Tracy SN Muwanga

LLB LLM LLD (Pretoria)

Postdoctoral fellow, Department of Private Law and Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

https://orcid.org/000-0002-0359-5252

Lise Korsten

BSc BSc (Hons) (Stellenbosch) MSc PhD (Pretoria)

Professor, Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0232-7659

Edition: AHRLJ Volume 24 No 2 2024

Pages: 632 - 658

Citation: TSN Muwanga & L Korsten ‘The right to food in South Africa: A consumer protection perspective’ (2024) 24 African Human Rights Law Journal 632-658

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2024/v24n2a10

Download article in PDF

Summary

The right to food is a recognised human right, particularly within socio-economic rights. In South Africa, this right is still evolving but has become increasingly significant as global hunger worsens. Importantly, the right to food means not the right to be given food, but the right to access safe, nutritious and affordable food, which is crucial for health and development. Malnutrition, especially in low and middle-income countries, affects both children and adults. It includes various forms of undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies that impair the body’s ability to grow and function properly. There are also challenges related to obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases, which have become major public health concerns. NCDs such as heart disease and cancer often stem from poor diets and lifestyle choices. In South Africa, unhealthy eating habits – such as the consumption of foods high in sugar, salt and unhealthy fats – have contributed to the rise in these conditions, especially in lower-income communities where healthier food is less accessible for different vulnerable groups. South Africa’s health system is burdened by a combination of communicable and non-communicable diseases, making the need for preventative measures more urgent. Regulatory interventions are crucial to managing this health crisis. This article emphasises the need for stronger legislation, particularly around food labelling and advertising, to protect consumers. The article analyses the right to food and food insecurity from a national and global perspective, as well as conducting a review of case law surrounding food rights. The article will further discuss South Africa’s food law and regulatory interventions to combat NCDs, focusing on consumer protection through labelling and advertising regulations, particularly the proposed new regulations, which are yet to be passed, on labelling and advertising of foodstuffs.

Key words: non-communicable diseases; human rights; consumer protection; food security; food law; right to food; labelling requirements

1 Introduction

The right to food is considered a human right, falling under socio-economic rights.1 While still a fairly recent concept in terms of its content, particularly in South Africa, the importance of this right has been progressively increasing over time as world hunger continues to worsen. As will be discussed in greater detail below, the right to food does not imply the right to be given food. Instead, it bestows on everyone a right to have access to food that is safe, accessible, affordable, as well as nutritious. Nutrition is an integral part of an individual’s health and development. Malnutrition has resulted in approximately 45 per cent of deaths among children under the age of five, mostly occurring in low and middle-income countries.2 Malnutrition takes on various forms, including undernutrition, which has four broad sub-forms, namely, ‘wasting, stunting, underweight, and deficiencies in vitamins and minerals’;3 and micronutrient-related malnutrition. The latter refers to inadequacies in mineral and vitamin intake which enable the body to produce hormones, enzymes and other substances essential for proper growth and development.4

Micronutrient-related malnutrition has two further sub-categories, namely, overweight and obesity as one sub-category; and diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as the second. Obesity poses a global public health problem.5 South Africa is one of the countries in the world with the highest prevalence of obesity, with projections estimated to be 47,7 per cent in females and 23,3 per cent in males by the year 2025.6 The high prevalence of obesity further leads to an increase in NCDs, to which this article will mostly refer.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), NCDs account for 71 per cent of all global deaths.7 In 2017 the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that 22 per cent of all deaths were diet-related.8 This makes NCDs the leading cause of deaths worldwide. NCDs are referred to as chronic illnesses, for instance cancer, resulting from a combination of physiological, genetic, behavioural and environmental factors.9 These types of illnesses are mainly chronic respiratory diseases, such as asthma, and cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks or strokes.10

South Africa has a poor health prognosis and has been associated with ‘a quadruple burden of communicable diseases, NCDs, maternal and child health, as well as injury-related disorders’.11 There is a further growing trend of multi-morbidity, with the increasing need for resources to be allocated to the management and treatment of ‘human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/NCDs and tuberculosis mycobacterium (TB)/diabetes’.12 A shift in dietary patterns has also led to an increase in NCDs, with the poorer communities moving away from the more traditional healthier foods, and adopting diets that are high in sugar, salt and trans fats, leading to food-related NCDs.13 The reason behind this shift in patterns has been determined to be the socio-economic development in the country, as well as globalisation that has resulted in a change in the food environment, with sweet and salty snacks, sugar-sweetened beverages and fast foods being made more affordable and easier to access.14

The situation involving food-related NCDs in South Africa thus is in need of regulatory interventions to help curb the increasing number of NCDs in South Africa, for instance, the passing of the Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs’,15 which will be discussed below. Consumers can be highly influenced by promotional marketing within the food industry, with suppliers generally being large enterprises whose sole purpose is to make a profit, even at the expense of the health of consumers.16 In addition to this, vulnerable groups, that is, low-income persons, children and individuals who are illiterate or have trouble reading and understanding food labels and advertisements, are at a greater risk of making detrimental food choices that could affect their health negatively.17 The government has proposed measures in the past, such as a sugar tax on sweetened drinks and limits on salt in common food. However, Reddy believes that these steps are not enough to protect consumers from NCDs, and broader legislation is needed.18

This article investigates the legislation surrounding consumer protection in relation to NCDs, with particular focus being placed on labelling requirements and adherence. The article will first provide a brief discussion on food security and food law internationally and nationally, as well as legislation and case law linked thereto, as a means to unpack the right to food.

2 Global food insecurity

Food insecurity is defined by the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) to exist when a person lacks ‘regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life’.19 The reasons for this may vary from the unavailability of food, to a lack of the resources necessary to obtain nutritious food.20 In 2015 the African Union (AU) Commission adopted the Agenda 2063, a framework aimed at fostering sustainable development across Africa including, but not limited to, improvements in health and nutrition.21 On a more global scale, in the same year the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) issued the Resolution on the 2030 agenda for sustainable development.22 This Resolution demonstrates the ambition and scale of the new universal agenda through 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets.23 These goals range from achieving gender equality and clean water and sanitation, to ending poverty. For purposes of this article, goal 2 is relevant as it seeks to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.24 Accordingly, these goals should be reached by the year 2030.

Achieving goal 2 has had major setbacks, recently more due to the COVID-19 pandemic (pandemic). The pandemic brought with it growing numbers of people facing hunger and food insecurity, as the crisis aggravated pre-existing inequalities that were already hindering progress beforehand.25 This is due to the inflation of food prices, driven by the economic impacts of the pandemic, as well as measures taken to control it, which made healthy diets more expensive and less affordable, particularly for vulnerable groups.26 This also highlighted the challenges related to malnutrition in all forms, particularly child malnutrition, which is expected to be higher owing to the pandemic.27 In 2021 the pandemic was still prevalent and worsened in some parts of the world. The gross domestic product (GDP) of most countries globally in 2021 ‘did not translate into gains in food security in the same year’.28 The countries facing the worst of the pandemic effects continue to face enormous challenges. These are the countries with lower and more unstable income, less wealth and poorer access to critical services.29

In addition to this, the state of food security worldwide has further been affected by the war in Ukraine – an ongoing crisis as at the time of writing this article. Tension between Russia and Ukraine has been ongoing since Russia’s illegal annex of Crimea, a peninsula in Ukraine,

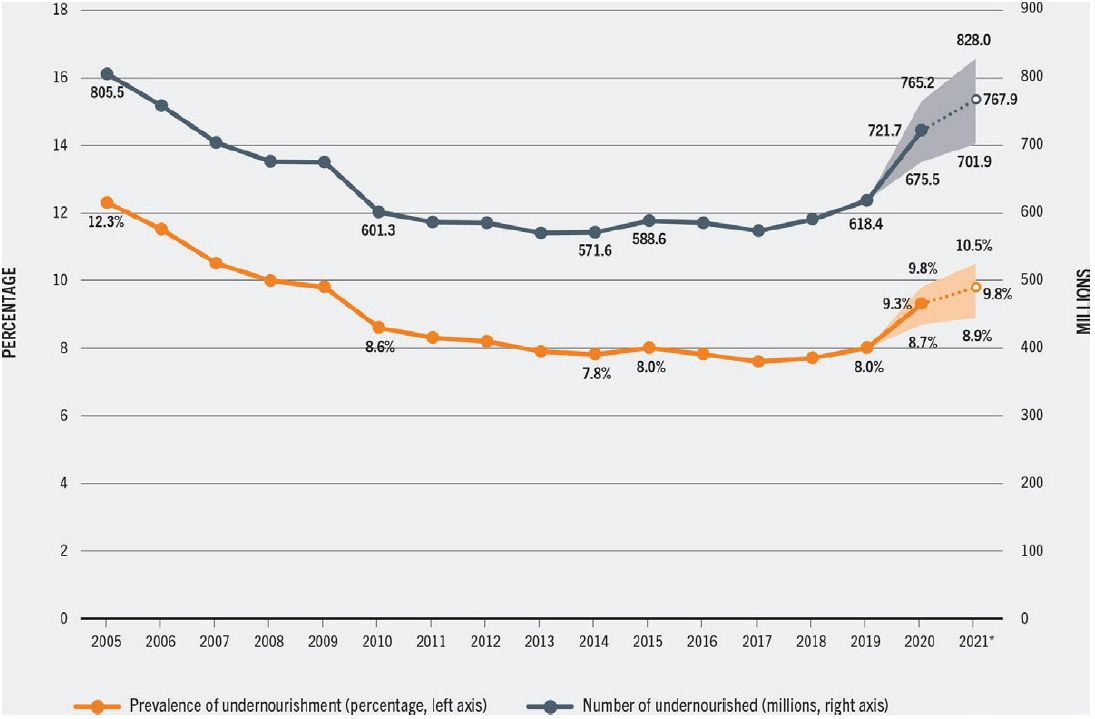

in 2014.30 The situation escalated to a full-scale war in 2022 when President Vladimir Putin sent up to 200 000 soldiers into Ukraine.31 This war has had a negative impact on the food insecurity crisis as both Russia and Ukraine are two of the most central producers of agricultural commodities in the world.32 Prior to this war, Russia and Ukraine together contributed 30 per cent and 20 per cent of all global maize and wheat products.33 They also supplied 80 per cent of all global exports of sunflower seed products.34 The war in Ukraine has led to massive disruptions in agricultural exports, exposing global food and fertiliser markets to increased risks of ‘tighter availabilities, unmet import demand, and higher international prices’.35 Numerous low-income food-deficit countries (LIFDCs), as well as those countries falling into the group of least-developed countries (LDCs), rely heavily on imported fertilisers and food stuffs from these two countries and, as such, have struggled to meet their consumption needs.36 These are some of the recent major events that have contributed to the food insecurity crisis worldwide. The diagram below reveals the prevalence of undernourishment from 2005, with projected rates for 2021:37

According to the above diagram, it can be seen that the prevalence of undernourishment was relatively unchanged from 2015, but it spiked in 2019 from 8 per cent to 9,3 per cent in 2020.38 This rise continued in 2021, although at a slower pace, to 9,8 per cent. Approximately between 702 and 828 million people globally faced hunger in 2021.39 This translates to approximately 8,9 per cent and 10,5 per cent of the world population respectively. From a global perspective, Africa suffered from hunger the most with one in five people facing hunger in 2021, as compared to ‘9,1 percent in Asia, 8,6 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean, 5,8 per cent in Oceania, and less than 2,5 per cent in Northern America and Europe’.40 In addition to this, the proportion of the population affected by hunger increased the most on the African continent.41

- Food insecurity in South Africa

There is no single standard definition for food security, as it has been described in various ways over time. There have been numerous attempts at providing a definition through research and policy usage, which has resulted in over 200 definitions having been provided in published work.42 From these definitions, certain elements of food insecurity have become apparent, namely, (i) availability; (ii) a ccessibility; (iii) affordability; (iv) nutrition; and (v) stability.

Availability refers to the supply of food in a country. Accordingly, there has to be a national supply of food that is sufficient to feed the general population. This is determined by the level of food production, net trade and stock levels.43 Accessibility refers to the ability of individuals to have access to the food that is available. This would consider the markets, general incomes, food prices and expenditures.44 This element can also refer to one’s ability to grow their own food, or fish for their food, or any other means of attaining food. In order to maintain a healthy diet, the food that is available also has to be nutritious, that is, healthy. However, food affordability is a key determinant of adequate nutrition and food security as it will determine whether one has access to nutritious foods.45 It has been defined as ‘the capacity to pay a market price for food compared to the proportion of a household’s income and other expenses’.46 These elements all have to reach stability over time, and individuals need to have access to affordable, nutritious food at all times in order for a country to be considered food secure.

South Africa is considered to be the net exporter of processed and agricultural food products, having reached the second highest level of US $10,2 billion in the year 2020 following a good production season.47 Thus, on a national level, South Africa is considered to be food secure, in that the food supply is available.48 However, food security has other aspects, as mentioned above. The lack of accessibility to nutritious foods by much of the population makes South Africa food insecure at a household level. Individuals employed in the informal sector suffer the most from food insecurity as they often experience a lack of access to welfare and social services, basic health care, and other resources necessary for their well-being.49

In 2022 the World Bank categorised SA as the most unequal country globally, the reasons for this being the missing middle class; the legacy of apartheid; racial inequalities; and highly unequal land ownership.50 It was further determined that approximately 10 per cent of the population controls 80 per cent of the wealth in South Africa.51 This further engrains the socio-economic divide in the country. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, South Africa was already considered the most unequal country in the world ‘with the rich getting richer and the poorer getting poorer’.52 The country was already facing service delivery issues, rampant crime, inequality, poverty, institutionalised corruption and high rates of unemployment.53 While the ongoing pandemic has exacerbated the issue of food insecurity, other factors, including slow economic growth, an increase in food prices and droughts, have been prevalent even prior to the pandemic.54

Measures introduced to assist in curbing the spread of COVID-19 have further affected access to food and distribution of food, with mass job losses preventing households from being able to afford the food that is accessible. This was mostly due to the nationwide lockdown. This coupled with the globalisation and socio-economic development, mentioned above, which has created a shift to unhealthy foods, has also had an impact on the consumption of nutritious foods. All these factors affect the accessibility, availability and affordability of nutritious food for households. The government’s response through legislative measures thus is important to analyse in this discussion.

- Food law and the human right to food

4.1 Food law in international law

Food law55 is a fairly recent field, with the content of the right still being unpacked. The right enjoys both national and international protection, as seen in various international agreements. Article 11(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), for instance, obligates state parties to ‘recognise the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living … including adequate food, clothing, and housing and to the continuous improvement of living conditions’.56 Article 11 further requires member states to improve on methods of production, distribution and conservation of food using scientific and technical knowledge, including the dissemination of knowledge on principles of nutrition, by developing agrarian systems to achieve the most efficient utilisation, and the development of natural resources.57 Similarly, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 (Universal Declaration) supports this right in article 25 which provides everyone with the right to a standard of living that is adequate for the health and well-being of individuals, including food.58

The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter) does not explicitly provide for the right to food. However, in the landmark decision SERAC59 the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Commission) found a violation of the right to food despite this right not being expressly recognised by the African Charter. The facts of the case are as follows: The Nigerian government was involved in oil production through the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) – a state-owned oil company that was also the majority shareholder ‘in a consortium with Shell Petroleum Development Corporation (SPDC)’.60 It was alleged that these operations led to various oil spills that contaminated the environment, against international environmental standards, and led to health problems among the Ogoni people.61 The consortium exploited oil reserves in Ogoniland, disposing toxic waste into the local waterways, and failing to maintain their facilities ‘causing numerous avoidable spills in the proximity of villages’.62 The result was the contamination of water, soil and air which had serious health impacts, ‘including skin infections, gastrointestinal and respiratory ailments, and increased risk of cancers, and neurological and reproductive problems’.63

The government was accused of condoning and facilitating these violations by placing the military and legal powers of the state at the disposal of the oil companies.64 These operations not only left thousands of villagers homeless, but food sources were also destroyed as the water bodies and soil were contaminated, where the Ogoni people relied mostly on fishing and farming for food.65 Farm animals and crops were also destroyed during raids on villages by the national security forces in an attempt to stop non-violent protests by the Ogoni people against these activities, where some individuals were also killed.66 In its decision, the African Commission linked the right to food with several other human rights including, dignity, life, health, and social and cultural development as provided for in the African Charter, and the Nigerian government was found to be in violation of these rights and others.67 In this way, although not explicitly provided for in the African Charter, the right to food finds implicit protection therein.

The right to food is further protected in other international documents where the rights of specific vulnerable groups are highlighted, for instance, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 (CRC); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 1979 (CEDAW); and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006 (CRPD). The right has further recognition in various regional documents, including the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (African Children’s Charter), 1990, and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, 2003 (African Women’s Protocol).

4.2 The right to food in South African national law

When analysing national legislation in South Africa on food law, the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Constitution) is and should be the starting point as it is the supreme law of the land. Any law or conduct that goes against the Constitution is deemed to be null and void, and all obligations imposed by it must be fulfilled.68 Chapter 2 of the Constitution contains the Bill of Rights which is defined as the ‘cornerstone of democracy in South Africa’ and enshrines the human rights of the people in the Republic, affirming the rights to freedom, equality and human dignity.69 The right to food was included in section 27(1)(b) of the Bill of Rights which provides everyone with the right to have access to sufficient food and water. Important to note here is that the right to food does not obligate the government to provide individuals with food, but that individuals need to have ‘access’ to food.

This section is to be read in conjunction with section 27(2) which provides that ‘[t]he state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of each of these rights’ including the right to food. In determining what would constitute ‘other measures’, the Constitutional Court has referred to ‘policies, programmes and strategies adequate to meet the state’s section 26 obligations’.70 The aspect of ‘progressive realisation’ of rights creates a hinderance in that it considers resource constraints that may slow down the implementation of the state’s obligations in this regard.71 During this time, the state is still tasked with laying down a ‘roadmap towards the full realisation of the right to food immediately’, and illustrating the possible efforts being made, using all available resources, ‘to better respect, protect and fulfil the right to food’.72 The Constitutional Court has attempted to unpack the meaning of the phrase in Grootboom where it provided the following:73

Progressive realisation shows that it was contemplated that the right could not be realised immediately. But the goal of the Constitution is that the basic needs of all in our society be effectively met and the requirement of progressive realisation means that the state must take steps to achieve this goal. It means that accessibility should be progressively facilitated: legal, administrative, operational and financial hurdles should be examined and, where possible, lowered over time.

In determining the content of the right to food, the Constitutional Court in Wary Holdings74 unpacked the right from the context of land, agriculture, food production and the environment, in terms of section 27(1)(b) and under international law. In its analysis, the Court recognised two elements to the right: ‘the sufficient supply of food’ which requires the presence of a national food supply which would meet the nutritional needs of the general population, and the ‘the existence of opportunities for individuals to produce food for their own use’.75 The second element requires the ability of individuals to acquire the food that is available or make use of opportunities to produce their own food.76

The Constitution also provides for the right to food in other sections, particularly when looking at specific groups. Section

28(1)(c) provides every child with the right to ‘basic nutrition, shelter, basic healthcare services and social services’. This right was addressed in the recent case of Equal Education v Minister of Basic Education77 where the suspension of the National Schools Nutrition Programme (NSNP) during the COVID-19 government lockdown was challenged.78 It was uncontended by the Court that had the NSNP programme not been suspended, 45 million meals would have been delivered per week, with no viable substitute for the NSNP for children.79

The programme benefits approximately 9 million children, all learners in quintiles 1 to 3, which represent the poorest 60 per cent of schools, thus targeting the poor and food insecure.80 The Court linked the right to a basic education, as provided by the Constitution in section 29(1)(a), with the right in section 28(1)(c) – the right of the child to a basic nutrition and the right of everyone to have access to food (section 27(1)(b)).81 Thus, the Minister and the Member of the Executive Council (MEC) were found to have violated these rights by issuing the suspension.82 The Court further elaborated on the duties of the Department of Education in relation to the right to food for children as follows:83

If there was no duty on the Department to provide nutrition when the parents cannot provide the children with basic nutrition, the children face starvation. A more undignified scenario than starvation of a child is unimaginable. The morality of a society is gauged by how it treats it children. Interpreting the Bill of Rights promoting human dignity, equality and freedom can never allow for the hunger of a child and a constitutional compliant interpretation is simply that the Department must in a secondary role roll out the NSNP, as it has been doing.

Another specific group provided for in the Constitution deals with the right to food of detainees in section 35(2)(e) which states:

Everyone who is detained, including every sentenced prisoner, has the right to conditions of detention that are consistent with human dignity, including at least exercise and the provision, at state expense, of adequate accommodation, nutrition, reading material and medical treatment.

The Court in Lee v Minister of Correctional Services84 dealt with the right in section 35. Although not dealing specifically with the aspect of nutrition or food within the right, the Constitutional Court did expound on the duty of the state in the fulfilment of the rights of detainees, which includes the provision of adequate nutrition, as follows:85

A person who is imprisoned is delivered into the absolute power of the state and loses his or her autonomy. A civilised and humane society demands that when the state takes away the autonomy of an individual by imprisonment it must assume the obligation to see to the physical welfare of its prisoner.

This implies that the state has the duty to provide detainees with the provision of nutritious food, as the state in this instance has assumed control over their autonomy.

4.3 Right to food legislation in South Africa

Aside from the Constitution, aspects of food law can be found in several pieces of national legislation including, but not limited to, the following:

- Agricultural Product Standards Act 119 of 1990;

- Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008;

- Fertilisers, Farm Feeds, Agricultural Remedies and Stock Remedies Act 36 of 1984;

- Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 54 of 1972;

- Liquor Products Act 60 of 1989;

- Marine Living Resources Act 18 of 1998;

- Meat Safety Act 40 of 2000;

- Plant Improvement Act 11 of 2018.

Each piece of legislation listed above contains different aspects relating to food law in South Africa. This creates a fragmented system, which is problematic as it could lead to a lack of uniformity regarding policy implementations as well as potential duplications. The lack of specific legislation dealing with food thus creates additional challenges in the realisation of the right to food in South Africa. In addition to this, there are three main departments responsible for the implementation of food legislation: the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF); the National Department of Health (DoH), and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). Having various departments covering issues related to food makes it difficult to ‘coordinate all the efforts of these departments’, resulting in the fragmentation of policies and activities.86

All these aspects mentioned above have an impact on the continued issue regarding NCDs in the country. Individuals need to be able to afford and access the nutritious food, which is available in the country, especially with the effects of the ongoing pandemic. A further issue would be regarding access to nutritious foods. As mentioned above, there has been a shift in dietary patterns from healthy foods to foods that, if consumed regularly, can contribute to food-related NCDs. It therefore is pertinent to analyse the protection being afforded to consumers to determine whether there is adequate protection in place.

4.4 Consumer protection in South Africa

The concept of consumer protection arose as a reaction to the unfair nature of business transactions within the law of contract. Traditionally, the notion of ‘freedom of contract’ allowed the parties to an agreement to determine the terms and conditions of a contract, and on an equal footing.87 This, however, was not the case as businesses or corporations were normally in a dominant position over the consumer, with the consumer being given ‘standard-term contracts’ on a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ basis.88 These types of contracts were drafted in favour of the business entity, and the consumer ordinarily was the vulnerable party as the products and services being offered were needed by the consumer who would thus accept terms that were unreasonable or unfair.89 Additionally, the consumers were often unable to understand the terms of the agreements, and remedies being offered provided inadequate protection for consumers.90

Due to this, social justice legislation, that is, the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 (CPA), was promulgated as a means to rectify these inequalities. The purpose of the CPA is to advance and promote the social and economic welfare of consumers in South Africa.91 The Act aims to promote fair business practices, establish a fair legal framework for the development of a fair consumer market, with a particular focus being placed on ameliorating the disadvantages experienced by particular vulnerable groups, including low-income persons; minors; seniors; illiterate persons; those living in isolated or remote areas; and those living in low-density population areas.92

The Act further provides protection of certain fundamental rights under chapter 2, some of which emulate the fundamental rights in the Bill of Rights in the Constitution. The fundamental rights under the CPA include the following:

- the right of equality in the consumer market;93

- the consumer’s right to privacy;94

- the consumer’s right to choose;95

- the right to disclosure and information;96

- the right to fair and responsible marketing;97

- the right to fair and honest dealings;98

- the right to fair, just and reasonable terms and conditions;99 and

- the right to fair value, good quality and safety.100

These rights highlight the importance the Act places on consumer safety and protection. Important to this discussion is the aspect of labelling of food products. This is because certain vulnerable groups may be unable to understand the labels on food products and may inadvertently purchase a product that could result in possible harm. It is imperative for the average consumer to understand the information on food items, which also forms part of the right to disclosure and information. Section 22 of the CPA requires the supplier to ensure that any ‘notice, document or visual representation’ being displayed to a consumer should be in plain language.101 Such a representation or, in this case, a label, will be considered to be in plain language if one can reasonably conclude that an ordinary consumer of the class of persons for which the label is intended, with minimal consumer experience and average literacy skills, can understand the content and significance of the label.102

In considering the information that needs to be included on labels, in this instance food labels, pertinent basic information is required that is necessary for the consumer to be able to make an informed choice.103 This would include ‘the number, quantity, measure, producer information, place or country of origin, ingredients, allergens, contact information and trademarks’, depending on the type of goods.104 The CPA further prohibits suppliers from applying descriptions on labels that would be misleading to consumers, including the intentional altering, defacing, removal, covering or obscuring of information with the purpose of said misleading.105 Examples of this would include changing expiration dates on perishable goods and/or leaving out allergens on products which could result in serious health issues.106 The importance of labelling was prevalent during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, where illicit ad counterfeit goods were on the rise in the market, and suppliers removing expiration dates on products including canned foods.107

The labelling of food products goes hand-in-hand with marketing and advertisements. As mentioned above, consumers often lack the ability to interpret labels. This lack of knowledge and support is exploited by suppliers and manufacturers in the food industry to promote food products in a manner that is not conducive to nutrition.108 Historically speaking, challenges involving labelling and advertisements faced by consumers in South Africa include promoting health claims through brand names; food manufacturers making nutrient and health claims on labels and advertising; labels and advertising that were misleading; the lack of nutritional information and specifications on labels; and advertising of ‘unhealthy foods’, particularly by restaurants and food companies.109 This, coupled with the low literacy skills and inequality in South Africa, has the result of contributing to inaccurate food choices.110 This inevitably has an effect on the rise of NCDs in the country.

4.4.1 Proposed new regulations – Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs

In response to the problems associated with the labelling and advertisements of food, the Department of Health released the Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs (Draft Regulations)111 in January 2023 for public comment. While not passed as at the time of writing this article, the document aims to make changes to the way in which food products are being labelled and advertised at stores nationwide. One of the propositions being made relates to prohibited statements. Accordingly, certain statements, reflected on both food labels and advertisements, which would create the impression that the product has been supported or endorsed according to recommendations by certain entities, that is, certain practising health professionals, would be prohibited.112 Endorsement entities related to NCDs would be required to be actively involved in generic health promotion activities promoting the reduction of NCDs, and would have to be ‘free from influence by, and not related to the supplier’ of a particular foodstuff.113

Additionally, the draft regulations also aim to prohibit the use of certain words and phrases that could be seen as ‘trendy’, for instance, words such as ‘wholesome’, ‘nutritious’, ‘nutraceutical’ or ‘super-food’, ‘smart’ or ‘intelligent’, or any comparable pictorials or logos with similar meanings that would imply that the food is superior in some way.114 This would include placements of this nature on the name and tradename.115 Labels or advertisements which purport that the foodstuff provides balanced or complete nutrition would also be prohibited according to the Regulations.116 Furthermore, in an attempt to curb misleading statements or descriptions on foodstuffs, the use of words or phrases such as, but not limited to, ‘grass-fed’, ‘grain-fed’, ‘Karoo lamb’, ‘country reared’, ‘natural lamb’, ‘free range’ and so forth, are permitted to be reflected on pre-packaged labelling and advertising of these goods only if the ‘descriptor is linked to a specific protocol which is approved or registered with the Department of Agriculture, or regulated in terms of the Agricultural Product Standards Act’.117

Where a food product is not regulated under the Agricultural Product Standards Act, statements indicating that the food product is, among others, ‘natural’, ‘fresh’, ‘nature’s’, ‘traditional’, ‘original’, ‘authentic’, ‘real’, ‘genuine’, ‘home-made’, or any other similar words or phrases with a similar meaning would be permitted provided such statement is in accordance with criteria provided for in certain guidelines published on the DoH website.118

The Draft Regulations further discuss marketing restrictions for foodstuffs that would not be permitted to be advertised to children. The packaging, labelling or advertising of foodstuffs would be prohibited from depicting any reference made to celebrities, cartoon characters, sport stars, computer animations or any similar type strategy.119 Reference made to competitions, tokens or collectable items that appeal to children, and would inspire unhealthy eating, would also be prohibited.120 In this same light, any portrayals of ‘positive family values’ on labels or packages that would ultimately encourage excess consumption of a foodstuff, undermine healthy, balanced diets, promote an inactive lifestyle, be promoted as a food replacement, or leave out undesirable aspects of the food’s nutritional content would also be prohibited.121

Important to note further is that the Draft Regulations also introduce mandatory ‘front-of-pack labels’ (FOPLs) to be visible on food products where the product contains added sugar, added saturated fat, added sodium and also where the product exceeds the ‘nutrient cut-off values for total sugar, total sodium or total saturated fatty acids’ or contain artificial sweeteners.122 Nutrient cut-off values, as well as artificial sweeteners, are listed as follows in the Draft Regulations:123

|

Nutrient cut-off values |

|

|

Nutrient |

Value indicated in nutritional information table |

|

Total sugar(s) in g |

Solids: ≥ 10.0g per 100g |

|

Liquids: ≥ 5.0g per 100ml |

|

|

Total Saturated fatty acids in g |

Solids: ≥ 4.0g per 100g |

|

Liquids: ≥ 3.0g per 100ml |

|

|

Total Sodium in mg |

Solids: ≥ 400mg per 100g |

|

Liquids: ≥ 100mg per 100ml |

|

|

Artificial sweeteners |

|

|

Contain any added artificial sweetener |

Bear the applicable logo warning as per Annexure 10124 |

Annexure 10 of the Draft Regulations provides elements of the FOPL. Accordingly, should the above nutrient cut-off values be exceeded, the product would be required to carry a warning label as follows:125

The Draft Regulations thus appear to address concerns surrounding misleading labels and advertisements, among other issues. It has been reported that nearly 80 per cent of pre-packaged foodstuffs sold in South African supermarkets are ‘highly processed or ultra-processed, containing excessive amounts of added sugars, salt, unhealthy fats and chemical additives’ which tend to make the products more flavoursome.126 This has led to an increase in NCDs, as discussed above, and, thus, the Draft Regulations appear to be a move in a more positive direction in battling these issues. However, this also poses an additional cost to companies as these will be forced to relabel most of their products and redo advertisements for various foodstuffs. The Draft Regulations are likely to come into effect in the year 2025 according to the Global Health Advocacy Incubator, Mr Philip Mokoena.127

4.4.2 Cons to the Draft Regulations

The Draft Regulations aim to regulate the marketing, packaging and promotion of food products in South Africa. While they are important for promoting transparency, preventing misleading claims, and assisting in reducing the number of NCDs in the country, they do pose a few challenges. For instance, compliance with the labelling requirements discussed above could pose an additional financial burden, particularly for small businesses, and/or businesses conducted in rural areas. This involves costs for new packaging (where the FOPL would be necessary), as well as testing the products to ensure that they comply with these labelling requirements.

Questions surrounding the enforcement of these regulations may also be raised, particularly in the rural and/or under-resourced areas. This could potentially lead to non-compliance going unnoticed, with some businesses evading the rules without facing consequences. One could further argue that in these instances, certain parts of the population may lack access to nutritional information of certain foods, hindering their ability to make informed food choices. Since the draft regulations aim to, among others, lessen instances of NCDs in South Africa, this would mean that the rural population would still be at a higher risk, and lack access to nutritious food, affecting their food security.

Furthermore, the Draft Regulations fail to fully accommodate illiterate consumers. Despite the enhanced visibility of nutritional information through FOPL, the reliance on text-based labelling may still exclude those who cannot read. While visual cues, such as the warning labels pictured above, would be helpful, the needs of illiterate consumers –who may struggle to interpret even the most clearly-written labels – remain largely unaddressed. Research should be conducted into ways of making the Regulations more inclusive in this manner.

While it is commendable that the government has released these Regulations to the public, and they seem poised to contribute to reducing NCDs in South Africa if implemented, the fact that they have yet to be passed and have undergone four revisions raises concerns surrounding public trust. It may foster a perception of a lack of transparency in decision making, government instability, and/or incoherent policy processes. This could also potentially suggest that the government may be uncertain about its own policies, which can result in public confusion, making it difficult for individuals to stay informed about evolving proposals, grasp their implications, and offer meaningful feedback.

4.4.3 Current Regulations – Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs, 2010

The Current Regulations in place are the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 54 of 1972: Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs, R146 (current Regulations).128 The main differences between the Regulations in place and the Draft Regulations discussed above refer to the FOPL, nutrient profiling system, marketing to children, and so forth. Perhaps the most pertinent difference between the two would be the FOPL, which is mandatory according to the Draft Regulations,129 but not mentioned in the Current Regulations. Accordingly, nutritional information is typically placed on the back or side of the food packaging, which makes it less visible and accessible to consumers at a glance according to the Current Regulations.

A further change viewed in the Draft Regulations is the inclusion of a nutrient profiling system which is not included in the Current Regulations. Section 51(1)(c) of the Draft Regulations provides a profiling model for foodstuffs, where a comprehensive system is in place to assess the overall nutritional profile of a food product. Such a system is not included in the Current Regulations.

With regard to information on allergens, the Current Regulations make it mandatory to provide this information on the ingredient list of foodstuffs, as per section 43. However, it is rather generalised, focusing on common allergens with a mention of uncommon allergens. Alternatively, the Draft Regulations call for enhanced labelling requirements and stricter rules relating to allergens, including more detailed descriptions of allergens and potential cross-contamination risks as viewed in sections 37 to 42.

A distinction is also prevalent where sugars are involved. Under the Current Regulations, ‘added sugar’ is defined in section 1, and a total sugar content is required to be listed in the nutritional information panel of a food product. However, no clear distinction is given or required for naturally-occurring sugars (such as those in fruits and dairy) and added sugars (such as table sugar or high-fructose corn syrup). This means that consumers are informed of the total sugar content, but cannot identify how much comes from added sugar as opposed to naturally-occurring sugars. The Draft Regulations require this distinction to be made clear and each to be listed separately on food packaging. Section 51(1)(a) requires a FOPL to be added where added sugar occurs in the food product, as discussed above.

Perhaps one of the most important distinctions for purposes of this discussion would be the element of marketing. The Current Regulations are somewhat limited in this regard, focusing primarily on ensuring truthful and non-misleading advertising.130 The Draft Regulations, on the other hand, propose stricter advertising restrictions, particularly for products marketed to children. This includes restrictions on promoting high-sugar, high-fat, or high-salt foods in media targeted at children, as well as the use of cartoons or characters that appeal to young audiences in product marketing.131

5 Other initiatives

There have been several initiatives made on an international level to attempt to address the prevalence of NCDs. The WHO implemented the ‘WHO Best Buys’ – a document that provides policy makers with a list of recommended interventions to address NCDs.132 Regarding diet-related NCDs, the document highlights enabling actions, including the implementation of WHO recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children, and implementing the global strategy on diet, physical activity and health.133

The UN General Assembly has over the years further issued numerous declarations in an attempt to tackle the issue of NCDs. While declarations are not binding on member states, they still provide guidelines that can be considered by states, including South Africa, in the implementation of legislation and policies aimed at tackling NCDs.134

On a more national level, the National Consumer Commission (NCC) is the body established by section 85 of the CPA tasked with enforcing the rights of the consumer. This body has successfully mediated over a few cases concerning the rights of consumers. An example of this, dealing with the misleading of consumers generally speaking, would be the Unicity Trading case.135 Accordingly, the NCC found that Unicity Trading had misled consumers by failing to disclose significant information regarding their car’s history and condition. Consumers should be encouraged to make use of the NCC for food-related issues where the CPA is involved.

6 Conclusions and recommendations

Food security has several aspects to it, including availability, accessibility, affordability, and the nutritional value of food. Although considered to be food secure on a national level, South Africa is ‘at home’ food insecure, as a large portion of the population are unable to access the food that is available in the country. The socio-economic divide in the country also attributes to several inequalities in this regard, with low-income level individuals and other vulnerable groups experiencing the worst of the food insecurity issues. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated this divide as numerous people had to endure job losses, which further prevented households from being able to afford and/or access food. Globalisation and the socio-economic development in South Africa have also had the added effect of individuals moving from healthier food options to those that are high in salt, sugar and trans-fats, contributing to food-related NCDs.

Although a fairly recent concept, the right to food is a right that has to a large extent been endorsed on an international, regional and national level. As mentioned above, we find different implementations of the right to food in international conventions, such as ICESCR, the Universal Declaration and also regionally in the African Charter, even if not explicitly mentioned, but can be deduced from case law as seen in SERAC discussed above. Various other documents provide for the right to food for specific vulnerable groups as seen in CRC, CEDAW and CRPD. This highlights the importance of the right to have access to food, particularly from a human rights perspective. Food law, particularly in South Africa, has a fragmented system regarding the policies and activities surrounding food, which creates a lack of uniformity and duplications.

Moving away from accessibility, consumer protection deals with ensuring that business entities do not exploit vulnerable individuals who may not fully understand the terms of agreements, preventing them from agreeing to terms that are unreasonable or unfair. This article focused on the instance of labelling requirements and advertisements, and their importance particularly regarding food products. The implementation of the CPA attempts to curb these instances by advancing and promoting the social and economic welfare of consumers, with a particular focus on low-income persons, minors, seniors, illiterate persons, those living in isolated or remote areas, and those living in low-density population areas. Food labels, for instance, need to be displayed in plain language, and not be intentionally misleading. Regardless, the COVID-19 pandemic still brought with it an influx of illicit and counterfeit goods, with some having expiration dates tampered with. Instances of this nature can lead to consumers ingesting foods where the nutritional value is compromised, leading to further instances of NCDs.

In their evaluation of NCDs in the Caribbean, Webb and Conrad suggest a way of targeting unhealthy dietary habits, by raising taxes on fast food and implementing legislation that targets foods high in trans fats.136 They further suggest incentives to be included at a community level by governments aimed at incentivising physical exercise, for instance, by removing taxes on gymnasiums.137 A more equitable system surrounding health care should further be investigated, with policies being put in place to improve the quality of health care.138 Considering the fragmented food law system in South Africa, and taking into account the high levels of food insecurity in the country, it would be beneficial for a single piece of legislation being implemented that focuses solely on food systems in the country, as well as having only one governmental department dealing with aspects relating to food, as a means to prevent potential instances of duplication, confusion and a lack of uniformity on policy implementations.

The government appears to be making attempts to rectify the problem surrounding NCDs through the Draft Regulations on labelling and advertising of foodstuffs discussed above. By having FOPL warning labels on product packaging and reflected in their advertisements, the average consumer will be more capable of making informed food choices, as they will be more aware of the content of the product and be knowledgeable on the fact that it exceeds the nutrient cut-off values in a way that is understandable to the lay person. The Draft Regulations further aim to counter corporate exploitation in the food industry, and ultimately protecting the public health. Should the Draft Regulations be signed into law, misleading words and phrases would also be prohibited even further than currently is the case, hopefully preventing companies and corporations involved in the food industry from taking advantage of consumers, and ultimately reducing the rate of NCDs in the country.

The Current Regulations differ substantially from the proposed Draft Regulations. The Current Regulations focus on general labelling requirements but lack key elements that are proposed in the Draft Regulations. These include the FOPL, introducing a nutrient profiling system to assess the overall nutritional value of food products, and the addition of stricter allergen requirements for food products labelling. Important to note is also the proposed imposition of stricter restrictions on marketing, particularly to children, limiting the promotion of unhealthy foods and the use of child-appealing characters. Although more inclusivity could be made available for illiterate consumers, as mentioned above, this comparison highlights the positive and potentially transformative impact the Draft Regulations could have should they be passed into law.

However, this is yet to be seen as it is important to note that the current Draft Regulations are the fourth version to be released to the public this year, with the latest released in April 2023. The problem with this is that it creates the perception of a lack of transparency in decision making, instability within the government, a lack of coherent decision making, or evidence that the government is uncertain about its own policies. This can further lead to confusion among the public as it becomes challenging for individuals to keep up with the evolving proposals, understand the implications, and provide meaningful input and feedback. It is crucial for governments to strike a balance between making necessary revisions and ensuring transparency, stability and effective public participation.

-

1 This is evident from its inclusion in numerous human rights instruments, including, but not limited to, art 11 of the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966, as well as ch 2, sec 27(1)(b) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Ch 2 contains the human rights or fundamental rights of South Africa.

-

2 WHO ‘Malnutrition – Key facts’ (2021), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed 24 March 2023).

-

3 As above.

-

4 As above.

-

5 As above.

-

6 M Manafe and others ‘The perception of overweight and obesity among South African adults: Implications for intervention strategies’ (2022) 19 International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 1.

-

7 WHO ‘Noncommunicable diseases’ (2021), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed 7 June 2022).

-

8 D Rozanska and others ‘Dietary patterns and the prevalence of non-communicable diseases in the PURE Poland Study participants’ (2023) 15 Nutrients 2.

-

9 WHO (n 7).

-

10 As above.

-

11 E Samodien and others ‘Non-communicable diseases – A catastrophe for South Africa’ (2021) 117 South African Journal of Science 1.

-

12 As above.

-

13 K Reddy ‘Food products and non-communicable disease: Implications of the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008’ (2018) 3 Journal of South African Law 569.

-

14 As above.

-

15 Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 54 of 1972: Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs, R.3337 (Draft Regulations).

-

16 Reddy (n 13) 570.

-

17 As above.

-

18 As above.

-

19 Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) ‘Hunger and food insecurity’, https://www.fao.org/hunger/en/ (accessed 9 June 2021).

-

20 As above.

-

21 African Union ‘Agenda 2063: The Africa we want’ Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2014).

-

22 Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

(25 September 2015) UNGA A/70/L 1. -

23 UNGA (n 22).

-

24 UNGA (n 22) para 2.1.

-

25 FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2022 (2022). FAO ‘Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable’ 9, https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0639en (accessed 9 June 2021).

-

26 FAO (n 25) 47.

-

27 FAO (n 25) 9.

-

28 As above.

-

29 As above.

-

30 ‘Has Putin’s war failed and what does Russia want from Ukraine?’ BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56720589 (accessed 3 March 2023).

-

31 As above.

-

32 FAO (n 25) 20.

-

33 As above.

-

34 As above.

-

35 FAO (n 25) 20.

-

36 As above.

-

37 FAO (n 25) 13.

-

38 FAO (n 25) 11.

-

39 As above.

-

40 FAO (n 25) 13.

-

41 As above.

-

42 W Peng & E Berry ‘The concept of food security’ (2019) 2 Encyclopaedia of Food Security and Sustainability 1.

-

43 World Bank ‘What is food security?’, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-update/what-is-food-security (accessed 28 March

2023). -

44 As above.

-

45 World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) ‘Food Affordability – The role of the food industry in providing affordable, nutritious foods to support healthy and sustainable diets’ 2022 5, https://www.wbcsd.org/Programs/Food-and-Nature/Food-Land-Use/FReSH/Resources/Food-Affordability-The-role-of-the-food-industry-in-providing-affordable-nutritious-foods-to-support-healthy-and-sustainable-diets (accessed 9 June 2022).

-

46 As above.

-

47 W Sihlobo ‘South African riots and food security: Why there’s an urgent need to restore stability’ The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/south-african-riots-and-food-security-why-theres-an-urgent-need-to-restore-stability-164493#:~:text=South%20Africa%20is%20generally%20a,following%20a%20favourable%20production%20season (accessed 9 June 2022).

-

48 As above.

-

49 V Mlambo & N Khuzwayo ‘COVID-19, food insecurity and a government response: Reflections from South Africa’ (2021) 19 Technium Social Sciences Journal 2.

-

50 World Bank ‘Inequality in Southern Africa: An assessment of the Southern African customs union’ (2022), https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099125303072236903/pdf/P1649270c02a1f06b0a3ae02e57eadd7a82.pdf#page=14 (accessed 1 September 2024).

-

51 As above.

-

52 Mlambo & Khuzwayo (n 49) 2.

-

53 As above.

-

54 As above.

-

55 The Food and Agricultural Organisation has defined food law as applying to ‘legislation which regulates the production, trade and handling of food and hence covers the regulation of food control, food safety, quality and relevant aspects of food trade across the entire food chain, from the provision for animal feed to the consumer’. See FAO ‘Food laws and regulations’, https://www.fao.org/food-safety/food-control-systems/policy-and-legal-frameworks/food-laws-and-regulations/en/ (accessed 1 September 2024).

-

56 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1996.

-

57 Art 11(2)(a) ICESCR.

-

58 Art 25(1) Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948.

-

59 Social and Economic Rights Action Centre (SERAC) & Another v Nigeria (2001) AHRLR 60 (ACHPR 2001) (SERAC).

-

60 SERAC (n 59) para 1.

-

61 As above. The Ogoniland is a kingdom in Nigeria that covers approximately 1 000 square kilometres in Southern Nigeria. According to the 2006 national census, the area has a population of about 832 000 Ogoni people, who predominantly are fishermen and farmers. See UN Environment Programme ‘About Ogoniland’, https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/disasters-conflicts/where-we-work/nigeria/about-ogoniland (accessed 10 June 2022).

-

62 SERAC (n 59) para 2.

-

63 As above.

-

64 SERAC (n 59) para 3.

-

65 SERAC (n 59) paras 8-9.

-

66 As above.

-

67 SERAC (n 59) para 64.

-

68 Sec 2 Constitution.

-

69 Sec 7(1) Constitution.

-

70 Government of the Republic of South Africa & Others v Grootboom & Others 2001 (1) SA 46 (CC) para 40.

-

71 OHCHR & FAO ‘The right to adequate food’ (2010) 19, https://www.ohchr.

org/en/publications/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-no-34-right-adequate-food (accessed

10 June 2022). -

72 As above.

-

73 Grootboom (n 70) para 45.

-

74 Wary Holdings (Pty) (Ltd) v Stalwo (Pty) Ltd (2008) ZACC 12.

-

75 Wary Holdings (n 74) para 85.

-

76 As above.

-

77 Equal Education v Minister of Basic Education 2021 (1) SA 198 (GP).

-

78 The NSNP is a government programme that provides one nutritious meal to all learners in poorer primary and secondary schools with the objective to provide nutritious meals to leaners in order to improve their ability to learn. See South African Government ‘What is the National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP)?’ https://www.gov.za/faq/education/what-national-school-nutrition-programme-nsnp (accessed 14 June 2022).

-

79 Equal Education (n 77) para 24.

-

80 Equal Education (n 77) para 32.

-

81 Equal Education (n 77) para 34.

-

82 As above.

-

83 Equal Education (n 77) para 53.

-

84 Lee v Minister of Correctional Services Case CCT 20/12.

-

85 Lee (n 84) para 17.

-

86 E Durojaye & E Chilemba ‘The judicialisation of the right to adequate food: A comparative study of India and South Africa’ (2017) 43 Commonwealth Law Bulletin 272.

-

87 Reddy (n 13) 576.

-

88 As above.

-

89 As above.

-

90 As above.

-

91 Sec 3 CPA.

-

92 As above.

-

93 Sec 8 CPA.

-

94 Secs 11-12 CPA.

-

95 Secs 13-21 CPA.

-

96 Secs 22-28 CPA.

-

97 Secs 29-39 CPA.

-

98 Secs 40-47 CPA.

-

99 Secs 48-52 CPA.

-

100 Secs 53-61 CPA.

-

101 Sec 22(1) CPA.

-

102 Sec 22(2) CPA.

-

103 J Barnard ‘An overview of the consumer safety and product liability regime in South Africa’ (2021) 9 International Journal on Consumer Law and Practice 36.

-

104 As above.

-

105 Secs 24(2)(a)-(b) CPA.

-

106 Barnard (n 103) 36.

-

107 As above.

-

108 Reddy (n 13) 574.

-

109 As above.

-

110 As above.

-

111 Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 54 of 1972: Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs, R.3337 (Draft Regulations).

-

112 Sec 9(1) Draft Regulations (n 112).

-

113 Sec 9(1)(a)(iii) Draft Regulations.

-

114 Sec 9(1)(e) Draft Regulations.

-

115 As above.

-

116 Sec 9(1)(f) Draft Regulations.

-

117 Sec 42(1) Draft Regulations; Agricultural Product Standards Act 119 of 1990 (Agricultural Products Standards Act).

-

118 Sec 42(2) Draft Regulations (n 112).

-

119 Sec 52(1)(b)(i)(aa) Draft Regulations.

-

120 Sec 52(1)(b)(i)(bb) Draft Regulations.

-

121 Sec 52(1)(b)(i)(cc) Draft Regulations.

-

122 Sec 51(1) Draft Regulations.

-

123 Sec 51(1)(c) Draft Regulations.

-

124 Secs 91-92 Draft Regulations.

-

125 Annexure 10 Draft Regulations.

-

126 A Sulcas ‘Draft regulations aim to make warning labels on unhealthy foods mandatory by 2025’ The Daily Maverick, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-02-02-draft-regulations-aim-to-make-food-warning-labels-mandatory-by-2025/ (accessed 30 March 2023).

-

127 As above.

-

128 Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act 54 of 1972 – Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs, R 146 2010 (Current Regulations).

-

129 Sec 51 Draft Regulations (n 112).

-

130 Sec 47 Current Regulations (n 128).

-

131 Secs 2(3)(c), 51(5)(c) & 52 Draft Regulations (n 112).

-

132 World Health Organisation ‘”Best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases’ Geneva (2017), https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf (accessed 30 March 2023).

-

133 WHO (n 132) 10.

-

134 Examples include United Nations General Assembly Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (2012) A/RES/66/2; United Nations General Assembly Outcome Document of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Comprehensive Review and Assessment of the Progress Achieved in the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (2014) A/RES/68/300; and United Nations General Assembly Political Declaration of the Third High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (2018) A/RES/73/2.

-

135 Unicity Trading (Pty) Ltd t-a Cape SUV and The National Consumer Commission & 3 Others Case A76-2024.

-

136 M Webb & D Conrad ‘Public expenditure on chronic non-communicable diseases in the Caribbean: Does it matter?’ (2017) 8 Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences 35.

-

137 As above.

-

138 As above.