in African countries. The promotion mandate also requires the Commission to cooperate with other African and international institutions working in the field of human and peoples’ rights. Additional to the extensive bandwagon of promotion functions of the Commission is the mandate to ensure the protection of human and peoples’ rights in Africa and interpret the provisions of the African Charter. The choice of the phrase ‘ensure the protection of human and peoples’ rights’ rather than ‘protect human and peoples’ rights’, as used in the Africa Charter, is particularly instructive. It is instructive in that it presupposes that the responsibility to protect human and peoples’ rights ultimately is that of states. This is because, at the inception of the African Charter, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), now the African Union (AU), did not consider that ‘the protection of human rights has been regarded as an overriding consideration’.3

The African Commission’s broad mandate to promote and protect human rights is fortified by the imperative of state action. On the one hand, the promotion of human and peoples’ rights requires the African Commission to ‘collect’ information on the situation of human rights in a state and ‘give its views or make recommendations to governments’.4 This responsibility is reinforced by the obligation of state parties to submit periodic reports to the Commission on the respective measures that they have adopted to give effect to the rights and freedoms enshrined in the African Charter.5 On the other hand, ensuring the protection of human and peoples’ rights requires the Commission to receive, consider and determine complaints alleging violations of the provisions of the African Charter by a state party concerned. After consideration of the reports and complaints submitted to it, the Commission presents its findings and recommendations for domestic implementation.

This article seeks to address the widespread concern among scholars of the African human rights system that the (in)effectiveness of the Commission’s monitoring role has reached a critical point necessitating the establishment of a special mechanism for following up on the implementation of its findings and recommendations to states.6 Murray and others argue that while some measures have been taken previously by the Commission to establish processes to monitor the implementation of decisions, the role assigned in doing so ‘is confused’ and does little to capitalise on their institutional strengths.7 Utilising an institutional approach, I argue that for the African Commission to effectively monitor domestic implementation, it needs to have in place an appropriate and well-coordinated system for following up on the implementation of its findings and commendations. Follow-up, in this article, refers to the process by which the Commission methodically monitors and seeks information on the steps taken by a state party after the delivery of its findings and recommendations.8

An often-repeated criticism against the African Commission’s weak supervisory role is its lack of an enforcement mechanism to track implementation at the domestic level.9 Some scholars argue that to ensure domestic compliance, clear monitoring processes are necessary for better implementation outcomes.10 Strangely, since inception to date, the African Commission is yet to systematise its processes for following up on domestic implementation by states. In the recent past and currently, it has had to embellish this task within the framework of ‘commissioners’ promotion activities to the states parties concerned’11 pursuant to the 2010 and, subsequently, the 2020 Rules of Procedure. In other words, the Commission’s main point of engaging with follow-up activities has been during its promotion and fact-finding missions to the territories of state parties. The Commission has also had to adopt the haphazard approach of occasionally convening regional conferences on the implementation of its decisions and recommendations.12 Such ad hoc activities trivialise the high stakes associated with engaging states on their implementation of the Commission’s decisions and recommendations, which an institutionalised follow-up mechanism would better address.

The institutional approach to follow-up proposes that for the Commission to achieve a measurable and evidence-based system of domestic implementation of its decisions and recommendations, it is imperative to establish within the Commission’s internal processes a dedicated mechanism for that purpose. I make this proposal for several reasons. First, as Murray and Mottershaw argue, ‘national mechanisms cannot be the only approach to follow up and implementation’.13 An institutionalised mechanism will help to effectively coordinate the Commission’s engagement with national authorities in a way that keeps track of the nature and scope of domestic implementation of its findings and propositions. While states’ perceptions remain a critical neutralising factor fuelling non-implementation and non-compliance with Commission decisions domestically, the outright lack of a well-directed system of bureaucratically and diplomatically engaging states on the Commission’s end may have deepened state reticence. Second, a coordinated consideration of how states implement the Commission’s decisions and recommendations will assist the Commission with a feedback loop that informs the practicality and impact of such recommendations on the ground. Third, a systematised internal process of monitoring will afford the Commission an opportunity to frequently assess state party implementation and compliance and receive periodic inter-session activity reporting from the proposed follow-up mechanism, which is a practice that is not currently in place. More importantly, Rule 25 of the Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 makes this proposal workable because it allows the Commission to establish a special mechanism that will ‘present a report on its work to the Commission at each ordinary session’.14

In undertaking this analysis, the article adopts a five-part structure to justify the call for the immediate establishment of a special mechanism responsible for follow-ups. This introductory part has set the scene for the Commission to consider adopting an institutional approach to better monitor state implementation of its conclusions and recommendations. The next part considers the current challenges associated with implementing the Commission’s decisions and recommendations. The third part vindicates the necessity for a special mechanism for follow-up. The fourth part, thereafter, considers the role of the proposed special mechanism, while the final part summarises and concludes the analysis.

2 Current challenges in implementing the African Commission’s decisions

The effectiveness of the treaty-monitoring role of the African

Commission significantly rests not on the loudness of its proclamations, but on the respect and seriousness that state parties to the African Charter ascribe to its views and suggestions.15 Handing down decisions and recommendations for compliance without necessarily monitoring domestic implementation by state parties weakens the guiding authority of the African Commission to subsequently give decisions and recommendations to governments.16 In this part I consider the various factors militating against the domestic implementation of the Commission’s decisions and recommendations.

2.1 The deficit of systematically monitoring domestic implementation

For the almost four decades of its establishment, the African Commission has barely been able to keep up with the task of tracking the status of implementation of its decisions and recommendations. Attempts to justify the reasons for the seemingly weak monitoring of how its findings are implemented have often been attributed to a number of drawbacks, which I will deal with very briefly.

First, the equivocal phrasing of the substantive provisions of the African Charter text itself, including the provision of ‘claw-back’ clauses17 and the quasi-judicial character of the African Commission, seem to allow states some leg room to consider whether or not to implement the Commission’s determinations.18 This textual deficit and absence of any express wording mandating the Commission to follow up beyond the periodic reporting requirements under the African Charter and its supplementary protocols suggest that domestic enforcement of the Commission’s decisions and recommendations is at the discretion of relevant national authorities.19 The lack of an express provision in the African Charter conferring on the Commission the authority to monitor domestic implementation may have left the Commission hanging as to the intendments of the drafters and created an enduring puzzle on whether it can constitutionally formalise the follow-up process without attracting a punchy backlash from states. Viljoen argues that despite the absence of any express wording, the African Charter ‘implicitly allows for and, in fact requires, follow-up’.20

Second, beyond the textual limits of the African Charter, the African Commission was initially not sufficiently proactive in taking advantage of the opportunity it has to make its own rules for monitoring domestic implementation. Under the African Charter, the Commission is empowered to ‘lay down its rules of procedure’.21 On the strength of this provision, it has over the years enacted a number of procedural rules to guide the execution of its treaty mandate. However, until the 2010 revision of the Commission’s Rules of Procedure, ‘there was no institutionalised procedure to follow up on decisions’.22 A careful look at the historical iteration of the Commission’s rules will reveal that earlier versions of the Rules made no provision for following up on implementation. For instance, the Commission adopted its first Rules of Procedure on 13 February 1988, pursuant to article 42(2) of the African Charter.23 The 1988 Rules of Procedure were subsequently revised in 1995, which led to the adoption of the Rules of Procedure on 6 October 1995.24 Even this subsequent revision, about a decade after the Commission’s establishment, did not feature any transformative provision for monitoring states’ implementation of its decisions and recommendations through an institutionalised process.

The omission in the Commission’s Rules in respect of a formalised follow-up system was subsequently partly addressed, with the adoption of an improved version of the Rules of Procedure in 2010 and 2020, respectively.25 I say ‘partly’ because the provision for follow-up in these subsequent Rules of Procedure merely formally stipulated a process for following up on domestic implementation. They did not seek to establish a dedicated mechanism within the internal processes of the Commission to undertake the follow up of states’ implementation of the findings and recommendations contained in the Commission’s Concluding Observations and decisions on contentious cases.26 Under Rules 78, 90 and 112 of the Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2010 respectively, the Commission took the first step to prescribe its procedural processes for monitoring domestic implementation of its Concluding Observations, on the one hand, and decisions on cases settled amicably or determined on the merit, on the other.

With regard to Concluding Observations, Rule 78(2) of the 2010 Rules of Procedure required members of the Commission to ‘ensure the follow-up on the implementation of the recommendations from the Concluding Observations within the framework of their promotion activities to the states parties concerned’. A main consequence of the obligation under this Rule is this: Unless promotion activities such as convening the ordinary sessions of the Commission or conducting thematic activities and meetings, country visits or missions to the territory of a state party were undertaken by the Commission, commissioners or the Commission did not have to undertake follow-up actions with states. In other words, Rule 78(2) of the 2010 Rules of Procedure did not create an institutional mechanism for conducting follow-up actions in the absence of any formal convenings or promotion activities to state parties.

Remarkably, Rule 78(2) of the 2010 Rules of Procedure is largely retained in Rule 83(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020.27 However, though similarly worded, Rule 83(2) goes a step further by providing that ‘members [of the Commission] may request or take into account contributions by interested parties or invited institutions, on the extent to which those recommendations have been implemented’. This addition to the original wording of Rule 78(2) of the 2010 Rules of Procedure in Rule 83(2) of the 2020 Rules of Procedure takes into consideration the importance of infusing the opinions and support of civil society organisations (CSOs) in the process of monitoring domestic implementation of the Concluding Observations and recommendations made by the African Commission after the consideration of state party reports. Unfortunately, it does no more than that. The improved Rule 83(2) of the 2020 Rules also does not create a dedicated mechanism for monitoring domestic implementation when no sessions are convened, or missions undertaken to the territory of state parties.

With regard to cases (communications) submitted before the African Commission, follow-up actions are mandated by the post-2010 Rules of Procedure in respect of two categories of cases: cases resolved amicably, and cases decided on the merit. With respect to the first category, Rule 90 of the 2010 Rules of Procedure made provision for follow up on complaints resolved through the parties’ amicable settlement. Specifically, Rule 90(8) required the Commission, acting through the commissioner rapporteur of a communication,28 to undertake follow up and report on monitoring the implementation of the terms of the settlement agreement to each subsequent ordinary session of the Commission until the settlement is concluded. Such a report was to subsequently form part of the Activity Report of the Commission to the AU Assembly.

The provision of the 2010 Rules of Procedure on monitoring the implementation of amicable settlements is revised in the 2020 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission. Rule 112(7) of the 2020 Rules of Procedure provides that ‘[t]he Commission’s confirmation of a settlement shall be regarded as a decision requiring implementation and related follow-up for the purposes of these Rules’. However, unlike the 2010 Rules that required follow-up of implementation of the Settlement Agreement by the commissioner rapporteur responsible for the communication concerned, the 2020 Rules does not expressly impose that responsibility on the rapporteur.29 This leaves to conjecture whether it can be nevertheless implied because sub-Rule (3) provides for the appointment of a rapporteur to lead the settlement process or whether it is the responsibility of the bureau of the Commission to undertake the necessary follow-up.

With respect to the second category, under the 2010 Rules, the parties have an obligation to inform the Commission in writing, within 180 days of being notified of the decision, of all measures taken by the state party to implement the decision of the Commission. The Commission could request the state party concerned to supply further information on the measures taken in respect of the decision within 90 days of receiving the state’s response. If no response is received, the Commission could send the state a reminder to furnish the information within 90 days of the date of the reminder. However, Rules 112(5) to (9) of the 2010 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission mandated the rapporteur for a communication or any other commissioner specifically designated for that purpose to monitor the measures taken by a state party concerned to give domestic effect to the Commission’s recommendations on the communication.

The rapporteur had a discretion as to the national authorities to contact and the appropriate actions to take to discharge this monitoring responsibility, including making recommendations for further action by the Commission. The rapporteur was also required to present, at each ordinary session, the report during the public session on the implementation of the Commission’s recommendations. Furthermore, the 2010 Rules required the African Commission to draw the attention of the Sub-Committee of the Permanent Representatives Committee and the AU Executive Council to any situations of non-compliance with the Commission’s decisions and include information on any follow-up activities in its Activity Report. In practice, however, it remains unclear the extent to which commissioner rapporteurs responsible for cases have submitted or presented intersession activity reports on the state of implementation of the Commission’s decisions on the merits during the ordinary sessions of the African Commission since the adoption of the 2010 Rules. To be clear, intersession activity reports refer to the reports of commissioners on the various activities undertaken in respect of their country monitoring and special mandates after the last ordinary session of the African Commission. Such intersession activity reports are often considered during the public session of the Commission.

A cursory look at the intersession activity reports of commissioners between 2010 and 2020 shows mostly broad references to non-implementation of decisions by particular states in a number of reports. These references have often bordered on the general state neglect to implement recommendations in Concluding Observations and decisions on communications or letters of commendation given to a state for enacting legislation striking off one or few line items in the Commission’s recommendations.30 The intersession activity reports have contained very negligible information on the state of implementation of Commission decisions in particular cases. It may seem that this weak observance of Rule 112 by commissioner rapporteurs over the course of a decade contributed to the declining authority of the African Commission to follow up on cases requiring national authorities to take urgent implementation measures. More importantly, the low performance by commissioners in this regard may have also snowballed into the weak implementation of the 2020 Rules.

The 2020 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission substantially improve upon the provisions of the 2010 Rules with regard to the follow up of cases decided on the merit. Much like Rule 112 of the 2010 Rules, Rule 125 of the 2020 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission imposes a duty on the parties to inform the Commission in writing, within 180 days of the date of transmitting the decision to them, of all action taken by the state party to implement the Commission’s decision.31 Within 90 days of receiving the state’s written response, the Commission may request further information from a state concerned on the measures taken in response to its decision.32 If the Commission receives no response, it may send a reminder to the state party concerned to furnish an update within 90 days from the date of the reminder.33 The African Commission may also ask a national or specialised human rights institution with affiliate status to notify it of any measure it has taken to monitor or facilitate the implementation of the Commission’s decision.34

As in the case of the 2010 Rules, it is the commissioner rapporteur or any other designated commissioner who is responsible for monitoring the actions taken by the state party to give effect to the Commission’s decision under the 2020 Rules of Procedure.35 The rapporteur may contact such national authorities and take such action ‘as may be appropriate to fulfil his or her assignment, including recommendations for further action by the Commission as may be necessary’.36 They may also request or consider, at any stage of the follow-up proceedings, information from interested stakeholders regarding the extent of the state party’s compliance with the Commission’s decision. However, unlike the 2010 Rules, it is the bureau of the African Commission rather than the rapporteur for the communication that has a duty to report at the ordinary session on the implementation of its decisions.37 Rules 125(8) and (9) of the 2020 Rules allow the Commission to highlight in its Activity Report or refer matters of non-compliance with its decisions to the competent policy organs of the AU as provided in Rule 138 in order for ‘those organs to take the necessary measures for the implementation of its decisions’.38

Again, the absence of an institutionalised process of monitoring domestic implementation of decisions and recommendations under the 2020 Rules continues to be a fundamental setback for the African Commission. From March 2020 to date, no institutionalised system has been put in place to track state party compliance with previously-handed down and newer decisions and recommendations. In the wake of the novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19), the Commission’s activities and missions to the territories of state parties for 2020 and 2021 were severely hampered by the global COVID-19 lockdowns. Consequently, the switch to online activities meant that commissioners could not undertake promotion activities and missions through which to follow up on outstanding decisions and recommendations that have not yet been implemented by states. Only until 2022 did the Commission return to physical meetings and activities. Since then, the African Commission has been pre-occupied with a slouch of programmes and activities, enough to keep it distracted from the significant task of following up on domestic implementation.

Third, the lack of any institutionalised mechanism for tracking and following up on the extent of state parties’ domestic implementation has often left that part of the Commission’s monitoring role on autopilot. So far since 1986, the Commission has considered upwards of 133 state party reports. It has given its Concluding Observations on a majority of those reports, with a few still outstanding. Correspondingly, the Commission has received roughly 900 communications, approximately two-thirds of which have been determined. However, there is no indication of what decisions have and what decisions have not been implemented or the extent to which state parties have implemented any of the Commission’s historical findings.39 Despite having a rebranded website, the Commission is yet to have a stable and sustainable monitoring system in place – either at the Secretariat or online – to keep track of the status of domestic implementation. Lacking such a dedicated mechanism and having commissioners come and go periodically increase the danger of blotting out the Commission’s institutional memory on state implementation over time.

In the fairly recent past, the African Commission has organised three regional seminars on the implementation of its various decisions and recommendations for state parties and other stakeholders in Africa. The first seminar was convened in Dakar, Senegal from 12 to 15 August 2017 with a focus on the sub-regions of Central and West;40 the second seminar was convened in Zanzibar, Tanzania from 4 to 6 September 2018 with a focus on East and Southern Africa; and the third seminar was held in Pretoria, South Africa from 13 to 15 September 2023.41 The objective of the three regional seminars was specifically to assess the progress made in state party implementation of the Concluding Observations and other decisions issued by the African Commission. At the end of the seminars, stakeholders noted that some of the reasons for the poor implementation of the African Commission’s decisions were multi-dimensional and affected various stakeholders; that is, they bordered on challenges faced not only by the African Commission, but also by concerned states and the applicable NHRIs and CSOs engaged in human rights at the domestic level.42

2.2 Too many responsibilities exceeded by too few resources

The lack of an efficient follow-up mechanism is exacerbated not only by the enormity of the African Commission’s mandate but also by the meagre resources available to it. Currently, the human and material resources at the Commission’s disposal are distressingly disproportionate to the magnitude and continental scope of its broad mandate under the African Charter and other relevant instruments. Since its establishment in 1986, the African Commission has been bogged down by a growing number of setbacks. This includes the absence of a permanent headquarters; low budgetary allocation commensurate to its mandate; extreme understaffing; and a backlog of hundreds of pending cases.

In spite of the several limitations facing it, the African Commission is expected to discharge its promotion and protection mandate in respect of the 54 state parties to the African Charter, each with its own socio-political and economic challenges and complexities. While grappling with the continental scale of its responsibilities, the African Commission is continuously overawed by the task of convening its ordinary sessions at least four times a year. During the sessions, the Commission publicly engages states on the contents of their periodic reports, reviews the inter-session activities of commissioners and the respective special mechanisms they lead, and considers in private the complaints (cases) submitted to it. The retinue of back-to-back activities before, during and after the ordinary sessions and their impact on commissioners and the small professional staff at the Secretariat suggests that the African Commission often has barely any resources left to monitor the implementation of its decisions by state parties concerned.

2.3 Weak monitoring as the African Commission’s albatross

The African Commission’s credibility and guiding authority is at a crossroads. The pivotal role that the Commission plays in upholding and safeguarding human rights across the African continent all the more makes it important to proactively address the challenge of non-compliance by states from an institutional standpoint. To preserve its guiding authority, it is imperative that the Commission’s monitoring and guiding authority is maintained to effectively address the challenges it faces. One of the most pressing issues is the inadequate commitment displayed by certain state parties. Many state parties to the African Charter demonstrate a lack of political will in implementing the Commission’s decisions and recommendations, including provisional measures. This undermines the authority of the Commission and weakens its ability to ensure the protection of human rights.

Yet, addressing functional shortcomings is crucial for the Commission’s efficacy. For example, clarity in the types of remedies granted and the responsible institutions for monitoring implementation at the national level is necessary to ensure measurability in the implementation process, consistency and accountability. The Commission is yet to take full advantage of its rule-making powers under the African Charter to, at the very least, monitor the enforcement of its decisions at the national level, thereby fostering a stronger commitment to its recommendations and recommendatory authority. As Odinkalu notes:43

The Commission was not created to be a weak institution entirely at the mercy of forces outside its control and beyond its influence. Quite to the contrary, the Commission enjoys a wide but grossly under-utilised latitude for independent initiative, especially through its promotional and advisory mandates.

Also, non-compliance by state parties with their commitments under article 62 of the African Charter and the reporting obligations under the supplementary protocols erodes the effectiveness of the Commission’s oversight mechanism.44 It is disconcerting that some states prioritise the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) over their obligations under these critical provisions. This not only diminishes the importance of the Commission’s decisions but also hampers the progress towards a unified human and peoples’ rights framework in Africa. Another critical challenge to the Commission’s credibility is states’ perception that implementation of recommendations in the Concluding Observations and decisions on communications is voluntary due to its quasi-judicial nature. This perception must be rectified to reinforce the implicit bindingness of the Commission’s decisions, which draw from the binding obligations enshrined in the African Charter.45 In other words, while the African Commission’s decisions may be, rightly or wrongly, considered by states to be non-binding, the omnibus obligations to comply with the African Charter, establishing the same Commission, should be understood to imply that state parties have agreed in principle and in law to be bound by the Commission’s recommendations.46 Therefore, the quasi-judicial nature of the Commission and the sovereign authority of states should not be an excuse for non-implementation of recommendations that protect human rights and advance democratic accountability, as the recommendations are designed to strike a balance between domestic contexts and universal human rights norms.

Financial and institutional capacity constraints continue to impede the Commission’s efficiency. Inadequate financial resources and limited human resources hinder timely adoption, the publication of Concluding Observations, and handling of correspondences and communications. Sometimes delayed publication or non-publication of recommendations also obstructs the effective dissemination of the Commission’s decisions for appropriate action. Timely publication of decisions is crucial for the public to be aware of and demand accountability from their governments. To overcome these barriers, increased investment in the Commission’s human and material resources is essential to ensure its ability to effectively fulfil its mandate. Establishing sustained communication and engagement with state parties is equally necessary to foster cooperation and compliance. Unfortunately, the Commission’s relatively weak communication with states and the general public tends to hinder its visibility and impact. As such, a well-defined and integrated communication strategy that efficiently supports an institutionalised follow-up mechanism is vital to promote the Commission’s visibility within Africa and beyond.

3 The necessity for a new special mechanism for follow up

Addressing the challenges faced by the African Commission with respect to efficiently following up on the status of implementation of decisions and recommendations requires a robust institutional approach. Currently, the Commission has 16 special mechanisms, comprising 12 single and group thematic mechanisms and four internal mechanisms (see Figure 1 below for the current list of special mechanisms).47 While the Commission has made notable strides in various thematic areas through the work of its special mechanisms, none of these specifically deals with the issue of follow up. Even the Working Group on Specific Issues, which should ideally have been tasked with the important role of following up on implementation, has largely had a nebulous mandate, low public engagement and unclear impact. Even although the African Charter does not specifically list ‘follow-up’ as a direct responsibility of the Commission, the Commission must not resign to the fate, poignantly described by Odinkalu, that it is ‘a juridical misfit with a treaty basis that is dangerously inadequate and an institutional mechanism liable, ironically, to be slated as errant when it pushes the envelope of interpretation positively’.48

The essence of an institutionalised system of conducting follow ups and monitoring is bolstered by the existence of such implementation monitoring mechanisms at the level of the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (African Children’s Committee) and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Court). In the case of the African Children’s Committee (which has a strikingly similar mandate to that of the Commission) the lack of an express provision for following up on implementation of its decisions and recommendations to state parties to the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (African Children’s Charter) has not prevented the Committee from establishing a mechanism for monitoring domestic implementation.

On 8 September 2020 the African Children’s Committee established the Working Group on Implementation of Decisions (WGID), with no comparable mechanism at the African Commission since its establishment.49 The WGID was established pursuant to article 38(1) of the African Children’s Charter and Rule 58 of the Revised Rules of Procedure of the African Children’s Committee to monitor progress in implementing its decisions and recommendations. The goal is to ensure state parties fully implement all decisions and recommendations through ongoing review and targeted activities. In the Resolution establishing the WGID, the Committee noted that the need ‘to regularly assess [sic] whether the actions taken by states constitute a satisfactory remedial response’ and ‘the fact that regular and continued monitoring of states’ compliance with the decisions and recommendations of ACERWC is key to the full realisation of children’s rights’ were important considerations for deciding to establish a special mechanism on implementation of decisions.50 In 2022 the African Children’s Committee adopted an amendment to the 2020 Resolution in order to expand the scope of decisions to be monitored by the WGID to include decisions by other AU policy organs and institutions relating to children in Africa.51

One of the very first activities to be undertaken by the WGID is the draft study on the status of implementation of decisions and recommendations of the African Children’s Committee.52 The primary objective of the study is to evaluate the implementation status of the Committee’s decisions and recommendations. Although yet to be adopted, the study’s methodology involved a comprehensive review of the Committee’s decisions and data collection conducted by the consultant. To enrich the study with practical insights, questionnaires were distributed to all member states, NHRIs and CSOs. The study received responses from only nine state parties, seven NHRIs and three CSOs.53 The study presents major findings, recommendations and conclusions, offering an overview of the present status of the implementation of decisions on communications and assessing the challenges faced by state parties in executing the Committee’s decisions. The draft also examines the role of the Committee in encouraging state parties to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of NHRIs. The recommendations specifically emphasise the significant role NHRIs could play in implementing and monitoring the follow-up of its decisions and recommendations.54

To deepen the effectiveness of the WGID, the African Children’s Committee at its 43rd ordinary session held from 15 to 25 April 2024 decided to expand the WGID’s membership to include four external experts in the field knowledgeable on the subject matter of state party compliance and domestic implementation. The expansion is intended to drive its activities and programmes on monitoring implementation.55 Those selected as experts will be appointed immediately after the 13 June 2024 deadline and their responsibilities will include supporting the WGID in disseminating the Committee’s findings and recommendations; providing expertise and drafting documents, standards, guidelines, and policy briefs; offering technical assistance to the Committee; and regularly gathering information from civil society actors and NHRIs on the implementation of the Committee’s decisions and recommendations.56 On 1 April 2022 the Committee adopted Resolution 16/2022 on implementation of decisions and recommendations of the African Children’s Committee by calling upon states, NHRIs and CSOs to establish and coordinate domestic mechanisms for the implementation of its decisions and recommendations.57

From 23 to 24 February 2023 the African Children’s Committee’s convened a continental workshop on implementation of its decisions and recommendations in Nairobi, Kenya, led by the WGID.58 The workshop aimed to achieve several critical objectives, including raising awareness about the Committee’s findings and recommendations; outlining the structures and roles of NHRIs in child rights protection; sharing best practices from NHRIs and CSOs on implementing the Committee’s decisions and recommendations at the local level. Additionally, the workshop sought to identify key areas for future recommendations to ensure effective and continuous collaboration between NHRIs, CSOs and the Committee in implementing the latter’s decisions, as well as to explore ways in which NHRIs and CSOs can better engage at both national and regional levels to support the implementation of the African Children’s Charter. This may be contrasted with the African Commission’s inability to convene stock-taking workshops on implementation without external support or to do so on a regular and sustainable basis. Also, at the Working Group and subsequently during its 41st ordinary session, the Committee constructively engaged with NHRIs59 and key AU organs and institutions such as the Economic, Social and Cultural Council and the African Peer Review Mechanism on bootstrapping their relationship through better inter-institution coordination for more effective monitoring of domestic implementation of the African Children’s Charter.60

More so, as part of its interest in systematically tracking implementation of children’s rights and welfare in Africa, the African Children’s Committee undertook a rigorous study to evaluate the extent of state party implementation of its Agenda 2040 focusing on fostering an Africa fit for children, adopted in 2015, during its commemoration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the African Children’s Charter. This aspirational policy document seeks to achieve ten key goals for the advancement of children’s rights and welfare in Africa by 2040. After five years of its launch, the African Children’s Committee considered it timely to evaluate the extent of implementation of the 2020 Agenda particularly as it relates to state parties’ implementation of recommendations contained in decisions on communications submitted to the Committee; reports on investigative missions of the Committee; national reports on implementation of child rights; and reports on various initiatives within the AU related to children’s rights.’ In March 2021, at the occasion of the celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of the African Children’s Charter, the Committee published an evaluation study to determine the status of the implementation of the Agenda.61

However, the WGID is still at its infancy stage, having been established only recently during the COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020. As such, not much of its work on tracking implementation has yet been published to convince of its effectiveness or otherwise. Much of what it has done has been to lay the ground work for demonstrably and effectively monitoring domestic implementation. So far, a preliminary assessment of state parties’ implementation under the draft study suggests that challenges still persist. This is confirmed in the recent work of Kangaude and Murungi evaluating the status of implementation of the African Children’s Charter in 10 African countries, where they concluded that while ratification of the Children’s Charter has ‘brought notable impacts in various countries’ with regard to the rights and welfare of children, there remain ‘immerging challenges’.62 In comparison to the African Commission which is yet to conduct such a detailed study, the draft study currently being considered by the African Children’s Committee will enable the latter to have its finger on the pulse of implementation down to the beat. It will potentially have disaggregated data on domestic implementation from its inception. This information will no doubt enable the Committee to better taylor its engagement with non-complying or non-implementing state parties to the African Children’s Charter.

In the case of the African Court, under the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Court Protocol), state parties agree to comply with the decisions of the Court in any case in which they are parties.63 Unlike the African Charter, the African Court Protocol makes express provision for monitoring state party compliance with the Court’s decisions by reposing that responsibility on the Council of Ministers of the AU.64 To support this monitoring process, the African Court must also submit its annual activity report to the AU Assembly, which report ‘shall specify, in particular, the cases in which a state party has not complied with the Court’s judgment’.65 This is with a view to allowing the Assembly to consider the report and engage the state party concerned. Much unlike the African Commission and the African Children’s Committee, the African Court does not undertake monitoring of domestic implementation through a working group or standing committee.

This suggests that the institutional responsibility for following up and monitoring domestic compliance with the decisions of the African Court is that of the Council of Ministers and the Assembly, complemented by the human rights-monitoring role of the African Commission under the African Charter. As a judicial body, once the Court has issued a decision, it becomes functus officio (which means that it lacks the power to re-examine its decision). It is not the Court’s responsibility to subsequently undertake promotional activities to convince state parties to comply with its decision. That responsibility lies with the Council of Ministers and the Assembly and, in the past, has been supported by the Commission when on promotion missions to the territory of a state party concerned. Although the Court conducts ‘outreach’ and ‘sensitisation missions’ to raise awareness about the African Court Protocol, such extra-judicial activities do not constitute follow-up or monitoring roles.66 Indeed, it would be highly improper for the Court to hand down a decision and subsequently seek to ‘follow up’ on its implementation during its outreach or sensitisation missions.

In practice, however, the African Court relies on the provisions of its 2020 Rules to monitor compliance with its decisions. Under Rule 81 of the Rules of Court, state parties concerned in a case decided by the Court are by order of court obliged to submit reports on compliance with the decisions of the Court which will be transmitted to the applicant(s) for observations.67 The Court may obtain relevant information on state parties’ implementation from other reliable sources in order to assess compliance with its decisions. If there is a dispute as to whether or not a state party has complied with the decision of the Court, the Court can convene a hearing to assess the status of implementation and make a finding including issuing a compliance order.68 Where a state party fails to comply with its decision, the Court must report the non-compliance to the Assembly and forward all relevant information for the purpose of execution.69

The Court accurately keeps track of non-implementation of its decisions by state parties to the African Court Protocol by annexing to its annual activity reports to the AU policy organs a list of decisions with which state parties have not yet complied.70 It does this with the expectation that such policy organs will exert their power under the AU Constitutive Act and the respective Rules of Procedure of the AU Executive Council and the AU Assembly to make binding decisions on states, non-compliance of which could attract sanctions.71 As part of its diplomatic engagement with states, the African Court undertakes courtesy visits (which are similar to missions undertaken by the African Commission and the African Children’s Committee) and uses such visits as an auspicious occasion to encourage non-state parties to ratify the African Court Protocol.72 It could hold regular judicial dialogues to encourage domestic courts, litigation attorneys and human right-focused organisations to incorporate its jurisprudence in domestic cases.73 In contrast, while the African Commission does cover the issue of non-implementation of its decisions and recommendations in its activity reports, it does not do so with the same venir, detail and comprehensiveness as the African Court. This lack of detail in the Commission’s reports suggests that it does not yet have up-to-date records, figures and statistics of implementation and non-implementation of its decisions by state parties.

Argubaly, the existence of dedicated mechanisms for ensuring follow ups and monitoring implementation notwithstanding, there is still an increasing spate of non-compliance with the decisions of the African Children’s Committee and the African Court.74 While the presence of dedicated mechanisms for monitoring implementation at the African Children’s Committee and the African Court has not resulted in greater implementation of itself, it is achieving the underlying need for both bodies to have their fingers on the information pulse on implementation. This is because the issue of compliance is external and hardly in the control of both these institutions. Yet, with these bespoke institutional processes established to help them properly engage states on their implementation and compliance obligations, these institutions are better able to follow up and monitor domestic implementation. For instance, at the Court, a dashboard and documentary matrix have been created to help the Court track cases and provide the public with up-to-date information on decisions handed down by the Court. At the African Children’s Committee, the relatively recent creation of the WGID and the draft study on implementation will help the Committee better engage states to ‘[e]stablish a comprehensive national reporting and monitoring mechanism for the implementation and compliance with the Committee’s decisions and recommendations as well as reporting on the status of implementation of decision to the Committee’.75

With respect to the African Commission, its activity reports year in, year out reveal that the rate of compliance by state parties with its decisions, requests for provisional measures, and letters of urgent appeal ‘remains low’.76 Yet, there is no information, dashboard or matrix of data showing which decisions have been implemented and which have not. At the moment, the only reliable source of any sketchy data on non-implementation by state parties is the activity reports.77 I argue that, if anything, the seemingly increasing number of cases of unimplemented decisions recounted by the Commission in its activity reports has reached a critical point, necessitating the creation of a dedicated special mechanism to follow up on domestic implementation, as can be seen at the African Children’s Committee. A special mechanism of the Commission is any mechanism established pursuant to Rule 25 of the 2020 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission. The provision of Rule 25 allows the African Commission to create subsidiary mechanisms such as Special Rapporteurs, committees and working groups.78 While not a controversial recommendation, the Rules of Procedure of the African Commission anticipate potential divergences of opinions among members of the Commission on such matters. As such, should the creation and membership composition of such a follow-up special mechanism become debatable or divisive, the Rules make provision for the matter to be decided by voting if consensus cannot be achieved.79 Under the Rules, the African Commission is required to determine the mandate and terms of reference of such a mechanism at the time of its creation. From an institutional perspective, the proposal for a special mechanism responsible for follow-up should encompass several key elements to ensure its effectiveness, sustainability and transparency.

In the next few paragraphs I list the institutional benefits of having a systematic approach to tracking and monitoring state party compliance with the African Commission’s decisions and recommendations.

|

Special mechanisms |

Year created |

|---|---|

|

Committee on the Protection of the Rights of People Living with HIV (PLHIV) and Those at Risk, Vulnerable to and Affected by HIV |

2010 |

|

Working Group on Extractive Industries, Environment and Human Rights Violations |

2009 |

|

Working Group on the Rights of Older Persons and People with Disabilities in Africa |

2007 |

|

Working Group on Death Penalty, Extra-Judicial, Summary or Arbitrary Killings and Enforced Disappearances in Africa |

2005 |

|

Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders and Focal Point on Reprisals in Africa |

2004 |

|

Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information |

2004 |

|

Special Rapporteur on Refugees, Asylum Seekers, Internally Displaced Persons and Migrant in Africa |

2004 |

|

Committee for the Prevention of Torture in Africa |

2004 |

|

Working Group on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights |

2004 |

|

Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities and Minorities in Africa |

2000 |

|

Special Rapporteur on Rights of Women |

1999 |

|

Special Rapporteur on Prisons, Conditions of Detention and Policing in Africa |

1996 |

|

Internal mechanisms |

Year created |

|

Committee on Resolutions |

2016 |

|

Working Group on Communications |

2011 |

|

Advisory Committee on Budgetary and Staff Matters |

2009 |

|

Working Group on Specific Issues Related to the work of the African Commission |

2004 |

Figure 1: List of Subsidiary Mechanisms established by the African Commission

First, while national level mechanisms are important for the domestic implementation of Commission decisions, it is equally crucial that ‘implementation is carried out in combination with an effective regional follow up system’.80 As such, the African Commission should clearly stipulate the mandate, composition and terms of reference of a special mechanism dedicated almost entirely to follow up. This includes specifying the types of decisions and recommendations it will monitor (for example, Concluding Observations, decisions on communications and, possibly, resolutions); its membership composition, which may include the states it will cover; and the human rights issues on which it will focus. A well-defined mandate ensures that the mechanism’s efforts are targeted and coherent. The special mechanism should also be empowered to develop internal follow-up processes that guarantee that its work is methodical and measurable. In the next part of this article I will make an effort to articulate the role of the special mechanism in addressing, in a practical way, the challenges faced by the African Commission in effectively monitoring the implementation of its findings.

Second, the African Commission needs to formalise the establishment and functioning of the special mechanism responsible for follow-ups within its Rules of Procedure. This formalisation will ensure that the follow-up process becomes an integral part of the Commission’s institutional framework, making it less susceptible to changes and loss of institutional memory with periodic shifts in leadership. Ideally, this may require that the current ad hoc arrangement of having a commissioner rapporteur for a communication should be replaced with a standing Committee or Working Group on Follow-up on Implementation of the Decisions of the African Commission. The membership composition, as proposed in the earlier point, may be inclusive of various stakeholders – representatives of national authorities, NHRIs, CSOs and human rights experts. The African Commission can set this in motion by converting the current Working Group on Specific Issues to a Working Group on (Follow-up on) Impementation of Decisions through a resolution to that effect. To achieve practical results, membership may be designed in either of two ways: one, being inclusive of a particular group of states for which the Commission seeks to prioritise implementation; two, allowing the state parties that are the focus of implementation at any given time to participate in the proceedings in order to foster a cordial and constructive engagement with the Commission in the process. The resolution establishing or reconstituting the working group can authorise this process in clearer details.

Third, the creation of a special mechanism would require that adequate human and financial resources are allocated for the smooth functioning of the Commission’s follow-up activities. This may include appointing dedicated staff with expertise in human and peoples’ rights monitoring, data collection and analysis. Adequate funding within the existing framework of programme allocations should be allocated to support the mechanism’s activities, such as travel for on-site visits, research or engagement with national authorities, NHRIs, civil society and other stakeholders, who can play a crucial role in providing information and monitoring implementation on the ground.81 The special mechanism will essentially maintain formal channels of communication and collaboration with these stakeholders to monitor domestic implementation of the African Commission’s decisions.

Fourth, the African Commission also needs to develop comprehensive operational guidelines that outline the step-by-step procedures and methodologies for conducting follow-up activities. These guidelines should specify how and when the mechanism will engage with state parties, what information it will seek, and how it will report findings.

Last, and perhaps the most pressing need for a dedicated special mechanism on follow-ups, is the need to prepare and submit regular reports to the Commission, summarising its findings, activities and recommendations. The continuity of its programmes and the regularity of reporting by the special mechanism will not only institutionalise the follow-up process, but also preserve the institutional memory of the Commission with respect to its implemented and non-implemented decisions. Ideally, the reports of the mechanism should be made available to the public to ensure transparency and accountability.

By adopting a comprehensive institutional approach based on the above justifications, the African Commission can establish a special mechanism for follow-up that is well-equipped to address the challenges in monitoring domestic implementation of decisions and recommendations, promote human rights, and hold state parties accountable for their obligations under the African Charter and other relevant regional and international human rights instruments.

4 Structure and role of the special mechanism

The establishment of a special mechanism on follow-up under Rule 25 of the 2020 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission should come with clearly-defined functions and responsibilities. By default, it is expected that the special mechanism will closely monitor the implementation of decisions and recommendations made by the African Commission in cases involving state parties. This includes tracking timelines and assessing the progress of implementation. Also, the special mechanism should engage with state parties to facilitate compliance with Commission decisions and recommendations. This may involve consultations, diplomatic negotiations, providing technical support and assistance, and clarification of obligations under the African Charter. Through the support of the Secretariat, the special mechanism should maintain detailed records of the implementation process, including correspondence, meetings, and any challenges faced. These records should be made available to the Commission and the public, in order to ensure transparency and accountability.

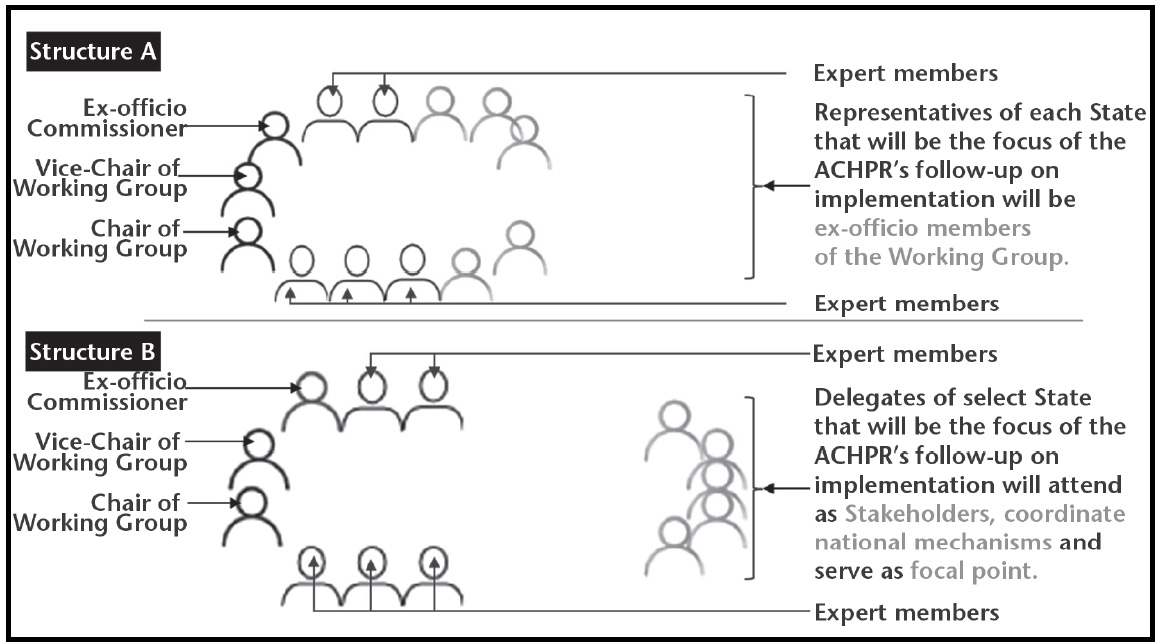

In Figure 2 below, I propose a relatively novel structure for the special mechanism to be created. It should be in the form of a Working Group on the Follow-up and Implementation of Decisions and Recommendations as against a single mandate holder, much like the WGID of the African Children’s Committee. The working group will function in accordance with the Standard Operating Procedures of Special Mechanisms of the African Commission (SOPs). It will have a composition structure of either of two options (Structure A or Structure B) as in Figure 2, which is consistent with the Commission’s SOPs. That is, it will be composed of three commissioners and five expert members.

Under Structure A, the working group will have a Chairperson, Vice-Chairperson, an ex officio commissioner and five expert members experienced in implementation of and compliance with the decisions of human rights bodies as well as feature state representatives as ex officio members. The purpose of this structure would be to engage volunteer states intentionally and diplomatically in meetings where domestic implementation and compliance actions can be determined, measured and tracked. The volunteer states will then be replaced by another set of volunteer states after substantial implementation or compliance, in the opinion of the Commission, has been achieved and documented.

Figure 2: Proposed composition of the Working group on follow-ups and implementation of decisions and recommendations

On the other hand, under Structure B, which may be the preferred structure, the working group will have three commissioners (Chairperson, Vice-Chairperson and ex officio commissioner) and five expert members experienced in implementation of and compliance with decisions of the human rights bodies. At the same time, the working group will invite to its meetings state delegates of no more than five representing a number of states prioritised by the Commission for monitoring implementation over a specific period of time. By participating in the sessions, the delegates will serve as focal points and be responsible for engaging and coordinating the activities of relevant national authorities to ensure that each aspect of the Commission’s decisions and recommendations is implemented and providing timely and accurate feedback.

Regardless of which structure is adopted, the special mechanism will enable the Commission to more effectively engage state parties on their human and peoples’ rights obligations under the African Charter. If challenges or obstacles arise during the implementation process, the special mechanism or the bureau of the African Commission will be able to work with national authorities (and mobilise the support of NHRIs and accredited CSOs on the ground) to resolve these. This should be done through dialogue and diplomacy and, in the process, promote cooperation between the state party and the African Commission in accordance with article 45(1)(c) of the African Charter.82 Furthermore, as part of promoting cooperation, the mechanism should support capacity-building efforts within state parties to enhance their ability to fulfil their obligations under the African Charter. This can include training programmes, sharing best practices and having special dialogue sessions with national authorities.

To be effective in the follow up of domestic implementation, the special mechanism must promptly get to work soon after decisions and recommendations are made by the African Commission and in line with the Commission’s Rules of Procedure. This timely intervention will serve to prevent prolonged non-compliance and promote the prompt realisation of human rights within state parties. In so doing, the special mechanism should diplomatically engage state parties in respect of which decisions and recommendations have been made in order to foster a constructive and cooperative relationship. This approach is more likely to yield positive results compared to confrontational tactics.83 The special mechanism should also readily offer technical assistance and clarification of obligations in order to demonstrate its commitment to helping state parties meet their obligations under the African Charter. This will reduce misunderstandings, promote a sense of partnership and contribute to its effective engagement with state parties. In all of this, it is pertinent to emphasise the need to provide training support to the Secretariat’s staff and relevant stakeholders, including state officials, CSOs and human rights defenders, to enhance their understanding of the implementation process and the necessity for effective monitoring.

With respect to improving reporting on the African Commission’s mandate to monitor state party implementation of its decisions and recommendations, the special mechanism’s detailed documentation and reporting will increase transparency with respect to the implementation process. This transparency will operate to enhance the Commission’s credibility and enable the public to hold both the Commission and state parties accountable. In this regard, the special mechanism may establish feedback channels through which state parties can provide updates on their progress in implementing recommendations. This two-way communication will ensure that the African Commission’s monitoring efforts remain dynamic and responsive. Moreover, periodic evaluations of the special mechanism’s effectiveness should be conducted, as has been done recently with the existing special mechanisms at the Commission’s Secretariat. These evaluations should assess its impact on state party compliance. This will allow the Commission to gauge the effectiveness of its decisions and recommendations.

The records and insights of the special mechanism may also be used to refine the African Commission’s strategies and approaches to implementation. This adaptive approach will ensure that the Commission’s efforts become increasingly effective over time. Not only that, granting access to records and reports maintained by the special mechanism has the potential to empower CSOs and human rights defenders to raise awareness and advocate the implementation of Commission findings and recommendations. This, I believe, will strengthen the overall impact of the Commission’s work. Furthermore, the African Commission may also explore opportunities for peer review with and learning from other regional and international human rights bodies with successful follow-up mechanisms and approaches. This exchange of best practices can inform the development and improvement of the Commission’s follow-up mechanism.

5 Conclusion

Based on the foregoing, it is clear that the African Commission cannot continue to rely on the current ad hoc arrangement for monitoring implementation, if its decisions and recommendations are to achieve the impact for which they are intended – that is, of promoting and protecting human and peoples’ rights domestically. For there to be a positive shift from the current state of weak implementation, it must do something differently, drastically and urgently. The mounting challenges of state parties’ non-implementation of and non-compliance with the African Charter have reached an inflection point that demand impact-driven approaches for significant results. There is a pressing need for a special mechanism to address the growing issue of non-compliance with the Commission’s decisions and recommendations. This analysis provides ample justifications for why the African Commission should set up a dedicated special mechanism responsible for the follow-up of domestic implementation.

A special mechanism will play a crucial role in ensuring compliance with the provisions of the African Charter and ultimately enhancing the African Commission’s effectiveness in advancing human rights in Africa. This will come about by the mechanism’s ability to systematically monitor the implementation measures adopted by national authorities, diplomatically engage with state parties, document progress, and report on its activities to the Commission and the wider public during the ordinary sessions of the Commission. Going by the achievements of existing special mechanisms at the Commission, there is an added advantage of adopting an institutionalised approach to the follow-up of state implementation. This includes applying a uniformly-coordinated operational methodology for routinely engaging states and having organised reporting obligations through the inter-session activity reporting process. These will constantly keep the Commission up to date on the state of implementation as well as put the Commission on its toes with regard to its performance on this aspect of its mandate.

Establishing a special mechanism for follow-ups is also essential for upholding the credibility and impact of the African Commission. The challenges facing the Commission demand a multifaceted institutional response to ensure that its credibility and guiding authority are upheld. To enhance its monitoring function, the Commission may consider revising the provisions of Rules 93, 110, 112 and 125 in its 2020 Rules of Procedure for the implementation of recommendations to bring this objective of a special mechanism for follow up to fruition. It is only by addressing the inadequate commitment of states, its communication deficits and functional shortcomings with regard to follow-ups that the Commission can strengthen its role as a guardian of human and peoples’ rights in Africa. This will contribute to a more just and rights-respecting continent, where human and peoples’ rights are protected for all.

-

1 African Charter art 45; R Murray & D Long ‘Monitoring the implementation of its own decisions: What role for the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights?’ (2021) 21 African Human Rights Law Journal 837-838; F Viljoen International human rights law in Africa (2012) 340-341; H Onoria ‘The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the exhaustion of local remedies under the African Charter’ (2003) 3 African Human Rights Law Journal 1-2.

-

2 R Murray & D Long The implementation of the findings of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (2015) 3, 33, 44, 64, 210 & 242.

-

3 GJ Naldi ‘Future trends in human rights in Africa: The increased role of the OAU?’ in M Evans & R Murray (eds) The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights: The system of practice, 1986-2000 (2002) 1, 3.

-

4 African Charter art 45(1)(a).

-

5 African Charter art 62; Rule 78 of the Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020.

-

6 R Murray and others ‘Monitoring implementation of the decisions and judgments of the African Commission and Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ (2017) 1 African Human Rights Yearbook 150, 158.

-

7 Murray and others (n 6) 150.

-

8 Murray & Long (n 2) 30.

-

9 VO Ayeni & A von Staden ‘Monitoring second-order compliance in the African human rights system’ (2022) 6 African Human Rights Yearbook 3, 5; GM Wachira & A Ayinla ‘Twenty years of elusive enforcement of the recommendations of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights: A possible remedy’ (2006) 6 African Human Rights Law Journal 468.

-

10 F Viljoen & L Louw ‘State compliance with the recommendations of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights between 1993 and 2004’ (2007) 101 American Journal of International Law 33; Wachira & Ayinla (n 9) 466, who argue that ‘[a] human rights guarantee is only as effective as its system of supervision’.

-

11 Rules of the Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 83(2).

-

12 Murray & Long (n 1) 843.

-

13 R Murray & E Mottershaw ‘Mechanisms for the implementation of decisions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ (2014) 36 Human Rights Quarterly 349, 352.

-

14 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 25(3).

-

15 CA Odinkalu & C Christensen ‘The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights: The development of its non-state communication procedures’ (1998) 20 Human Rights Quarterly 235, 279.

-

16 African Charter art 45(1)(a).

-

17 Naldi (n 3) 6.

-

18 As above.

-

19 As above. See Grand Bay Declaration para 15; Kigali Declaration para 27.

-

20 Viljoen (n 1) 341.

-

21 African Charter art 42(2).

-

22 Murray & Long (n 1) 842.

-

23 The first Rules of Procedure of the African Commission was adopted on 13 February 1988 during its 2nd ordinary session in Dakar, Senegal, held from 2-13 February 1988. Also see UO Umozurike ‘The procedures of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights for the protection and promotion of human rights’ (1992), https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1155972/the-procedures-of-the-african-commission-on-human-and-peoples-rights-for-the-protection-and-promotion-of-human-rights/ (accessed 21 July 2023).

-

24 The second Rules of Procedure of the African Commission were adopted on 6 October 1995 during its 18th ordinary session in Praia, Cabo-Verde, held from 2 to 11 October 1995.

-

25 27th extraordinary session held in Banjul, The Gambia from 19 February to 4 March 2020.

-

26 Concluding Observations refer to the findings and recommendations by a treaty-monitoring body on the reports of state parties submitted under a particular human rights treaty. In the context of the African Commission, Concluding Observations are the observations made on state party reports submitted pursuant to art 62 of the African Charter and relevant provisions of the supplementary protocols. They contain general and specific recommendations for state parties to comply with their obligations under the African Charter and other relevant regional and international human rights instruments. Conversely, communications resolved by amicable settlement or determined on the merits are cases that have been submitted before the Commission for a determination as to whether or not there has been a violation of the rights and freedoms enshrined in the African Charter and any other relevant African human rights instrument.

-

27 The 2020 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission were adopted during the 27th extra-ordinary session held in Banjul, The Gambia, from 19 February to 4 March 2020.

-

28 Under the Rules of Procedure, a commissioner rapporteur is designated to be in charge of a communication submitted before the Commission. See Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2010 Rules 88(2), 90(4)(a) & 97(1); and Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rules 93(1), 112(3)(a) & 110(2).

-

29 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission Rule 123(7).

-

30 Under Rule 7(e) of the 2020 Rules of Procedure of the Commission, commissioners have a responsibility to facilitate ‘the implementation of a provision of the Charter or its Protocols’.

-

31 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 125(1).

-

32 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 125(3).

-

33 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 125(4).

-

34 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 125(2). Cf Rule 70(3) of the 2020 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020.

-

35 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 114(6); Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 125(5).

-

36 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 125(6).

-

37 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 125(7).

-

38 Rules of Procedure of the African Commission 2020 Rule 138.

-

39 Murray & Long (n 1) 842.

-

40 African Commission ‘Report of the Regional Seminar on the Implementation of Decisions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights 12-15 August 2017, Dakar, Senegal’ 29 August 2018, https://achpr.au.int/en/news/statements/2018-08-29/report-regional-seminar-implementation-decisions-african (accessed 4 July 2023).

-

41 African Commission ‘Press Release: Regional Seminar on Implementation of the Decisions of the Commission’ 5 August 2018, https://achpr.au.int/en/news/press-releases/2018-08-05/press-release-regional-seminar-implementation-decisions-commis (accessed 4 July 2023); Centre for Human Rights (University of Pretoria) ‘Centre for Human Rights holds a conference on implementation and domestic impact of the decisions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ 22 September 2023, https://t.ly/vp5Ix (accessed 31 October 2023).

-

42 Murray & Mottershaw (n 13) 360-361.

-

43 CA Odinkalu ‘Implementing economic, social and cultural rights under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ in Evans & Murray (n 3) 176, 216.

-

44 M Evans, T Ige & R Murray ‘The reporting mechanism of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ in Evans & Murray (n 3) 36, 37.

-