Alice Storey

LLB (Hons) PG Dip LLM PhD (Bimingham City University)

Senior Lecturer in Law and Associate Director, Centre for Human Rights, College of Law, Social and Criminal Justice, Birmingham City University, United Kingdom

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4810-6133

Alice.Storey@bcu. ac.uk

I wish to thank Dr Damian Etone and Dr Philip Oamen for their helpful comments, and to the organisers and attendees of the UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna 1993 – Strengthening Imperatives 30 Years After’ for the interesting discussions on themes of this article. A further thank you to Nicola Stevens and Aise-Osa Igbinomwanhia for their research assistance.

Edition: AHRLJ Volume 25 No 1 2025

Pages: 302 - 331

Citation: A Storey ‘The United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review and female genital mutilation in Somalia: The value of civil society recommendations’ (2025) 25 African Human Rights Law Journal 302-331

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2025/v25n1a12

Download article in PDF

Summary

Female genital mutilation is a violation of international human rights law and a public health concern. The Federal Republic of Somalia has the highest prevalence of FGM across the world, with an estimated 97 to 99 per cent of women and girls having undergone FGM. Worldwide, various strategies are being implemented seeking to eliminate FGM, including criminalisation, further education, and involvement of civil society organisations. The role of CSOs, through the United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review mechanism, is the key focus of this article. Somalia’s three UPR cycles to date are analysed, identifying (i) how frequently member states and CSOs recommend on similar themes; and (ii) whether CSOs’ and/or member states’ recommendations on FGM are sufficiently formulated to aid implementation by Somalia. Following this analysis, I argue that CSO recommendations do hold some value for member states, but to achieve success in the context of eradicating FGM in Somalia, improvements must be made by both CSOs submitting stakeholder reports with recommendations included, and member states making recommendations within the UPR. Specific proposals are made, which could be utilised by CSOs and member states when preparing for Somalia’s fourth cycle review scheduled for 2026.

Key words: international human rights; Universal Periodic Review; female genital mutilation; Somalia

1 Introduction

Female genital mutilation (FGM) – also referred to as ‘cutting’ – is a public health issue that violates international human rights.1 The Federal Republic of Somalia has the highest prevalence of FGM across the world, with an estimated 97 to 99 per cent of women and girls having undergone FGM.2 Various strategies are being implemented worldwide seeking to eliminate FGM, including criminalisation, further education and involvement of civil society organisations (CSOs). The role of CSOs, through the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) mechanism of the United Nations (UN), is the key focus of this article.

The UPR is a peer-review mechanism of the Human Rights Council which cyclically reviews all 193 member states’ protection and promotion of human rights. It involves input from governments, UN bodies and CSOs acting as ‘stakeholders’. A core feature of the UPR is the recommendations process, where other UN member states make recommendations to the state under review regarding how to better promote and protect human rights on the ground. Whereas CSOs cannot make recommendations formally, they can – and do – provide recommendations in their stakeholder reports, submitted in advance of each state review.

To understand the value of these CSO recommendations within the UPR regarding FGM in Somalia, this article assesses Somalia’s three cycles of UPR to date – from 2011, 2016 and 2021. To do this, I collated all recommendations related to FGM from CSOs and member states, coding them according to each recommendation’s theme. Thereafter, I analysed the recommendations through two questions: (i) how frequently member states and CSOs recommend on similar themes; and (ii) whether CSOs’ and/or member states’ recommendations on FGM are sufficiently formulated to aid implementation by Somalia. Following this analysis, I argue that CSO recommendations do hold some value for member states, but to achieve success in the context of eradicating FGM in Somalia, improvements must be made by both CSOs submitting stakeholder reports with recommendations included, and member states making recommendations within the UPR. Specific proposals are made, which could be utilised by CSOs and member states when preparing for Somalia’s fourth cycle review scheduled for 2026.

Part 2 of the article provides an overview of FGM in Somalia, relevant international, regional and domestic laws, and current strategies for eradicating FGM. Part 3 begins by outlining what the UPR is and the method adopted in this article. It then proceeds to detail the analysis and findings of the study. Part 4 concludes the study and recommends next steps for utilising the UPR, and in particular CSO recommendations, as a viable strategy for eliminating FGM in Somalia.

This is the second in a three-part series of articles assessing (i) the formulation of UPR recommendations;3 (ii) the value of civil society UPR recommendations; and (iii) the implementation of UPR recommendations, through the lens of eliminating violence against women.

2 Female genital mutilation in Somalia

FGM is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as ‘all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons’.4 There are four types of FGM: type 1, which involves the total or partial removal of the clitoral glans and/or the clitoral hood; type 2, which includes the total or partial removal of the clitoral glans and labia minora, with or without the labia majora being removed; type 3, referred to as infibulation, where the vaginal opening is narrowed through creating a seal; and type 4 which covers all other, non-medical procedures performed on female genitalia.5

FGM is a historical practice, dating back almost 5 000 years.6 It is now considered a global abuse of women’s rights that is performed across the world, although predominantly in the Middle East and African countries, including Somalia.7

Somalia is situated in the Horn of Africa with a population of approximately 17 million people.8 Somalia has a federal structure, including five federal states, plus Somaliland, and its legal system is comprised of civil, Islamic and customary law.9 Since it gained independence from British and Italian colonisation in the 1960s, Somalia has been embroiled in civil war and political turmoil.10 In 1991, during civil unrest in the country, Somaliland declared itself to be an independent country, although this has not been formally recognised by the UN or African Union (AU).11 Puntland, one of the five federal states, was declared an autonomous state of Somalia in 1998.

Somalia has the highest rate of FGM across the world, as estimates indicate that 97 to 99 per cent of women and girls have undergone some form of the practice,12 including girls as young as two years.13 The most common method is type 3 FGM, infibulation, which is referred to in Somalia as pharaonic circumcision.14 However, in Somaliland, reports indicate a move from type 3 to type 1 FGM, although Powell and Yussuf note that this shift is more prevalent in urban than in rural areas.15 A study undertaken in the Hargeisa and Galka’ayo districts found that the vast majority of participants continue to support the use of FGM,16 and across Somalia, Johnson-Agbakwu and others found that women still strongly support FGM,17 which is out of kilter with many other countries.18

FGM in Somalia is considered a cultural, traditional and religious practice,19 where zero tolerance eradication efforts can be viewed as Western ideals encroaching on cultural traditions.20 Indeed, Onsongo asks who gets to define a person’s culture as ‘barbaric’,21 and Cassman has argued that ‘[i]f the focus is truly on a solution, and not on the imposition of Western beliefs on African cultures, then this solution must reconcile how on one hand FG[M] is a torturous, painful, barbaric practice, while on the other hand, it is a practice that lies at the heart of cherished tradition, value, and honour’.22 This is particularly relevant to African countries such as Somalia, as Gele and others note that in such cultures, FGM ‘represents the central component of a traditional rite of passage ceremony in which girls are expected to pass through a transition from puberty to adulthood’.23 Often, parents must make difficult decisions whether to subject their daughters to FGM, or abandon traditional, cultural practices. Moreover, while there is a widespread belief in Somalia that religion requires FGM,24 whether religions, in particular Islam and Christianity, require the perpetration of FGM is contentious and contemporary views are moving away from a link between the two.25

FGM is also linked to an idea of ‘femininity, modesty, and sexuality’.26 However, this presents a misogynistic, heteronormative and outdated view of women’s sexuality, indicating that FGM is a form of sexual control over women, presuming that heterosexual marriage is the ultimate goal for women and without FGM they will be regarded as unsuitable for marriage.

The reality is that FGM provides no medical benefit to the women and girls on whom it is performed but, in fact, is more likely to lead to physical and psychological complications, up to and including death.27 For example, type 1 procedures can involve ‘excruciating pain, resulting in complications such as haemorrhage, trauma to nearby structures, and failure to heal’.28 According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the involvement of medical professionals does not improve the safety of FGM, contrary to common misconceptions.29 Studies have shown a link between negative pregnancy or childbirth outcomes and FGM. For example, evidence from the Somalian diaspora in Norway showed ‘that perinatal complications, such as foetal distress, emergency caesarean sections, and prelabour deaths, were more frequent among infibulated Somali women (with type 3) compared to Norwegian women’.30 These medical complications have financial implications for states, as the WHO demonstrates current and future economic costs of FGM-related health care through its FGM Cost Calculator. The WHO found that annual FGM health care costs across 27 countries ‘totalled 1,4 billion USD during a one-year period’.31

Somalia also has legal obligations regarding the practice of FGM in the country, which the following parts consider.

2.1 Somalia’s legal obligations: International human rights

International human rights law, both substantive and customary, prohibits FGM on the grounds that it breaches the rights of women and girls.32 The perpetration of FGM violates multiple, well-established human rights principles. This includes the right to life;33 the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment;34 and the right to health,35 all of which are substantiated by global human rights treaties, namely, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT); and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) respectively. Somalia has ratified all three treaties.36

Article 24(3) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) expressly directs states to ‘take all effective and appropriate measures with a view to abolishing traditional practices prejudicial to the health of children’.37 Somalia became a party to CRC in 2015, leaving just one country in the world that has not ratified it.38 Further provisions of CRC, including a child’s right to privacy,39 protection from discrimination based on sex,40 and protection from violence, injury or abuse,41 are also relevant.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is applicable to the prevention of violence against women, including FGM.42 Somalia has neither signed nor ratified CEDAW, and Williams argues that this ‘may also suggest that the country’s political activity and traditions need to evolve from a legislative perspective’.43 The treaty bodies attached to CRC and CEDAW have provided joint general recommendations regarding FGM, most recently in 2019, noting the link between FGM being a violation of both women’s and children’s rights, and that both bodies are committed to preventing, responding to and eliminating practices including FGM.44

The UN and its subsidiary bodies have been taking action against FGM in earnest since 1997, when the WHO, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) issued a joint statement.45 A growing number of policies have emerged since, including the UNFPA and UNICEF’s Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in 2007, the WHO’s 2010 Global strategy to stop healthcare providers from performing FGM, and the first evidence-based guidelines on the management of health complications from FGM, jointly authored by the WHO, UNFPA and UNICEF in 2016. Also, in 2022 the WHO launched a training manual for healthcare providers to challenge and assist in the prevention of FGM. The UN General Assembly has found that FGM constitutes ‘irreversible abuse that impacts negatively on the human rights of women and girls’.46 This signifies a positive collaboration between UN entities, and it can be argued that prohibiting FGM is emerging as customary international law.

2.2 Somalia’s legal obligations: Regional law

Somalia is a member state of the regional group, the African Union (AU). The AU takes a clear stance towards the eradication of FGM, solidifying the regional view that this practice is a form of gender-based violence.

Somalia ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter) in 1985,47 meaning that the country should adhere to its provisions. Although the African Charter does not directly reference the elimination of FGM, multiple other provisions can be construed to support this, including article 16, which guarantees the right to physical and mental health, article 4 which affirms the right to life and integrity of the person, and article 18 which protects the rights of women and children.

Somalia signed the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (African Women’s Protocol) in 2006 but has not ratified it.48 This is concerning, given that, among others the African Women’s Protocol provides vital protections related to FGM. Article 5 provides that ‘state parties shall take all necessary legislative and other measures’ to eliminate ‘all forms of harmful practices which negatively affect the human rights of women and which are contrary to recognised international standards’, including ‘prohibition, through legislative measures backed by sanctions, of all forms of female genital mutilation, scarification, medicalisation and para-medicalisation of female genital mutilation and all other practices in order to eradicate them’.49 Other provisions are also relevant, for example, article 14 which protects the health and reproductive rights of women in Africa, which includes the prevention of FGM.

The African Union Initiative on Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation Programme and Plan of Action 2019-2023 (Saleema Initiative) was put in place as part of Africa’s Transformative Agenda 2063 which seeks to

advocate for accelerated action at African Union member states level for protection and care of young girls and women towards zero cases of female genital mutilation by 2030. It will involve prioritising a comprehensive package of interventions, including high level interventions on policy and legislative action, domestic financial resource allocation, and service delivery as well as a community engagement for social norms change through a holistic approach, and creating a new cultural narrative to address the underlying gender gaps and inequalities that drive the practice of female genital mutilation in the communities most affected, across the continent and globally.50

While there is a particular focus on those AU states with a high prevalence of FGM, it appears that the Saleema Initiative has had limited impact in Somalia. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic saw a rise in FGM in Somalia, as girls were ‘subjected to door to door FGM’ as the ‘lockdown [was] seen as an opportune time for the procedure to be carried out in the home with ample time for healing’.51

2.3 Somalia’s legal obligations: Domestic law

Following the disorder in Somalia and 12 years of planning, the Provisional Constitution of the Federal Republic of Somalia was put in place in 2012,52 as amended in 2016. The Provisional Constitution prohibits ‘any form of violence against women’ in article 15(2). Article 15(4) specifically states that ‘female circumcision is a cruel and degrading customary practice, it is tantamount to torture. The circumcision of girls is prohibited.’53 Despite this, there is no legislation that criminalises FGM or sets out punishments for the perpetration or assistance in the perpetration of FGM in either Somalia or Somaliland. While there is a provision in the Somali Penal Code that criminalises causing hurt to another, which carries a carceral sentence if found guilty, it does not specifically refer to FGM.54 Moreover, both Somalia and Somaliland have protections against child abuse and neglect, which can be interpreted to include FGM, but these protections do not explicitly refer to FGM.55

In 2021 a group of civil society organisations (CSOs) participating in Somalia’s third cycle UPR, found that while ‘the government launched a number of policies’ including an FGM Bill, ‘many of these policies are drafts and [have] not [been] enacted or implemented’.56 This suggests the need for new approaches and further work.

2.4 Strategies for eradicating female genital mutilation in Somalia

UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 aims to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, setting a target to eliminate FGM globally by 2030 through SDG target 5.3.57 There are multiple proposals for achieving this and, while passing legislation criminalising FGM is important, I contend that this alone will not eradiate the practice. World Health Assembly Resolution WHA61.16 from 2008 stressed ‘the need for concerted action in all sectors: health, education, finance, justice and women’s affairs’.58 Adigüzel and others have argued that ‘further efforts and research from different countries, cultures, beliefs, organisations, and individuals, focusing on knowledge, awareness, legalisation, opinions of lay and religious leaders, particularly including women’s rights activists, and women with FGM/C, are needed to stop FGM/C’.59 This appears to be particularly important for Somalia, in that it may benefit from a multi-faceted strategic approach to eliminating FGM, as well as an inter-generational approach to achieve eradication, involving all generations and levels of the family. A sensitive approach must be taken when considering the eradication of FGM in Somalia, where the practice is seen as a social norm that is often performed to ensure social acceptance.60 A human rights-based approach to ending the practice of FGM must also consider the cultural context to avoid challenges in implementing an eradication strategy. This part considers some of the existing and proposed strategies for the eradication of the practice.

Criminalisation, through domestic legislation, can assist with the elimination of FGM. This can include criminalising not only the cutting itself, but also those who fail to report FGM61 and cross-border FGM.62 Nabaneh and Muula argue that ‘while criminalisation may not be the best means of stopping FGM, it creates an enabling environment to facilitate the overall strategy of African governments in eradication of the practice’.63 However, while many countries – not including Somalia – have criminalised the practice, to ensure full eradication of FGM, I suggest that the law must be complemented by a structure to implement and enforce such laws.

Healthcare providers are well-placed to support the eradication of FGM, as the WHO recommends that healthcare sectors should take a comprehensive approach to preventing FGM through resources and guidance, including supporting countries to adapt resources to fit local contexts.64 However, Nabaneh and Muula found that, in some African countries, this approach ‘unintentionally leads to numerous parents and relatives seeking safer procedures, rather than abandoning the practice’ in its entirety.65 Conversely, Population Council’s research in Somaliland showed that ‘[p]ositive attitudes towards abandoners [of FGM] arose mainly from health care workers who encouraged abandonment of FGM[] due to the health complications experienced by girls’.66 This suggests that healthcare workers can be part of a multi-faceted approach to eliminating FGM, but with clear guidance and support towards eradication that takes into account the nuances of Somalia’s cultural context.

Education is a fundamental tool to seeking the elimination of FGM. A study on healthcare workers and their understanding of FGM in Australia identified that education must be culturally sensitive and involve both men and women.67 Cultural sensitivity is particularly important in the Somalian context, as set out in part 2.1. Strategies for eliminating FGM must consider how education can be used as a tool to change mindsets from FGM being a traditional practice, to a violation of women’s and children’s rights to be free from violence. Culturally-sensitive education and reorientation could be of benefit, especially when targeted and tailored for different audiences, including families and wider communities, as well as local leaders.68 There are examples of how this can lead to positive outcomes. For example, in Malawi, ‘chiefs are leading efforts to informally adopt community laws towards addressing harmful practices’, including FGM.69 While not legally binding, the status of traditional leaders lends weight to these community laws, something that could be implemented as a stepping stone towards Somalia passing formal legislation to criminalise FGM. To get there, educating traditional leaders on FGM, alongside local communities, and pointing to success stories such as that of Malawi, are necessary first steps. Somalia’s Provisional Constitution already provides the legal basis to do this, protecting the right to education in article 30 and the protection of the country’s culture in article 31. Converging these two protections, while also learning from success stories such as that in Malawi, would be a vital step towards reorientation and changing mindsets on FGM in Somalia.

Although it is women and girls who suffer FGM, men can play a vital role in moving towards the abandonment of the practice as fathers, husbands and traditional leaders.70 Varol and others conducted a systematic review of all articles published between 2004 and 2014 regarding the attitudes of men towards FGM. They found that ‘[m]any men wished to abandon this practice because of the physical and psychosexual complications to both women and men’, but that ‘[s]ocial obligation and the silent culture between the sexes were posited as major obstacles for change’.71 The study revealed that the higher the level of education, the more likely men would support the abolishment of FGM, underscoring the importance of culturally-sensitive education.72 Varol and others suggest that ‘[a]dvocacy by men and collaboration between men and women’s health and community programmes may be important steps forward in the abandonment process’.73 Gele and others proposed that the ‘best possible way to achieve a successful change is to accomplish a convention shift of intermarrying communities and a public declaration that marks the shift, in which every family understands that [FGM] is harmful’.74

A further suggestion for eliminating FGM is ‘the idea of an “alternative ritual”, which exclude[s] genital cutting but maintain[s] the ceremony and the public declaration for community recognition’.75 This appears to have worked well in Kenya,76 as well as in The Gambia, Senegal, Uganda and Tanzania.77 Gele and others suggest that a similar approach that is tailored to the Somalian community’s understanding of the practice is essential for the eventual eradication of FGM in Somalia.78

Civil society is a key driver for action in terms of eradicating FGM. There are examples of this in Somalia. For instance, ‘Save the Children and partners are supporting local non-governmental organisations in modifying cultural perceptions of cutting as central to girls’ rites of passage and in finding alternate ways to elevate the status and value of women in the family and community’.79 Moreover, since 1996, the African Women’s Organisation has worked tirelessly to educate communities on FGM and support victims in African communities, including in Somalia.80

The UN’s UPR can add to these strategies for eradicating FGM, by providing a mechanism that brings together the views and suggestions from governments, UN bodies and civil society, both globally and in Somalia. There is the opportunity to put forward suggestions for a multi-pronged approach to elimination, covering all strategies discussed above and more, while also involving civil society in discussions and strategies.

3 Somalia’s UPR: Civil society and member state recommendations on female genital mutilation

3.1 The United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review

Created in 2006, the UPR is an innovative mechanism of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), which cyclically reviews all 193 UN member states’ human rights protection and promotion every four and a half years. Each review is based on the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Universal Declaration), international human rights treaties, voluntary commitments made by states, and relevant humanitarian law.81 The process is a ‘peer-review’ by other state delegations, and also involves civil society’s input. Each review is recorded in publicly-available documentation. This starts with the preparation of three documents that underpin each review: the National Report, prepared by the state under review, and the Compilation of UN Information and Summary of Stakeholders’ Information, both of which are compiled by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

CSOs play a vital role in the UPR, acting as ‘stakeholders’ throughout the process. This is underscored by UNHRC Resolution 5/1, which makes it clear that the UPR should ‘[e]nsure the participation of all relevant stakeholders, including non-governmental organisations and national human rights institutions’.82 A key role of CSOs within the UPR process is for them to submit stakeholder reports, which Resolution 5/1 states should include credible and reliable information. CSOs can submit single stakeholder reports, or can collaborate with other CSOs to make a joint submission, on human rights issues in the state under review. The OHCHR then summarises these reports into a 10-page document. As the summary report is one of the three reports that underpins every state’s UPR, the stakeholder submissions are a core part of the mechanism.

The review itself takes place in the UNHRC, wherein the state under review and other states engage in an interactive dialogue. As part of this, recommendations are provided by UN member states regarding how the state under review can better protect and promote human rights. Once the review has taken place, and the member state recommendations have been made, proceedings are written up by the OHCHR and a troika of supporting states into the Report of the Working Group. As part of this, the state under review will decide whether to accept or note each of the recommendations – with noted recommendations signalling a de facto rejection. The report of the Working Group will thereafter be adopted at a UNHRC plenary session. Finally, the accepted recommendations should be implemented by the state under review, with progress on implementation forming the basis of the next review. States may also submit a mid-term review, halfway between cycles, updating on their progress.

CSOs can also participate in the UPR pre-sessions, which are organised by a leading non-governmental organisation (NGO), UPR Info, and take place at the Palais des Nations one month before the review. This provides CSOs and other stakeholders the opportunity to inform member state delegations about the human rights situation in the state under review, supporting the creation of meaningful recommendations.

The UPR has achieved success in attracting one hundred per cent cooperation from member states to date, with the fourth cycle of reviews having commenced in November 2022. Somalia has been reviewed three times: in 2011, 2016 and 2021, with cycle four scheduled to take place in 2026.

3.2 The UPR and female genital mutilation

Previous studies have been conducted on African states’ participation in the UPR. For example, Smith’s assessment of engagement with the first cycle of the UPR concluded that ‘African states comment repeatedly (usually positively) on other African group states’.83 Etone’s study confirmed this finding, proposing that a softer approach to recommendations could lead to better engagement regarding contentious issues.84 Specifically regarding FGM at the UPR, a further analysis by Etone suggested that ‘reframing female genital mutilation as a technical, health issue rather than a normative human rights concern can advance the human rights issue as internal to the African culture’.85

Gilmore and others conducted a study on the UPR and sexual and reproductive health and rights, which includes FGM, finding that the UPR ‘can be a valuable mechanism for reviewing governments’ performance’ on this issue.86 Patel’s evaluation of the issue of FGM within the first cycle of the UPR discovered that ‘states under review were overtly defensive in their responses [to recommendations on FGM] as they either referred to existing laws and policies that were already in place, or justified the continuance of the practice on cultural grounds’.87 Whereas Gilmore and others’ research found that, in the first seven sessions of cycle two of the UPR, ‘implementation of [FGM-related] recommendations included legal and policy reforms, the establishment of prevention strategies, and investments in programmes to address the issue’,88 providing a positive example of implementation in Burkina Faso.

Existing work suggests that the UPR can have a positive impact on the issue of FGM, if a suitable approach to engaging with the mechanism is taken by all key actors. One possible way of achieving this is through amending the way in which member states formulate their recommendations.

3.3 UPR recommendations

Recommendations are the core focus of this article. Given the importance of this part of the UPR process, it is imperative that it operates to its full potential, that is, stronger recommendations will lead to more positive actions on the ground and, ultimately, better human rights promotion and protection globally. My previous work has considered the formulation of UPR recommendations and how member states can improve these to have the most impact on the ground.89 In that article, I suggested that member states should look to CSOs to guide them as, ideally, CSOs should ‘provide their expertise’ and member states should ‘use their template recommendations during the UPR’.90 This article builds upon this, by examining the value of CSO recommendations to member states. CSOs, acting as stakeholders within the UPR, do not formally provide recommendations during a review, but they can – and indeed are encouraged to91 – provide recommendations in their individual stakeholder reports.

Literature has identified that information provided by stakeholders in their reports have been made use of by member states. For instance, Etone’s examination of recommendations made on transitional justice found a link between CSO information provided in individual reports and member state recommendations on transitional justice in South Sudan.92 Moreover, McMahon and others’ study of the first cycle UPR concluded that ‘recommendations do in fact reflect perspectives and themes contained in recommendations of ‘CSOs, but that they were “framed in more general terms than those proposed by CSOs”’.93 McMahon and others’ study has built the foundations for arguing that CSO recommendations are valuable to member states. This article seeks to use this foundation to focus in on the role of CSO recommendations in terms of eliminating FGM, to understand whether the recommendations provided by CSOs during Somalia’s UPRs are being identified and used by member states in practice.

3.4 Method

To provide an empirical analysis of recommendations made by both CSOs and member states to Somalia on FGM, I followed Etone’s approach to analysing UPR recommendations on a specific human rights issue.94 I first collated all recommendations from the first three cycles of Somalia’s UPR in 2011, 2016 and 2021. I identified CSO recommendations by reading through all individual stakeholder submissions by CSOs in the three cycles of review. I then collated all member state recommendations, along with responses from Somalia, from the reports of the Working Group and their Addendums.

I restricted the collection of recommendations to include only those that referred explicitly to FGM, female circumcision, cutting, or any other synonym used to describe FGM.95

I then coded the recommendations according to each recommendation’s ‘theme’, that is, what the particular focus of the recommendation was in relation to FGM. Nine themes were identified from the coding of CSO and member state recommendations, namely, (1) legislative reform; (2) implementation of laws;

(3) adoption of measures related to FGM; (4) development of a national action plan; (5) culture and tradition; (6) funding for FGM eradication; (7) education; (8) eradication of FGM; and (9) raising awareness of FGM. Where a recommendation discusses multiple gender-based violence issues, it was only coded to the relevant theme in relation to the FGM section of the recommendation. Moreover, where a recommendation could be categorised into more than one theme, it was allocated to the clearest theme. For example, Iran’s recommendation to ‘[t]ake all necessary legal and practical measures to eliminate FGM, including considering amendments to the penal code with provisions to specifically prohibit this practice’96 was categorised into the ‘legislative reform’ theme, as the clearest part of the recommendation asked Somalia to amend its Penal Code.

Following the thematic coding, I engaged in a desk-based examination of all recommendations, using the following two questions to guide my analysis: (i) how frequently member states and CSOs recommend on similar themes; and (ii) whether CSOs’ and/or member states’ recommendations on FGM are sufficiently formulated to aid implementation by Somalia. These questions are addressed in the analysis below.

It should be noted that the findings of this study can only be attributed to the issue of FGM in Somalia. However, the study could be replicated for other countries and forms of violence against women and girls, to identify trends and formulate wider conclusions.

3.5 Analysis: Context

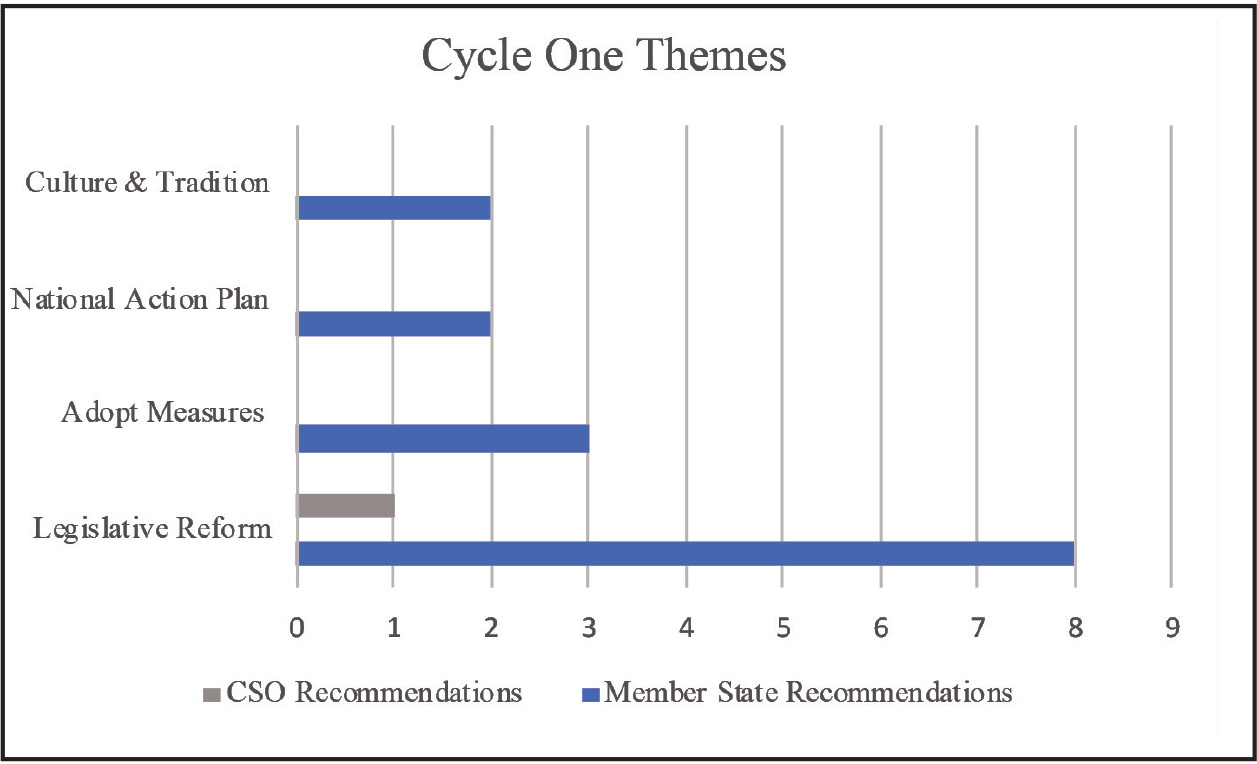

Somalia’s first cycle UPR took place on 3 May 2011. In terms of stakeholders, 26 organisations submitted reports, of which seven specifically referred to FGM.97 However, of the seven, only one stakeholder made a recommendation on FGM, under the theme of ‘legislative reform’.98 Compare this with member state recommendations. In cycle one, Somalia received 155 recommendations in total, 15 of which referred explicitly to FGM.99 These recommendations were coded into four themes: legislative reform (eight recommendations);100 adopt measures related to FGM (three recommendations);101 develop a national action plan (two recommendations);102 and culture and tradition (two recommendations).103

Figure 1

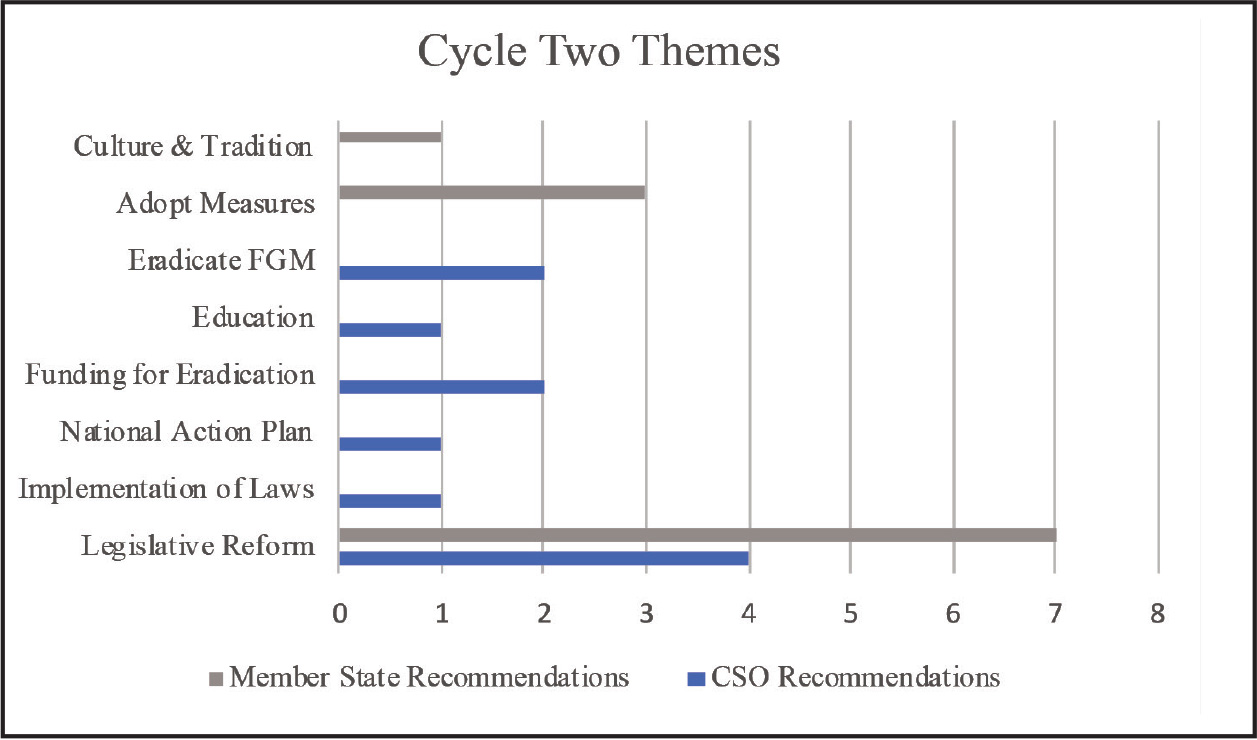

The second UPR of Somalia was held on 22 January 2016. Sixteen stakeholders submitted reports to cycle 2. While, overall, this was fewer than in cycle one, there was a noted increase in joint submissions, which are encouraged by the OHCHR ‘when the stakeholders focus on issues of similar nature’.104 Joint submissions are also permitted to use double the word limit when compared to an individual submission, increasing the word count from 2 815 to 5 630,105 allowing more detail to be included by stakeholders. Five of the 16 reports included specific references to FGM106 and, importantly, each of these five stakeholders also made 11 recommendations on FGM, covering six themes between them, a major improvement from the stakeholder recommendations in cycle one. The themes covered were legislative reform (four recommendations);107 implementation of laws (one recommendation);108 developing a national action plan (one recommendation);109 funding for FGM eradication (two recommendations);110 education (one recommendation);111 and eradicating FGM (two recommendations).112 Member states provided 228 recommendations in total to Somalia during cycle two, with 11 specifically referring to FGM.113 These recommendations were coded to three themes: legislative reform (seven recommendations);114 adopting measures related to FGM (three recommendations);115 and culture and tradition (one recommendation).116

Figure 2

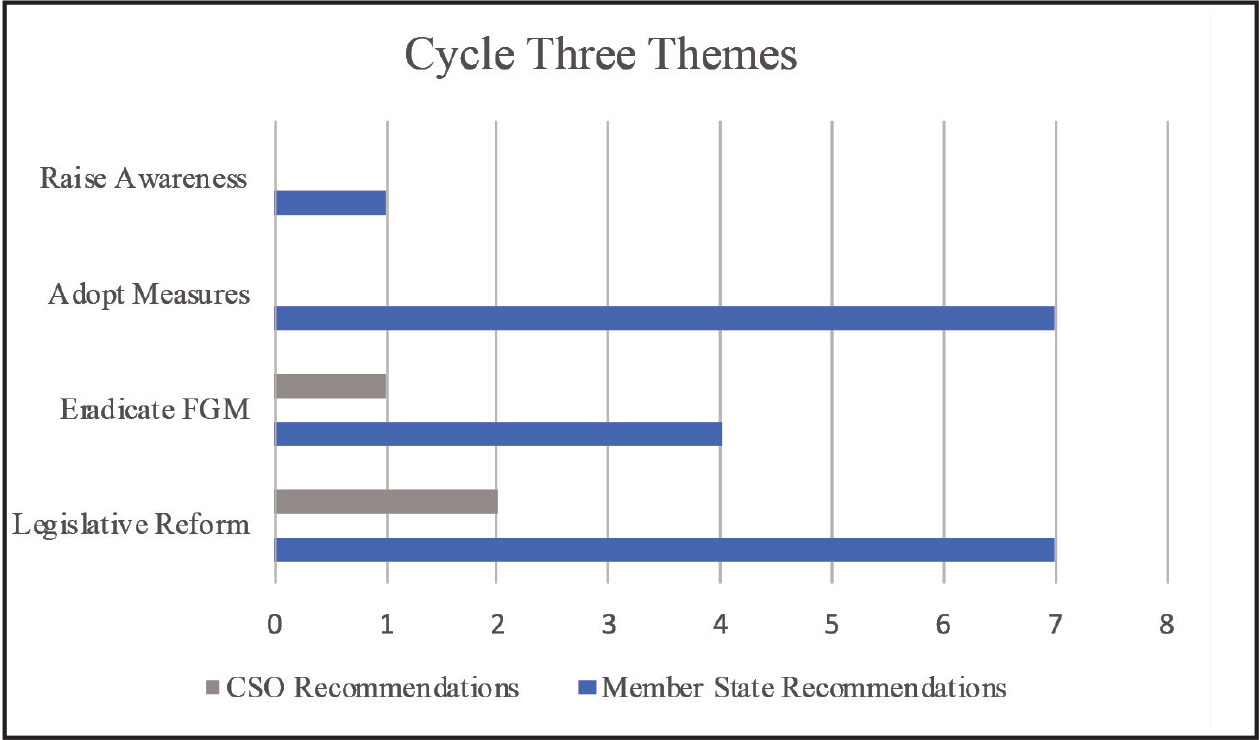

Somalia’s most recent UPR, cycle three, took place on 6 May 2021. Thirty stakeholders submitted reports, with eight of those directly referring to FGM.117 However, only three of these reports provided three recommendations on FGM, under two themes: legislative reform (two recommendations)118 and eradicating FGM (one recommendation).119 Compare this with member state recommendations. Out of the 273 recommendations received in total, 19 referred specifically to FGM, under four themes: legislative reform (seven recommendations);120 adopting measures related to FGM (seven recommendations);121 eradicating FGM (four recommendations);122 and raising awareness of FGM (one recommendation).123

Figure 3

3.6 Analysis: Findings

This part of the article outlines the findings, guided by the two key questions set out in the method section: (i) how frequently member states and CSOs recommend on similar themes; and (ii) whether CSOs’ and/or member states’ recommendations on FGM are sufficiently formulated to aid implementation by Somalia.

3.6.1 Frequency of thematic recommendations from CSOs and member states

Across Somalia’s three cycles of review, the data shows that there are only two converging themes between CSO and member state recommendations regarding FGM: (i) legislative reform, across all three cycles; and (ii) the eradication of FGM, in cycle three. It appears that this is a missed opportunity for CSO recommendations to positively influence that of the member states, particularly because CSOs appear to be making recommendations on more substantive themes than member states. For example, in cycle two, CSOs raised the themes of funding for eradicating FGM and education, whereas member states did not identify these same themes across any of the three cycles. These were important recommendations, for example, MPV had suggested that Somalia should ‘[a]llocate sufficient funding for the launch of a community outreach initiative that raises awareness of the health consequences of FGM/C’.124 TDF recommended on the importance of investing in education and improving on ‘gender imbalance’ within the education sector in Somalia.125 These themes can be linked back to the strategies for eradicating FGM identified earlier in this article, indicating that CSOs are well placed to provide information and recommendations based upon their expertise and engagement on the ground. Yet, member states did not use these seemingly valuable recommendations. This suggests that, in relation to FGM in Somalia, CSOs are not successfully impacting member state recommendations. This does not confirm the findings of McMahon’s study on cycle one, suggesting that while, broadly, CSO recommendations are valuable to the UPR, when doing a deep dive into the detail of specific thematic human rights issues, there is less success. Further studies are required on this, to identify whether other issues in other states’ UPRs are seeing a better uptake of CSO recommendations on certain issues.

There is an existing opportunity for CSOs to positively impact on member state recommendations, through the UPR pre-sessions. The pre-sessions take place prior to the review, in Geneva, and provide a panel of stakeholders the opportunity to present a statement to member states, which includes model recommendations for member states to use.126 I have experienced the benefit of engaging with the pre-sessions and the pre-UPR advocacy, as I have engaged in the pre-sessions of multiple countries on behalf of the UPR Project at BCU. For example, in October 2020, the UPR Project submitted a report to Namibia’s UPR, focusing on the rights of women and girls with HIV. This report received significant attention and citations from the UN in its Stakeholder Summary document.127 In March 2021 I was invited to be a panellist for Namibia’s UPR pre-session, where I discussed the core issues relating to the rights of women and girls with HIV with UN member states and other CSOs. After engaging in this advocacy, during Namibia’s third cycle UPR it received three specific recommendations on women and girls, using the information provided by the UPR Project at BCU.128 This was a significant improvement as it had received zero recommendations in the previous UPR cycle, when HIV/AIDS recommendations were broad and bracketed all people living with HIV together, ignoring their intersectional experiences.

While this experience was impactful, the advocacy took place online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. My UPR Project colleagues had further success in terms of our recommendations positively influencing that of member states, when engaging with the pre-sessions in person in Geneva, for the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland’s cycle four review in 2022. After speaking at the pre-session, having in person meetings with government delegations, and taking part in the ‘informal exchange of views with EU member states’, member states used the UPR Project’s recommendations during the UK’s fourth cycle review.129 The conclusion of the UPR Project team is that, ‘whilst all our stakeholder submissions have been cited by the OHCHR, in order to truly influence member state recommendations stakeholders must engage in advocacy prior to the Working Group session’.130 This approach may also benefit CSOs working on the issue of eradicating FGM in Somalia.

3.6.2 CSO and member state recommendations: Are they sufficiently formulated to aid implementation by Somalia?

The low frequency of member states recommending on similar themes as CSOs could be explained, at least in part, by the formulation of CSO recommendations. A prominent criticism of the UPR mechanism is the broad nature of recommendations from member states.131 The SMART approach is generally considered the most sensible – specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timebound.132 The reason for SMART recommendations is essentially to aid the state under review with implementation.133 If CSO recommendations are to have value to member states when they are formulating their own recommendations, they must take the SMART approach in order to assist all key actors to support implementation domestically.

There are examples of recommendations within Somalia’s UPRs that are well-designed and follow a SMART approach, and others that could be improved. For example, legislative reform was a common theme for both CSOs and member states across all three cycles. Such recommendations included ‘[a]mend the Penal Code to prohibit the practice of female genital mutilation’ (Canada, cycle one)134 and ‘FGM law is to be drafted’ (JS5, cycle two).135 Canada’s recommendation arguably is more persuasive, as it provides a specific action to take in terms of legislative reform, namely, amending Somalia’s Penal Code to criminalise FGM, a much-needed action to begin the multi-faceted process of eradication. JS5’s recommendation is too broad to be relied upon during the implementation phase, as it does not detail what the law should cover, or how it could be enacted in practice. MPV’s cycle two recommendation perhaps was more persuasive, as it called on Somalia to ‘[a]mend the Penal Code with provisions to prohibit the harmful practice of FGM/C and ensure effective implementation, particularly in terms of prevention, awareness-raising, monitoring and sanctions’.136 Although this is more specific in the type of legislative reform required, it could be strengthened by providing detail on how this could be achieved by the Somalian government.

Moreover, an issue with legislative reform, more generally, is that, as has been seen in other countries with a high prevalence of FGM, even when laws have been passed criminalising FGM, the practice has long continued.137 A possible solution to this is recommending on implementation of such laws in practice, as was seen in cycle two by TDF, which noted that while legislation by itself will not lead to the eradication of FGM,138

there is need to enforce implementation of laws, even those provided by the constitution of Somalia. Constitutional laws must not remain paper work, as the case is. They are drawn in order to be effective in protecting the inhabitants of Somalia, women and children inclusive. Gender discriminations for example are covered in the national constitution, and must be as well implemented.139

Yet, even this lacked specificity to encourage implementation. Such recommendations should also focus on how laws on FGM can be implemented in practice, giving practical suggestions and solutions to be tried and tested by the Somalian government.

Similarly, in cycle three, both CSOs and member states recommended on the theme ‘eradicate FGM’. IADP proposed that Somalia should ‘make more efforts to eliminate female genital mutilation that is rampant in Somali society’,140 and Poland advised to ‘[e]radicate harmful practices such as female genital mutilation’.141 However, FGM in Somalia is too complicated an issue to simply suggest that Somalia should ‘eliminate’ or ‘eradicate’ it. If member states are to use CSO recommendations as a template, as I argue they should, then CSO recommendations must be formulated in such a way that aids implementation on the ground. I have previously argued that, when making recommendations related to violence against women, member states should take an intersectional approach.142 This would make clear to the government that women are not just one homogenous group, that they experience violence and discrimination differently depending upon their differing characteristics. This also applies to FGM in Somalia. CSOs should use their vast knowledge on this issue to formulate SMART and intersectional recommendations for member states to use.143

Often, CSOs include very relevant and intersectional information in the text of the reports but do not provide SMART recommendations based on that information. For example, in cycle three, JS7 provided the following on FGM in Somalia:144

[M]any young girls in Somalia are victims of female genital mutilation (FGM), which is a harmful traditional practice that causes serious harm, health implications and in certain cases even leads to the death of a child or complications during childbirth at a later age. The existing mechanisms and systems to protect children in Somalia are inadequate and do not meet the required international standards. This is most dire in remote rural areas, where there is a lack of health services to save lives. The government has promised during the past two UPR cycles to sustainably address these issues and provide services to the most vulnerable. Although some small progresses have been booked, there are still significant shortages of life saving systems and provisions for children in Somalia.

This provided vital information, particularly related to the intersectional experiences of women in rural areas and the needs of vulnerable women regarding FGM. However, JS7’s recommendation suggested that Somalia should ‘[e]nact FGM law’.145 JS7 could have used their in-depth knowledge of the issues to present intersectional recommendations that Somalia should consider, accept and implement, with JS7 being able to keep track of implementation, assessing this in its submission to the next cycle.

Equally, CSOs should be tactical in how they approach the UPR. As noted above, joint submissions of stakeholder reports can be extremely beneficial. However, in collaborating on joint submissions, CSOs should not lose focus of key human rights themes. For instance, in cycle 3, JS7 was comprised of 126 CSOs, yet made just one recommendation on FGM, most likely because of word limit constraints. Perhaps, instead, JS7 could have co-ordinated multiple joint submissions between the 126 CSOs, ensuring that all key human rights issues were covered in detail. For example, one of these reports could have been solely focused on FGM, ensuring that this issue was covered more effectively, by making SMART and intersectional recommendations.

This is especially important because Somalia’s government has to date been receptive to UPR recommendations related to FGM. For example, in cycle one, in accepting recommendations related to FGM, the government noted:146

The harmful practice of FGM is very widespread in Somalia and almost all Somali women and girls are subjected to this damaging practice (see paragraphs 52-53, UPR National Report). Somalia will take all necessary measures including legal measures, educational awareness campaigns, and dialogue with traditional and religious leaders, women’s groups and practitioners of FGM to eliminate the practice of FGM and other forms of violence against women. Somalia is committed to amend its penal code with provisions explicitly prohibiting the practice of FGM. Somalia seeks technical and financial assistance from fellow member States and calls upon the international community to share good practices in eradicating FMG that can be applied to Somalia.’

While this was a positive response, it is clear from the further two UPR cycles that little action has been taken by the government. One indicator as to why this is the case was shown in cycle two. In response to Uruguay’s recommendation to ‘[m]ake all necessary efforts to pass legislation prohibiting female genital mutilation within the current year’,147 the Somalian government noted this, stating that ‘[c]onsidering the limited capacity of the government it will not be able to fulfil this recommendation in the current year’.148 It accepted other recommendations asking for legislative reform, but they did not provide a timescale as Uruguay did, indicating that Somalia is open to the idea of prohibiting FGM but is reluctant or unable to take action imminently. CSOs should consider this, as well as Somalia’s response in cycle one, which called upon the international community to provide ‘technical and financial assistance’ and ‘to share good practices in eradicating FGM.’ CSOs – and member states – should focus their submissions and, importantly, their recommendations on these points in order to genuinely support Somalia’s attempt to eradicate FGM, considering what action could be taken to persuade Somalia to make immediate changes to law and practice regarding FGM. As the UPR is cyclical, it is vital that key actors are considering what has happened in previous cycles and shaping their engagement accordingly, as well as understanding the requirement for a multi-faceted approach to eradicating FGM.149

4 Conclusions and next steps

This is the second in a three-part series of articles assessing (i) the formulation of UPR recommendations;150 (ii) the value of civil society UPR recommendations; and (iii) the implementation of UPR recommendations, through the lens of eliminating violence against women. The overarching aim of this three-part series of articles is to improve the implementation of UPR recommendations which, in turn, will advance the protection and promotion of human rights domestically, particularly for women and girls. This study has considered the value of CSO recommendations for member states regarding the eradication of FGM in Somalia. To date, opportunities have been missed for CSO recommendations to positively influence that of the member states.

In terms of lessons to be learned from the outcome of this study, there are three key points. First, CSOs should lead by example and provide SMART and intersectional recommendations within their stakeholder reports, making them more valuable to member states. There is a wealth of work suggesting the need for SMART recommendations and, if member states are to use CSO recommendations, CSOs using the SMART format will encourage states to follow the same structure. In readiness for Somalia’s next UPR, CSOs should use their vast knowledge on the issue of FGM to not only provide this information in stakeholder submissions, but also to provide SMART and intersectional recommendations on the issue.

Second, once CSOs have started to use SMART recommendations in their stakeholder submissions, they should then encourage member states to use these. One way to do this is by attending the UPR pre-sessions, hosted by UPR Info, and engaging in advocacy prior to the review, as demonstrated by the UPR Project at BCU’s – and many other CSOs’ – successes. For those CSOs that are unable to travel to Geneva, advocacy via email and online meetings is an alternative, along with considering partnering with other organisations who may be able to provide this support.151

Third, CSOs are encouraged to be tactical when submitting reports and joint submissions. The UN-mandated word limits on reports are very strict, so being strategic on how to make this work is vital. CSOs should not gloss over important human rights issues – it would be better to consider one theme in detail rather than ten points with minimal information and vague recommendations. As noted above, where there are a large number of CSOs providing one joint submission, it may be more prudent to split the CSOs into smaller groups, submitting a higher number of joint submissions that focus on different human rights issues in detail.

So far, this series of articles has provided multiple suggestions for member states to improve their recommendations, and the value of CSO recommendations in terms of violence against women and girls. The next article will now focus on the final stage of the UPR process, where those recommendations should be implemented in practice to better protect and promote human rights, by assessing implementation of UPR recommendations on FGM.

-

1 A Gele, BP Bø & J Sundby ‘Have we made progress in Somalia after 30 years of interventions? Attitudes toward female circumcision among people in the Hargeisa district’ (2013) 6 BMC Research Notes 122.

-

2 See UNICEF ‘UNICEF and UNFPA call on the government of Somalia to commit to ending FGM by passing law prohibiting the practice’ 6 February 2021, https://www.unicef.org/somalia/press-releases/unicef-and-unfpa-call-government-somalia-commit-ending-fgm-passing-law-prohibiting (accessed

23 December 2024); RK Moody ‘Women human rights defender’s fight against female genital mutilation and child marriages in Africa’ (2020) Africa, Cities and Health, Special Issue: COVID-19 2; BD Williams-Breault ‘Eradicating female genital mutilation/cutting: Human rights-based approaches of legislation, education, and community empowerment’ (2018) 20 Health and Human Rights Journal 226; TD Smith and others ‘Female genital mutilation: Current practices and perceptions in Somaliland’ (2016) 17 Global Journal of Health Education and Promotion 42. -

3 A Storey ‘Improving recommendations from the UN’s Universal Periodic Review: A case study on domestic abuse in the UK’ (2023) 35 Pace International Law Review 193.

-

4 World Health Organisation ‘Female genital mutilation’ 31 January 2023,

www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation (accessed 23 December 2024). -

5 As above.

-

6 ME Shember ‘Female genital mutilation and the First Amendment: An analysis of state FGM statutes and the right to free exercise’ (2019) 96 University of Detroit Mercy Law Review 431, 437.

-

7 United Nations ‘International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation’, https://www.un.org/en/observances/female-genital-mutilation-day (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

8 BBC News ‘Somalia country profile’ 2 January 2024, www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14094503 (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

9 28 Too Many ‘Somalia: The law and FGM’ July 2018 3, www.orchidproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/somalia_law_report_july_2018.pdf (accessed

23 December 2024). -

10 See BBC News (n 8).

-

11 28 Too Many (n 9).

-

12 See UNICEF (n 2); Williams-Breault (n 2); Moody (n 2); Smith and others (n 2).

-

13 Moody (n 2) 2.

-

14 28 Too Many (n 9) 1.

-

15 RA Powell & M Yussuf ‘Changes in FGM/C in Somaliland: Medical narrative driving shift in types of cutting’ vi, January 2018 Population

Council, https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?arti

cle=1534&context=departments_sbsr-rh (accessed 23 December 2024). -

16 Gele and others (n 1) 7.

-

17 CE Johnson-Agbakwu and others ‘Perceptions of obstetrical interventions and female genital cutting: Insights of men in a Somali refugee community’ (2020) 19 Ethnicity and Health 440-457.

-

18 UNICEF ‘Female genital mutilation’ June 2023, https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/female-genital-mutilation/ (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

19 UNICEF ‘Somalia’ (2021), www.unicef.org/media/128221/file/FGM-Somalia-

2021.pdf (accessed 23 December 2024); OO Awolola & NA Ilupeju ‘Female genital mutilation; culture, religion and medicalisation: Where do we direct our searchlights for its eradication’ (2019) 31 Tzu Chi Medical Journal 1-4. -

20 R Cassman ‘Fighting to make the cut: Female genital cutting studies within the context of cultural relativism’ (2007) 6 Northwestern Journal of Human Rights 128.

-

21 N Onsongo ‘Female genital cutting (FGC): Who defines whose culture as unethical?’ (2017) 10 International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 112.

-

22 Cassman (n 20) 128.

-

23 Gele and others (n 1).

-

24 N Mehriban and others ‘Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of female health care service providers on female genital mutilation in Somalia: A cross-sectional study’ (2023) 19 Women’s Health 8.

-

25 SR Hayford & J Trinitapoli ‘Religious differences in female genital cutting: A case study from Burkina Faso’ (2011) 50 Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion

252-271. -

26 Onsongo (n 21) 107.

-

27 WHO (n 4).

-

28 Smith and others (n 2) 45.

-

29 As above.

-

30 Gele and others (n 1). See also the adverse effects of FGM experienced by Kaafiyo Abdi Farah: UN Women Africa ‘From knowledge to action: Ending female genital mutilation in Somalia’ 31 May 2022, https://africa.unwomen.org/en/stories/news/2022/05/from-knowledge-to-action-ending-female-genital-mutilation-in-somalia (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

31 WHO (n 4).

-

32 See WHO ‘Female genital mutilation: A joint WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA statement’ 1997, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/41903/9241561866.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

33 Art 9(1) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1976) 999 UNTS 171 (ICCPR).

-

34 Art 7 ICCPR; Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, UNGA Res 39/46, 10 December 1984.

-

35 Art 122 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1978) 993 UNTS 3 (ICESCR).

-

36 See https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?

CountryID=107&Lang=EN (accessed 23 December 2024). -

37 Art 24(3) Convention on the Rights of the Child UNGA Res 44/25, 20 November 1989 (CRC).

-

38 At the date of writing, the United States of America is the only UN member state not to have ratified CRC.

-

39 Art 16 CRC.

-

40 Art 2 CRC.

-

41 Art 19 CRC.

-

42 Arts 1 & 2 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women UNGA Res 34/180, 18 December 1979, UN Doc A/RES/34/180 (CEDAW); UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women General Recommendation 14: Female circumcision (1990) UN Doc A/45/38 and Corrigendum; UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women General Recommendation 19: Violence against women (1992) UN Doc A/47/38; UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women General Recommendation 24: Article 12 of the Convention (women and health) (1999) UN Doc A/54/38/Rev.1.

-

43 Williams-Breault (n 2) 227.

-

44 Joint General Recommendation 31 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women/General Comment 18 of the Committee on the Rights of the Child (2019) on harmful practices (8 May 2019) CEDAW/C/GC/31/Rev.1–CRC/C/GC/18/Rev.1.

-

45 WHO (n 32).

-

46 UN General Assembly ‘Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilation’ 5 March 2013 UN Doc A/RES/67/146.

-

47 See https://achpr.au.int/en/charter/african-charter-human-and-peoples-rights (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

48 Solidarity for African Women’s Rights ‘Protocol watch’ 8 June 2023, https://soawr.org/protocol-watch/ (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

49 African Charter (n 47).

-

50 African Union ‘African Union Initiative on Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation Programme and Plan of Action 2019-2023’ (2022) 4-5, <https://au.int/sites/default/files/newsevents/workingdocuments/41106-wd-Saleema_Initiative_Programme_and_Plan_of_Action-ENGLISH.pdf (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

51 Plan International ‘Girls in Somalia subjected to door to door FGM’ 18 May 2020, https://plan-international.org/news/2020/05/18/girls-in-somalia-subjected-to-door-to-door-fgm/ (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

52 See AE Kouroutakis ‘The Constitution of Somalia on paper and the constitutional reality’ in Pedone (ed) Constitutions et lois fondamentales arabes ((2018), who also provides a clear overview of the situation in Somalia since its independence from British and Italian colonisation.

-

53 Art 5(4) Federal Republic of Somalia Provisional Constitution (adopted 1 August 2012).

-

54 Art 440 Somali Penal Code.

-

55 Art 29 Provisional Constitution (n 53); Somaliland Child Rights Protection Act (2022).

-

56 United Nations Human Rights Council ‘Summary of stakeholders’ submissions on Somalia’ (26 February 2021) A/HRC/WG.6/38/SOM/3 para 16.

-

57 UN Sustainable Development ‘Goal 5’, https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5 (accessed 23 December 2024); WHO (n 4).

-

58 UN (n 8).

-

59 C Adigüzel and others ‘The female genital mutilation/cutting experience in Somali women: Their wishes, knowledge and attitude’ (2019) 84 Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 118.

-

60 UNICEF (n 22).

-

61 Williams-Breault (n 2) 228.

-

62 As above.

-

63 S Nabaneh & AS Muula ‘Female genital mutilation/cutting in Africa: A complex legal and ethical landscape’ (2019) 145 International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 253.

-

64 WHO (n 4).

-

65 Nabaneh & Muula (n 63) 255.

-

66 Powell & Yussuf (n 17).

-

67 O Ogunsiji & J Usher ‘Beyond illegality: Primary healthcare providers’ perspectives on elimination of female genital mutilation/cutting’ (2021) 30 Journal of Clinical Nursing 9-10.

-

68 See the UPR Project at BCU ‘Joint submission of the BCU Centre for Human Rights and Arizona State University: Chad’ July 2023, https://bcuassets.blob.core.windows.net/docs/chad-stakeholder-report-upr-project-at-bcu-and-asu-133341461393814582.pdf (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

69 T Kachika ‘Juxtaposing emerging community laws and international human rights jurisprudence on the protection of women and girls from harmful practices in Malawi’ (2023) 23 African Human Rights Law Journal 126-155.

-

70 N Varol and others ‘The role of men in abandonment of female genital mutilation: A systematic review’ (2015) 15 BMC Public Health 1034.husbands, community and religious leaders may play a pivotal part in the continuation of female genital mutilation (FGM

-

71 As above.

-

72 As above.

-

73 As above.

-

74 Gele and others (n 1) 3.

-

75 Gele and others (n 1) 9.

-

76 As above.

-

77 Nabaneh & Muula (n 63) 256.

-

78 Gele and others (n 1) 9.

-

79 Williams-Breault (n 2) 230.

-

80 African Women’s Organisation, www.support-africanwomen.org/en/ (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

81 UN Human Rights Council Resolution 5/1 (2008) para 1.

-

82 UN Human Rights Council Resolution (n 81) para 3(m).

-

83 R Smith ‘A review of African states in the first cycle of the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review’ (2014) 14 African Human Rights Law Journal 363.

-

84 D Etone ‘African states: Themes emerging from the Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review’ (2018) 62 Journal of African Law 208, 223.

-

85 D Etone ‘Theoretical challenges to understanding the potential impact of the Universal Periodic Review mechanism: Revisiting theoretical approaches to state human rights compliance’ (2019) 18 Journal of Human Rights 36-56.

-

86 K Gilmore and others ‘The Universal Periodic Review: A platform for dialogue, accountability, and change on sexual and reproductive health and rights’ (2015) 17 Health and Human Rights Journal 167, 168.

-

87 G Patel ‘How universal Is the United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review: An examination of the discussions held on female genital mutilation in the first cycle of review’ (2017) 12 Intercultural Human Rights Law Review 187, 221.

-

88 Gilmore and others (n 86) 174.

-

89 Storey (n 3).

-

90 As above.

-

91 See OHCHR ‘Universal Periodic Review (Fourth Cycle): Information and guidelines for relevant stakeholders’ written submissions’ 3 March 2022, www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/StakeholdersTechnicalGuidelines4thCycle_EN.pdf (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

92 D Etone ‘The Universal Periodic Review and transitional justice’ in D Etone, A Nazir & A Storey (eds) Human rights and the UN Universal Periodic Review mechanism: A research companion (2024) 147.

-

93 E McMahon and others ‘The Universal Periodic Review. Do civil society organisation-suggested recommendations matter?’ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (2013) 1.

-

94 Etone (n 92).

-

95 While this research has aimed to include all relevant member state and CSO recommendations, there is a caveat that I have not included indirect references to FGM, only explicit references.

-

96 UNHRC ‘Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review: Somalia’ 11 July 2011 UN Doc A/HRC/18/6, para 98.27 (Report of the Working Group Cycle One).

-

97 Coalition for Grassroots Women Organisations (COGWO) Iniskoy Peace and Democracy, JS1 – Somaliland’s Civil Society Stakeholders’ Coalition, Kaalo, Peace and Human Rights Network (PHRN), Somali Family Services (SFS), and Save Somali Women and Children.

-

98 UNHRC ‘Contributions for the summary of stakeholder’s information – JS1’ 5, www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/upr/uprso-stakeholders-info-s11 (accessed 23 Dec-

ember 2024). -

99 Four recommendations also engaged with the broad theme of ‘gender-based violence’.

-

100 Report of the Working Group Cycle One (n 96) Italy (para 98.21); Norway (para 98.22); Canada (para 98.23); The Netherlands (para 98.24); Portugal (para 98.25); Australia (para 98.26); Islamic Republic of Iran (para 98.27); and Costa Rica (para 98.29).

-

101 Report of the Working Group Cycle One (n 96) Japan (para 98.60); Argentina (para 98.80); and Belgium (para 98.28).

-

102 Report of the Working Group Cycle One (n 96) Uruguay (para 98.55) and Spain (para 98.56).

-

103 Report of the Working Group Cycle One (n 96) Canada (para 98.81) and Mexico (para 98.82).

-

104 OHCHR (n 91) para 15.

-

105 OHCHR (n 91) para 11.

-

106 Somaliland National Human Rights Commission, Muslims for Progressive Values (MPV), Terre Des Femmes, JS4 – Somaliland Civil Society Organisations, JS5 – Somalia Civil Society Organisations.

-

107 See SLNHRC 4, MPV 10, JS5 4, and TDF para 12 available at UNHRC ‘Contributions for the summary of stakeholders’ information’, www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/upr/uprso-stakeholders-info-s24 (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

108 TDF (n 107) para 13.

-

109 MPV (n 107) para 9.

-

110 MPV (n 107) para 10; TDF (n 107) para 15.

-

111 TDF (n 107) paras 14, 15.

-

112 JS4 (n 107) para XI.8; JS5 5.

-

113 Nine recommendations also engaged with the broad theme of ‘gender-based violence’.

-

114 UNHRC ‘Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review: Somalia’ 13 April 2016 UN Doc A/HRC/32/12, Philippines (para 136.78); Norway (para 136.79); Australia (para 136.80); Belgium (para 136.81); Uruguay (para 136.82); Italy (para 136.83); and Canada (para 136.84) (Report of the Working Group Cycle Two).

-

115 Report of the Working Group Cycle Two (n 114) Japan (para 136.74); Spain (para 136.75); and Slovenia (para 136.119).

-

116 Report of the Working Group Cycle Two (n 114) Republic of Korea (para 136.76).

-

117 See Egypt-Peace The International Alliance for Peace and Development, SOS Children’s Villages Somalia, Joint Submission 3 – East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Project, NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC and National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders – Somalia, Joint Submission 6 – 13 Somali CSOs, JS7 – 126 Somali Civil Society Organisations, JS8 – Women’s Rights and Gender Cluster, JS9 – Somali Women Development Centre (SWDC) & Sexual Rights Initiative (SRI) UNHRC ‘Contributions for the summary of stakeholders’ information’, www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/upr/uprso-stakeholders-info-s38 (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

118 JS7 (n 117) Cycle Three 5; JS8 Annex 1 Cycle Three 31.

-

119 IADP (n 117) Cycle Three 7.

-

120 UNHRC ‘Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review: Somalia’ (11 July 2011) UN Doc A/HRC/18/6, Sudan (para 132.195); Sweden (para 132.196); Togo (para 132.197); Burkina Faso (para 132.199); Chile (para 132.200); Finland (para 132.204); and Canada (para 132.236) (Report of the Working Group Cycle Three).

-

121 Report of the Working Group Cycle Three (n 120) Zambia (para 132.198); Côte d’Ivoire (para 132.201); France (para 132.205); Greece (para 132.207); Italy (para 132.211); Latvia (para 132.212); and Liechtenstein (para 132.215).

-

122 Report of the Working Group Cycle Three (n 120) Japan (para 132.193); Poland (para 132.194); Norway (para 132.220); and Portugal (para 132.222).

-

123 Report of the Working Group Cycle Three (n 120) Croatia (para 132.192).

-

124 MPV (n 107) 10.

-

125 TDF (n 107) para 14.

-

126 UPR Info ‘Pre-sessions’, www.upr-info.org/en/upr-process/pre-sessions (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

127 The UPR Project at BCU ‘Namibia’ Centre for Human Rights, www.bcu.ac.uk/law/research/centre-for-human-rights/consultancy/upr-project-at-bcu/upr-project-at-bcu-namibia (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

128 UNHRC ‘Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review – Namibia (29 June 2021) UN Doc A/HRC/48/4 para 138.92 ‘Increase its efforts to tackle stigmatisation of and discrimination against persons, especially women and girls infected with HIV/AIDS, by prioritising support and education’ (South Africa); para 138.200 ‘Intensify its efforts to combat HIV/AIDS and prevent mother-to-child transmission’ (Thailand); para 138.205 ‘Step up efforts to end stigmatisation and discrimination against women and children infected with HIV/AIDS (Kenya).

-

129 A Nazir, A Storey & J Yorke ‘The Universal Periodic Review as utopia’ in Etone and others (n 92) 35.

-

130 As above.

-

131 See Storey (n 3); A Nazir ‘The Universal Periodic Review and the death penalty:

A case study of Pakistan’ (2020) 4 RSIL Law Review 126, 153; A Storey ‘Challenges and opportunities for the UN Universal Periodic Review: A case study on capital punishment in the USA’ (2021) 90 UMKC Law Review 148-149; E Hickey ‘The UN’s Universal Periodic Review: Is it adding value and improving the human rights situation on the ground?’ (2013) 7 International Constitutional Law Journal 1; C de la Vega & TN Lewis ‘Peer review in the mix: How the UPR transforms human rights discourse’ in M Cherif Bassiouni & WA Schabas (eds) New challenges for the UN human rights machinery: What future for the UN treaty body system and the Human Rights Council procedures? (2011) 381; R Chauville ‘The Universal Periodic Review’s first cycle: Successes and failures’ in H Charlesworth & E Larking (eds) Human rights and Universal Periodic Review: Rituals and ritualism (2015) 97; Centre for Economic and Social Rights ‘The Universal Periodic Review: A skewed agenda? Trends analysis of the UPR’s coverage of economic, social and cultural rights’ (2016), www.cesr.org/sites/default/files/CESR_ScPo_UPR_FINAL.pdf (accessed 23 December 2024); S Shah & S Sivakumaran ‘The use of international human rights law in the Universal Periodic Review’ (2021) 21 Human Rights Law Review 264, 275; W Kälin ‘Ritual and ritualism at the Universal Periodic Review: A preliminary appraisal’ in H Charlesworth & E Larking (eds) Human rights and Universal Periodic Review: Rituals and ritualism (2015) 35-36. -

132 UPR Info ‘A guide for recommending states at the UPR’ (2015), www.upr-info.org/sites/default/files/general-document/pdf/upr_info_guide_for_recommending_states_2015.pdf (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

133 A Storey & M Oleschuk ‘Empowering civil society organisations at the UPR’ (2024), https://bcuassets.blob.core.windows.net/docs/empowering-csos-at-the-upr-full-report-133680282970363754.pdf (accessed 23 December 2024).

-

134 Report of the Working Group Cycle One (n 96) para 98.23.

-

135 JS7 (n 117) para 5.

-

136 JS7 (n 117) para 10.

-

137 See J Baumgardner ‘A multi-level, integrated approach to ending female genital mutilation/cutting in Indonesia’ (2015) 1 Journal of Global Justice and Public Policy 267.

-

138 JS7 (n 117) para 12.

-

139 JS7 (n 117) para13.

-

140 IADP (n 117) para 7.

-

141 Report of the Working Group Cycle Three (n 120) para 132.194.

-

142 Storey (n 3).

-

143 Yemo also found that an intersectional approach to stakeholder reports would be of benefit in her study on recommendations made to Sudan on women’s rights generally. See R Yemo ‘Intersectionality and the Universal Periodic Review: A case study of Sudan’s women’s rights recommendations’ (2023) Women’s Studies International Forum 98.

-

144 JS7 (n 117) para 4.

-

145 JS7 (n 117) para 5.

-

146 The Republic of Somalia ‘The consideration by the government of Somalia of the 155 Recommendations (Long Version) (21 September 2011) SPR/UNOG/000431/11.

-

147 Report of the Working Group Cycle Two (n 114) para 136.82.

-

148 UNHRC ‘Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Addendum: Somalia’ (7 June 2016) UN Doc A/HRC/32/12/Add.1 5.

-

149 See part 2.4 on ‘Strategies for eradicating FGM’.

-

150 Storey (n 3).

-

151 Eg, the BCU Centre for Human Rights provided support during Sudan’s cycle two pre-session, after some Sudanese CSOs were prevented from leaving the country to attend the pre-session in Geneva; see the UPR Project at BCU ‘Sudan’ Centre for Human Rights, www.bcu.ac.uk/law/research/centre-for-human-rights

/consultancy/upr-project-at-bcu/upr-project-at-bcu-sudan (accessed 23 Decem-ber 2024); Storey & Oleschuk (n 133).